Category — Features

The Naturalist

“I grow delicious fruit and then I try to preserve it as simply as possible with fermentation – it’s an age-old ritual.”

Lance Redgwell of Cambridge Road Vineyard refers to himself as a wine-grower and suffers no dogma, his wines are an “evolving storyline”.

His flagship wine is a blend of pinot noir and syrah from his ‘home block’, but because that’s not pushing the boundaries quite enough, he’s also embraced the natural wine movement (in its infancy in New Zealand) and is hand-crafting a fascinating selection of exciting, affordable organic wines. His presentation in a Champagne bottle topped with a cap more commonly seen on a beer bottle is perhaps the perfect emblem of his Hi-Low ethos.

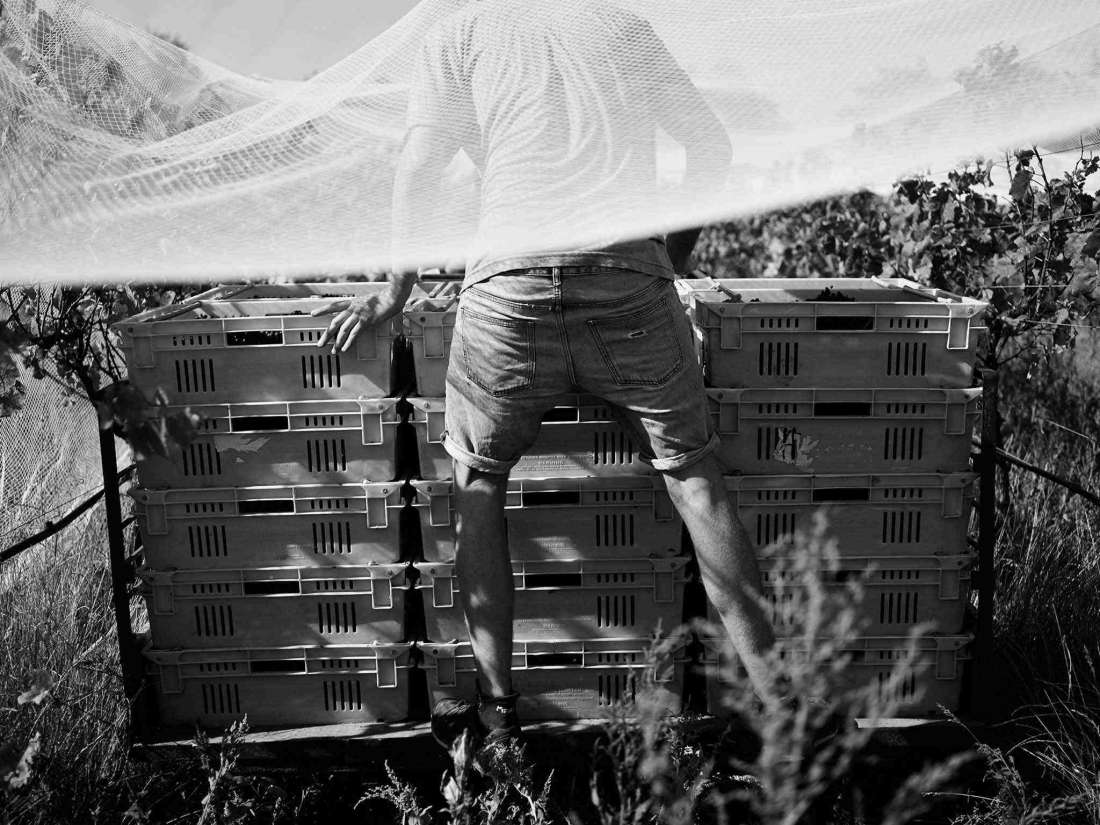

Autumn is a busy time in a vineyard, with the harvesting of the vines’ abundance and preserving it to provide us with an elixir to help us through winter. I was fortunate enough to tag along with Lance, his friend’s dog Chester and his team of WWOOFers this vintage to pick and stomp grapes in Martinborough and have the chat that I’ve presented with minimum intervention below.

SSS – If your winery were a band, which would it be?

The first that comes to mind is Stone Temple Pilots, for some strange reason – just a little bit wild and out of control. We like to think outside the square, I think, there’s certainly a bit of punk attitude, particularly the natural work… maybe that’s not the correct connection, there is this core that’s a little more traditional than that. I probably should have picked somebody that was more classically trained and then went off the rails.

