Category — Hospitality/Dining

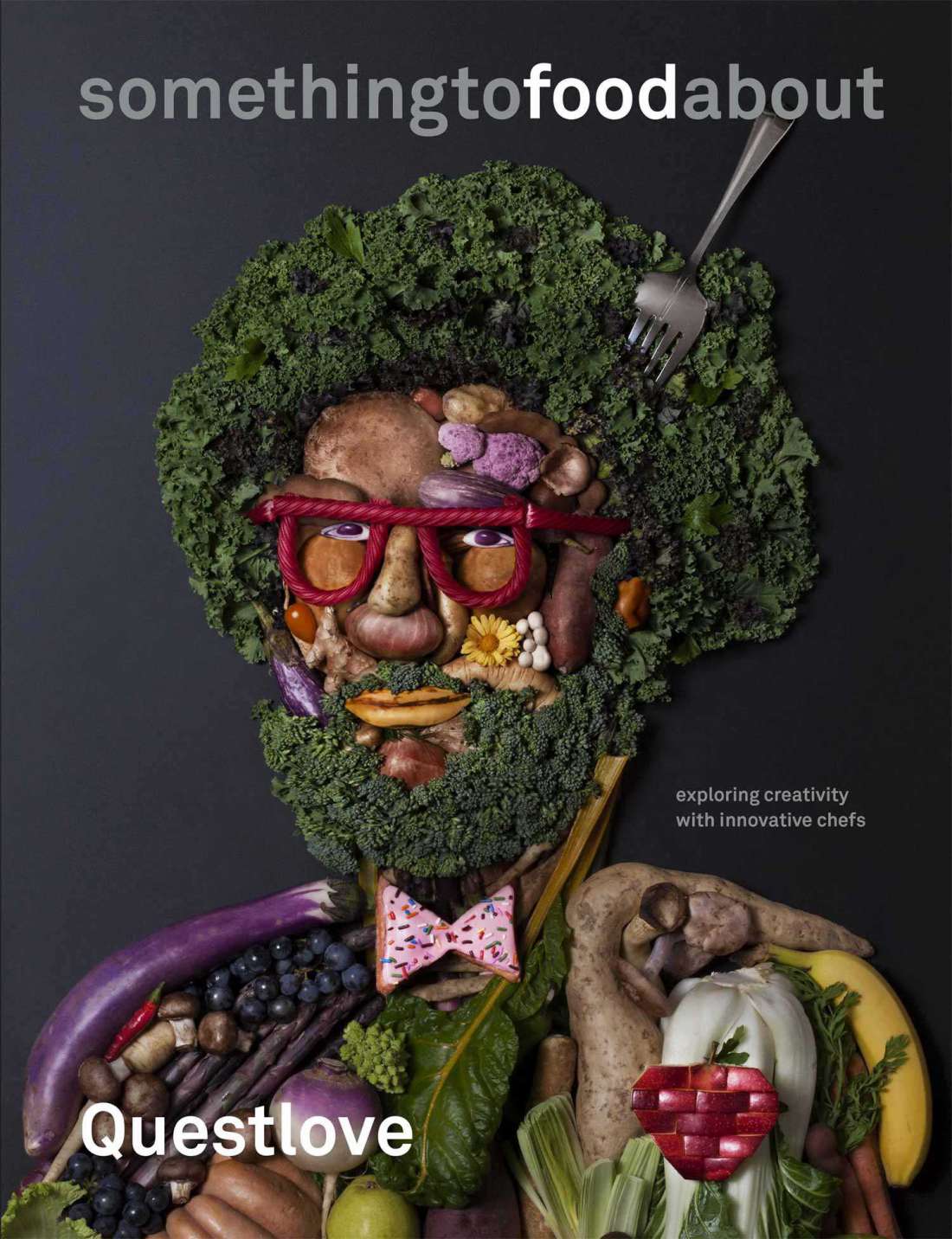

Questlove

“What is food for thought? Why does food for thought make you hungry? And hungrier, the more you eat? How is an idea translated into food? Are ideas something you can taste? I had endless questions about food, about cooking, about the science of cooking, about restaurants, about chefs. I had time to go in search of the answers. That’s where I’ve been. Here’s what I brought back from my journey…”

This book is about food in America, but it isn’t really about food, and it doesn’t start in America.

A few years ago, I went to Japan for my birthday. While I was there, I ate at Sukiyabashi Jiro. I had seen the documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, which is an inspirational biography of the famous sushi chef Jiro Ono, his quest for perfect sushi. I watched this film on repeat for months in awe of Jiro’s commitment to his craft. He inspired me. And at the same time, I could relate to him, or at least to the questions he was asking himself. What does that mean, to perfect sushi? Does perfect sushi even exist? I know the feeling, at least when it comes to music: you can go through a first take of a song, and a second take, and a fiftieth, and sometimes you feel like you have hit the sweet spot, and sometimes you feel like you’re moving further away. Is this drive for perfection necessary for creative people, or is it just something that happens to creative people whether it’s necessary or not? All I knew for sure was that Jiro was still dreaming of sushi, and I wanted to be in his dream if he would be in mine.

