Category — Features

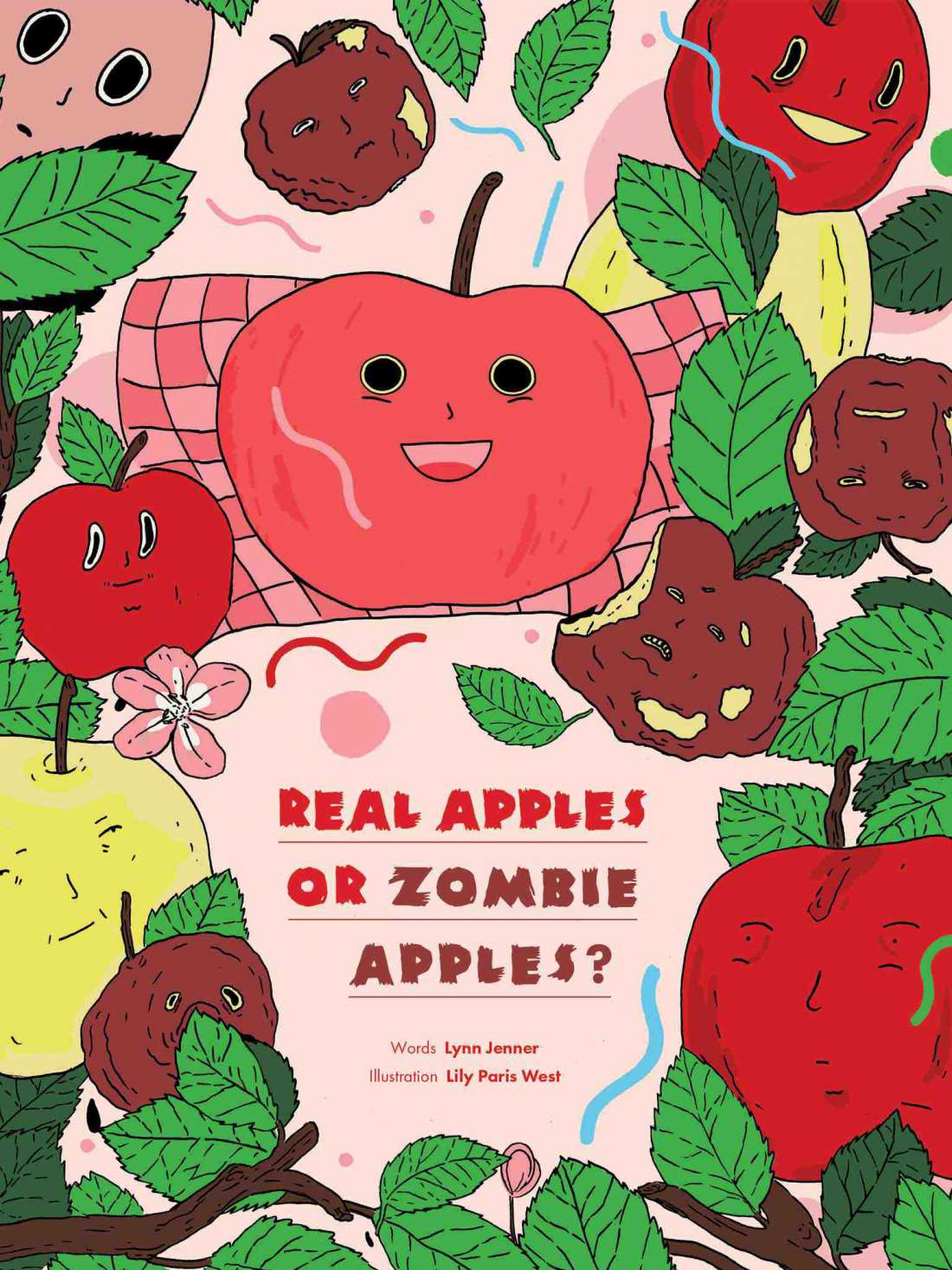

Real Apples or Zombie Apples

In the last few years I’ve given up buying apples from the supermarket because I’ve finally realised they are zombie apples. It’s fairly easy to tell if you have bought a zombie apple.

It will:

– have no crunch,

– seem when cold to be crisp, but as it warms up, it becomes floury,

– have no acid,

– have no taste,

– have tough skin.

So where have all the real apples gone?

When I spoke to a fruit producer about my apple problem, he looked at me as though I was hopelessly naïve, which is fair enough. Supermarkets are all about sales volume, he said. Supermarkets are highly competitive so they ‘need’ to set the price low to make sure customers are going to buy their apples. That means they ‘need’ to buy from producers at the lowest possible price. The growers know this, of course, so they breed apple varieties that produce fruit in bulk, not fruit for texture or flavour. Enter the zombie apple.