SSS – It sounds like you had a journey leading to Cambridge Road, sailing and boat building as well as winemaking. Did you take off in pursuit of wine knowledge to bring home or did it find you on your travels?

I went to Europe in search of cultural knowledge, as much as anything, to get a perspective on culture through the way they share food and beverage. So I went looking for wine knowledge, but found myself very content gardening in Italy, living in a small village and eating great ham and cheese and olives and chocolate. It’s an endless journey – for me wine is only a part of the culinary formula or experience, it’s all about eating or embracing the flavours of life.

SSS – Why Martinborough?

I travelled the whole country considering all alternatives with the prospect of starting a farm and could have been very happy in a variety of places. Martinborough… right time, right place, great climate, it’s North Island based, which suits my family, and it’s the best part of the North Island for cool-climate viticulture. Plus it’s the cutest little wine village in the country hands down, the scale of agriculture here, everything’s very neighbourly, everything’s… it’s intimate, in a way – you stroll from vineyard to vineyard. And it’s got bloody classical roots and I’ve got a lot of respect for those things, for the pioneers of the region, Ata Rangi, Dry River, Martinborough Vineyards and the like, they’d proven the potential. Arguably I know of no other region in New Zealand that achieves so highly across such a diverse portfolio of wine styles and varieties. So that opens up a lot of opportunity for exploration. I felt pretty lucky to get a foot in the door of the potential that is Martinborough.

SSS – So the pioneers had done the groundwork in terms of solidifying a reputation for the region and that gives you the freedom to have a bit more of a play?

Exactly. As the second generation of New Zealand wine-growers, the old guard are still very much running and driving the great companies of New Zealand, but there’s this energetic freshness and slightly more edgy… well, different perspective on what great wine is, how we can achieve that. And we’re carrying with us a bit more confidence, perhaps – that’s where it resonates back to the guys who pioneered wine here and throughout New Zealand, who put the hard yards in and established the reputation of quality. They’ve given us the opportunity and the confidence to pursue more, I don’t know… dynamic philosophies, to push the boundaries out a little bit further, explore new territory, that sort of thing. So it’s kind of nice to be part of that group.

SSS – Your flagship wine, Dovetail, is a blend of syrah and pinot noir. Am I right in understanding the mix matches the proportions of the varieties grown on the property?

As of today you’re correct, but I don’t like to be constricted by any formula. The first Dovetail kicked of in ’08 – it was our second vintage and was not blended in those ratios, that was a blend based on the best-tasting red wine I could make from ‘home vineyard’ and was more like 60 per cent syrah and 40 per cent pinot. There were a couple of delicious variations but that was what we ultimately went to bottle with. There’s this absolutely instinctual nature that comes with being both the grower and the winemaker. You get a feeling for what the vineyard is speaking of. Some years are particularly suited for pinot noir in Martinborough – I like the cooler vintages, personally – and in the really hot years syrah starts to sing at full voice. In the end I don’t profess to be wiser than the land itself… it is what it is and we don’t know until we get pretty close to the finish line just how good that can be. We’ve got an inkling as to the potential of our crop and of the wines we’ve made, but until you get really close to that final signing of the canvas everything is fluid, nothing is set in stone. Wines need to have a seamlessness, a calm elegance about them that you can’t force, it’s either there or it’s not, and when it comes to blending, things either fit or they don’t, that’s why I shudder to say Dovetail is always a blend in the proportions of home vineyard. It happened to be the case in 2010 and 2011 because it worked beautifully, in 2013 there was no Dovetail, in 2014 my home blend was back to syrah dominance – so some years it works beautifully and some years it doesn’t.

SSS – Is syrah and pinot a common blend? I don’t think I’d ever heard of that before hearing about Dovetail.

Yeah, it’s a real rarity. It’s rare to find the grapes in the same region because they tend to come from different climatic environments. Martinborough sits on this ley line of sorts, I believe – a meeting of two climatic bands. We’re cool enough to do elegant pinot noir yet we’re just warm enough to achieve super-elegant syrah. So the fact that the two share the same soil on a very small parcel of land, they’re the same age – approaching their 30th year – they have the same farmer looking after them in all of his… you know, we talked about cow preparations and sprays and things [Lance uses the local seaweed to make organic and biodynamic sprays], they share the same minerals in this earth. That whole Dovetail idea, it’s certainly the most unique thing that we make. There are very few… one or two unproclaimed blends in New Zealand and about half a dozen globally that I’ve discovered so far.

We’re looking at this beautiful, elegant, cool-climate charm that you associate with pinot noir, the charcuterie and the sort of… wild side, with a little bit of mushroom, foresty, funky characters, but then we’re feathering that with syrah, which in our Martinborough climate is very elegant, lovely acidity, beautiful spices running from pepper to anise, bits of liquorice running through, and the fruit is a little bit blacker, it’s like blackcurrant, like sour little black fruits, like just-ripe blackberry, and then this charming little floral botanic spectrum as well. So we’re just playing with more threads, in a way. I’ve got, as a builder… as a chef, as a maker of flavour, I have the opportunity to work with more components to make a more complex and interesting and unique flavour. And that’s what Dovetail is about, it’s about trying to share something that is unique, not just another pinot noir. It’s something to discover, it’s not only unique the first time you open it, it’s intriguing every time you pull the cork and I love the idea of discovery.

SSS – So the minimum intervention, natural inputs approach to viticulture, is that inspired by an environmental ethos towards the land or is it solely about the flavour that’s imparted in the grapes?

It’s fundamentally environmental. Not just towards the land but the environment in general. We look at carbon inputs, we look at energy efficiency, we look at treading gently. I wanted to create an environment in which my family can thrive, a place where children can play with no fear of poisons, a place where life surrounds us.

Flavour, quality and nourishment is what pushes me the extra mile, it’s the reason we collect seaweed or get out of bed at dawn to stir preparations for the land.

SSS – What is “natural wine”? Did you bring that interest back from your travels abroad or has it emerged as a by-product of your winemaking process?

Natural wine… that’s a big question that people are trying to fingerprint right now, because it’s generally based around freedom of expression, so once you start to lay rules into that kind of ideology you defeat its foundation or its founding philosophies. The way I feel about it may be different to how others feel about it. To me it’s fundamentally based on organic fruit, it’s certainly about zero additives in the winery, no artificial additives whatsoever. It’s wine made from grapes. Only.

Wine doesn’t have huge amounts of anything but grapes, but there are lots of things added in tiny amounts in commercial winemaking that the purists, the naturalists… whatever you want to call them, choose to avoid. I take a rational philosophy to the movement and a certain batch of wine might need a degree of intervention in the form of sulphites, which is the big buzzword in the movement, simply because they’re an allergen, they’re labelled and we can make wines without them. The objective to make wines without sulphites struck a personal chord with me, both my mother and my brother have a mild allergy – I might have even had one too – and I’ve been able to make wines in a good year with good fruit that are compelling and interesting and delicious without the need for anything. But on a bad year and you’ve got mould starting on your fruit, for example, it would be incredibly risky to make those kinds of wines and expect them to taste delicious. Natural wine also generally excludes the use of filtration as well and obviously any of the fining agents – gelatine, albumin from egg whites, fish proteins, nowadays there are vegetarian fining agents like pea-based proteins, they’re not evil creatures.

SSS – So if they’re not evil things, is it a little bit about not being in control? Is that part of the fun, by surrendering these tools you get to play a different game?

Handing off some of the control to the forces of nature, in a way, but to say we throw away control is incorrect, we still have control of the choices we make in terms of temperature, fermentation vessels etc etc… it’s not something that you do without a knowledge of the laws of nature or the laws of natural fermentation science. There’s a bunch of us who’re trying to push the boundaries to see just how little we can do to something, how pure something can be, how honest it can be.

One of the people who I most admire in the industry is a guy called James Millton from Millton Winery in Gisborne, and he’s been growing organic grapes forever, since the 80s, pretty much since he started, and he was ostracised for his choices – like he had to put up with decades of being a weirdo to do what he believed in – and now there’s been a renaissance or a certain coolness that’s been attributed to this style of winemaking and it’s now accepted globally as a way to make great wine. James makes a bunch of great wines, he does filter some of them and he does sulphur some of them, but his wines are fuckin’ stunning and I’d happily serve them to anyone.

SSS – And not talking about “natural” wine any more but about James and your attitude towards the land, it’s obviously proving to express itself well in the bottle. Treating your land well makes the wine taste nice, is that the deal?

Sure, treat your land well, it’s a simple act. We grow the best damn fruit we can, we put a lot of TLC into it, we manicure it like any living plant. If you want to grow good basil or tomatoes at home you take care, right, and you can tell when it’s delicious and perfect and if you make that caprese salad you can tell the difference, you can tell when a tomato’s a fuckin’ delicious tomato and you treat it simply and let it be. And as a winemaker that’s what I try to do. I grow delicious fruit and then I try to preserve it as simply as possible with fermentation – it’s an age-old ritual, it’s millennia old and we observe this simple process. It’s about accepting imperfections as well, embracing what are classically termed as slight faults. A little bit of imperfection makes it all the more real and all the more true and to me all the more delicious.