Back to us. Over the last 50-odd years we have ‘said’, with our buying behaviour, that we want to buy food once a week and all at the same place. We want everything, all year round. Including apples. And we want it all to be cheap. Now we have what we wished for, except it turns out to be terrible. So how could this cycle change?

I asked the fruit producer. He said consumers are more powerful than they might think. It is up to us, he said, to take our money and our dissatisfaction and find ways to buy apples that we like. OK. So how exactly do we do that?

We are lucky. The real apples have not died. The trees are still there, forgotten and abandoned in corners of old farms and gardens. And there are some people who fell out of love with mass food production years ago. They know what to do.

Enter the Open Orchard Project.

In Riverton, a town in coastal Southland, Robert and Robyn Guyton’s inspiring Open Orchard Project is bringing healthy old varieties of apples back from the brink and making them available for a new generation of gardeners and cooks. Robert is a major apple-fancier, or, as some people say, a ‘pomologist’. It was a real thrill to talk to Robert about apples, and that is what follows here, but before I start I want to make it clear that Robert is much more than a single-issue guy. His ideas about community building and permaculture pop up during our discussion. I’ll be talking to him more about his Food Forest and permaculture on another occasion.

I decided to start by asking Robert about the pleasure of a real apple, then get into the serious thinking and the work behind the fruit.

LJ: What is your favourite apple? What is your favourite way to eat or otherwise consume apples?

RG: My own favourite apple is one that’s becoming more and more popular as people get the chance to taste it. Mrs Peasgood found a sport (a spontaneous mutation, often a different colour from the parent type) of a well-known Nonsuch apple and dubbed it, not surprisingly, Peasgood Nonsuch, and since that day, people have marvelled at its size – enormous, and taste – exquisite when stewed. I like to eat half a stewed Peasgood Nonsuch apple for breakfast, spooned over my porridge. It’s sweet and creamy and well worth coveting.

LJ: Can you give us an apple recipe for around the month of May that you like?

RG: In May, the best of the late apples, such as Belle de Boskoop or Adams Pearmain, having been stored for several weeks, are at their most flavoursome. Bake with them – a flan or a tart perhaps – or cover them with a crumble and bake them in the oven. Nicer than nice.

LJ: Peasgood Nonsuch, Merton Russet, Norfolk Greening, Adam’s Pearmain and Warner’s King are just five of the 60 varieties mentioned on the 2015 Open Orchards Apple Varieties list. The names are like poetry. Why do they have such magical names?

RG: The names resonate with us, I believe, because they hark from an age when fruits were regarded with delight, rather than reluctant acceptance, as the modern, supermarket-purchased apples could be said to be. Mind you, there’s nothing especially magical about the name Catshead, one of the cider varieties. On the other hand, another cider apple, Slack Ma Girdle is pretty evocative and fairy-tale-ish. The name Kentish Fillbasket would fill anyone with hope and the many, many apples varieties that bear the names of kings and queens, emperors and empresses certainly add to the aura of mystique.

LJ: I read on your blog that the Open Orchard Project has been going for five years. What is the project and what is it trying to do?

RG: Robyn and I had been thinking for some time about the wonderful apples we’d seen on the hoary old trees in orchards all across Southland. We wanted to know about their names, their origins and their history since they arrived in New Zealand with the forebears of many of our long-established Southland families. We could see that many of the trees were on their last legs, if trees can be said to have legs, and wouldn’t be around for much longer unless someone stepped in and gave them a new lease of life. We decided to be that “someone” and learned to graft apple trees so that we had the necessary skills for the rescue operation. We began with an orchard near Riverton and haven’t stopped yet. We’ve managed to collect scions (cuttings for grafting or rooting) from almost every aged apple tree in the region and graft new examples of those treasures to replant back into those orchards, alongside roads, in purpose-made “neighbourhood orchards” and in numerous other places all over Southland. We had to have a name for what we were doing, and chose “Open Orchard” to express our confidence that being open and giving was the way to go about any project, and that in the same way that open-source software is a shared, self-improving system, so too would our project if it carried the same expression of openness. It’s proved to be the case and Open Orchard is thriving and has spread quickly from our own town, out onto the region then onto regions across New Zealand, where the title has been retained, though the varieties of apples are different.

LJ: You mention that you saw old orchards as you were driving around Southland. I can picture gnarly old trees, perhaps like some I have seen in old gold-mining parts of Central Otago. What made you notice the trees?