SSS – It seems like there are two streams here. There’s organics, look after the land, which is an attitude that you could have even if you were making really classical wines, and then there’s let’s be creative and have a bit of a play.

Everything’s creative, all of us as winemakers are in it to be creative. At my core I have a really classical training and a classical line of wines – with minimal intervention – and then I have my looser stuff at the fringes, which is more the abstract art. And I enjoy the crossover of those two worlds – it’s about shifting the bell curve in the direction of less. Less is more. And we use fun, affordable and experimental pieces in small volumes that we test theories on and when we’re confident in those theories we can apply them to more of the mainstream wines that we make. And that’s a really interesting journey to be on, it keeps life interesting, it’s about evolution in terms of thinking, technique and also flavour. I think one of the things that’s exciting about it is for a bunch of people out there who’ve tasted a lot of wines, these are different. It’s like any sort of art or cultural movement, in terms of food, art, architecture or design, we like to be shocked occasionally, and challenged.

SSS – And you bottle wine when it’s got some fermentation still to take place?

That’s simply a technique I utilise to deliver wines that still have that fresh fruitfulness, like the Cloudwalker, which is bottled while it’s still got a little bit of fermentation to undertake. As you exclude additives you need to look to what’s available naturally in terms of preservatives, and you’ve got two paths to take, or you can combine them. You’ve got tannic extraction – through whole-bunch fermentations on the stem you increase your tannic load, which has an antioxidant effect that’s going to prevent oxidation to a large degree; the wines become more robust in every way, they can handle air exposure quite well. And the other way is through dissolved carbon dioxide, and this is where the bottle-fermented products come into play. The yeasts chew up all the oxygen that it was bottled with – there’s no more chance of oxidation, unlike leaving it in a barrel for a year or three, there’s very little chance for spoilage to take place. You’re preserving it naturally and by bottling young while it’s still fresh and fruity you basically create a time capsule.

SSS – The movement is taking place in winemaking, but is it happening with your audience? Are Kiwis becoming more intrigued by these wines?

Slowly. We’re at the tip of the needle with New Zealand’s understanding of these styles. What’s great is that I have the cellar door and we educate a lot of people. When I get to explain the wines to the public that consumes them they get it, they love it. Other markets globally are further along, they’ve been exposed to these wine styles for longer. The movement is driven by historical producers in Europe that’ve always made wines with this ethos.

SSS – Because it’s kind of going back to go forward, it’s not like you’ve reinvented the wheel, you’re looking back at ways wine was originally made.

Yeah, we’re looking at archaic wine, in a way. There are some really interesting perspectives coming out of Georgia on the Black Sea, which is the historical foundation of civilised wine production. That’s where the ancient artefacts of wine exist, 4000-year-old history, and that’s driving a resurgence of interest in terracotta and amphora fermentation. There are guys there who’ve been making wine the same way as it’s been made for thousands of years, guys who’ve never stepped away from that. Some of the wines are challenging but they’re very authentic to the culture and the heritage of the place and the foods that go with them.

SSS – I saw on Instagram you were raiding roadside apple trees to make a quick batch of cider before harvest kicked in. So you’re doing all this stuff in order to keep things fun but then you need a bit of extra excitement before the harvest starts.

There are a couple of reasons I wanted to embark on that. It’s to keep life interesting, the idea of making a friendly, sessionable low-alcohol lunchtime beverage that we can enjoy. It’s also about embracing the fact that harvest – the autumn season – is a long season, and part of the knowledge and philosophy that we apply to grapes can apply to other fruit such as apples and pears, it’s just common sense. It extends our harvest and allows us to enjoy more of what surrounds us. And I like the idea of lower-alcohol alternatives, I’m really happy to spritz my wines as well, for lighter enjoyment. All of my wines, but particularly the ones that’ve had a bit more skin contact, have a depth of flavour that if you cut them 50/50 with sparkling water, you’ve got yourself a delicious lunchtime beverage, and you can buy that $30 bottle and turn it into two bottles, which is great if you’re sitting down to lunch with family… and you can go back to work. I think New Zealand as a culture needs to embrace the spritzer movement a lot more. Europeans have been doing it for years, it’s just responsible lunchtime enjoyment.

Interview and photography: Aaron McLean