RG: The old apple trees caught our attention as we were visiting old farmhouses in search of materials to incorporate into the house we were building in Riverton. We were lucky enough to be gifted or sold cheaply items such as kauri doors, totara veranda posts, claw-footed iron baths, Bakelite light fittings and so on, by friendly Southland farmers who had no further use for those things and the old houses they sat in. It was while we were gathering up what would become features of the home we live in and raised our children in that we noticed the often overgrown and neglected orchards behind the farmhouses. The trees themselves seemed attractive in their many gnarled forms, but it was tasting their fruits that caused us to become passionate about halting their disappearance.

LJ: How did you get from noticing the trees to the idea of resurrecting the old varieties of apples?

One taste of an apple like Merton Russet, Bramley’s Seedling or Keswick Codlin is enough to convince anyone of the need to save the tree they are growing on from destruction, and that’s how it was for us. Robyn felt a strong desire also to conserve the stories of those particular trees and their connection to the families that ate them over the past decades, so she began to talk with the farmers about the history of the trees; who planted them, who picked, stored, cooked and ate them and even further back into the ancient history of the apple family, all the way to their roots in Kazakhstan, where they emerged as a wild fruiting tree.

LJ: How does the people side of the Open Orchard Project project work?

RG: All of the Open Orchard work is carried out by volunteers and they all love to be involved. While Robyn does the paperwork – recording varieties found, mapping the remnants of the farm orchards, comparing and identifying the apples and so on – others help with the physical work of collecting scions, grafting those onto rootstock, pruning the new trees as they grow, digging and lifting young trees for sale and relocating to the orchard parks we have created along with the district council. The numbers of volunteers involved in the Open Orchard project varies depending on the season and the work needing to be done. The annual Heritage Harvest Festival (held in late March/early April every year), which features the project and its apples, attracts dozens of helpers for just that weekend, and many other locals keep the project going throughout the year.

LJ: What is the vision for the Open Orchard Project in the future?

RG: The project keeps growing. Although we’ve collected and grown hundreds of examples from the old orchards of Southland, new ideas keep emerging, such as the creation of orchard parks near every town to showcase and preserve the trees of that particular area. Robyn’s newly published book, Open Orchard Handbook (available for $15 through the South Coast Environment Centre: sces.org.nz) is very popular and wherever it is sold, creates interest in further searches for heritage apples. The project has attracted the attention of overseas apple-fanciers, who call themselves “pomologists”, and they are very interested indeed in what we have found here in New Zealand, Southland in particular, and believe we have varieties here found nowhere else on the planet, thanks to our climate, history of apple growing and conservative natures. They are due to visit soon, such is their interest in seeing for themselves such rare varieties as the Yellow Ingestre, believed extinct everywhere but here.

LJ: You mention the preservation of skills as a part of the Open Orchard Project. What skills are people learning from being involved with these trees?

RG: Robyn and I teach anyone who wants to learn about pruning and grafting apple trees. As well as would-be-orchardist adults, we teach scores of school children the ancient art of fusing one apple variety to another. It’s not difficult, but it does need hands-on experience to create enabled enthusiasts. Robyn’s handbook covers everything else a grower would want to know about growing apples, along with a whole lot of interesting background information about the Open Orchard project and the history of apples.

LJ: The Open Orchard Project is based in Southland. Do you get interest from other parts of the country?

RG: There are “scions” of the Open Orchard project in many other parts of New Zealand, all progressing the saving of heritage apples in their own localised way. Many regions are less fortunate than Southland and have lost much of their apple history to progress, but we are sharing our good fortune with them, in the form of knowledge and scions from our own trees, posted out from the environment centre on request. Varieties can be viewed on the centre’s website, sces.org.nz.

LJ: Could there be an urban version of a project like this?

RG: Any urban group could do as we have done, searching the neighbourhood for old apple trees, pears and plums too, as well as peaches, apricots and plums; anything that’s traditionally grown in the area. All of the skills they need are easy to learn and equipment needed is minimal.

LJ: Can you say a bit about the South Coast Environment Society? For example, does the Open Orchard Project need a context like this to develop?

RG: The South Coast Environment Society is a progressive, friendly, helpful organisation that busies itself with a wide range of community-building projects. Their environment centre, on Riverton’s main street, is a marvellous place to visit and a source of much inspiration. Their website gives a very good idea of the projects they operate and the activities they promote.

Resources mentioned in the article or used as background:

Robert Guyton

South Coast Environment Society

Email – The Open Orchard Handbook

Illustration : @lilypariswest