And so I went, into the Chuo ward, into the Ginza district, onto 4-chome street, and finally into the basement of the Tsukamoto Sogyo Building, a nondescript glass-and-steel office tower topped by the gaudy neon signs that are so common in downtown Tokyo. I am an obsessive documenter, and during my meal—which included a brief audience with Jiro himself—I started taking pictures and posting them to Instagram. It’s good that I did because while the food was impeccably prepared with flavors and textures I couldn’t have imagined, and it was also a sensory heaven in other ways, too: how it looked, in shape and color, how it smelled, how Jiro and his staff composed the meal like a piece of classical music.

If you’ve never been to Sukiyabashi Jiro, then you’ve never been to any place like Sukiyabashi Jiro. One of the dishes uses an octopus that has been massaged for hours. How many hours is enough when it comes to octopus massage? Only Jiro knows, and he feels that he needs to know more to be sure. That’s the spirit of the place, and the longer I sat there, soaking it in, the more I started to understand it. Is his obsession a kind of freedom, or a kind of imprisonment, or both?

The octopus was massaged for hours.

I am notorious for long-winded posts on Instagram, but something about Jiro got me really writing. I was excited and excitable, and something about the intensity of the place left me a little raw (no pun intended). Here’s one of the comments I posted:

I was like Popeye to spinach. ’Member when Michael Jackson tried that tonic in the “Say

Say Say” video and it made him dance? You don’t? Google it. I didn’t dance, but damn if I wasn’t in my head doing T.A.M.I. Show James Brown splits singing “Night Train” (Sting fans feel me . . . yes even my referenced references have footnote references).

To me, at that moment, food was more than food: it was words, and it was the memory of music, and it was the memory of old television shows, because really it was ideas married to the senses. That’s what those things are, too—they are my basis, in fact, for understanding how ideas could be married to senses, and where they would go for their honeymoon after.

My Instagram blew up. People couldn’t get enough of my comments about my food, even though they could no more taste it than I could jump through the screen and taste what they were eating—meatloaf in Miami, or pho in Phoenix. I know they were eating those things because when I got home from Japan, I walked back up the electronic trail, looked at the Instagram accounts and the blogs of the people who followed and reposted and commented on my Jiro pictures and writings. The world of food, of thinking about food in a nonprofessional, nonscholarly, but endlessly enthusiastic way, was larger than I thought. And the same way that endless enthusiasm had spurred me, at Jiro, to new heights, these people all over the Internet were writing and thinking about food with depth and intelligence and humor. They were going to restaurants in their hometowns and they were Jiro-ing them. They were making me dream and making me fans of these other chefs.

That experience planted the seed for this book. In my normal life, I travel all over. When I’m in other American cities, I stop to eat. I try to eat in places that move me as much as Sukiyabashi Jiro did. They don’t have the same history or the same philosophy. They don’t use the same ingredients. But there are restaurants in every city where the chefs are devoted to innovative, intense, idiosyncratically brilliant food. They prepare it, cook it, and present it as if it’s artwork, which it is. Not every restaurant is necessarily a place for innovation and vision, but those that are do what Jiro did: they put you in their dream.

As a musician, I have spent two decades traveling all around the country and the world, touring. When I was first on the road, I ate wherever was convenient. That’s a common behavior among musicians.

But at some point, I realized that my interest in food was something more involved and textured, and I started to ask the runners to recommend places— not necessarily the best in that businessman-intown way, but spots I had to try. I started to invite friends of mine to these restaurants, as sharing the excitement, the privilege, the experience of dining in a restaurant—whether it’s a date at White Castle on Valentine’s Day or a marathon sushi meal in Tokyo—sharing in the experience with people is what food, culture, music, and art is all about. When I am in other cities, I now make it a priority to visit innovative restaurants, and to think about what I’m seeing there. How is the food prepared? How is it served? Who is the chef? What are the ideas that circulate in the process?

I’m fascinated by chefs, people who have decided to devote their lives to food—to making it, but also to thinking about what it means to the broader culture. How does it make us who we are? How much is it a product of, or a producer of other parts of our culture? Or is it both, which means that it’s almost unimaginably complex? That fascination led directly to this book: a series of conversations with some of America’s most innovative chefs. I wanted to talk to them about their training, their ideas, their relationship to creativity and to change, and their hopes (and fears) for the future. I spoke to chefs about every aspect of their business. What is a restaurant? How can a chef ensure that a visit to their restaurant is something special? What is their philosophy of food? How do they make that philosophy work? What have they learned over the years? What have they unlearned? Where do new ideas come from? How do old ideas change? I wanted to speak to them, interview them, take their ideas and pick their brains before I took photos and picked their plates clean. When you get chefs talking about food in the right way, amazing things start happening. And they start wanting to talk about more than food, too. They wanted to design futuristic kitchen appliances and give me their B-side dishes. They wanted to cross over into their other enthusiasms: some of them have a deep well of information about music, some about movies, some about books, some about fashion, some about architecture, some about technology. I wanted to talk to them about whatever they wanted to talk about. I wanted to be in their conversation if they wanted to be in mine.

One question that came up over and over again was diversity. It came up as a question because there were no satisfying answers. The sad fact is that there’s not much diversity in the world of fine dining, or in what we know to be fine dining. I noticed it first as a diner. Sometimes I would visit restaurants and see pretty quickly that I was the only black person in the room. Those moments made it clear that I had been invited because of my celebrity, or because I could foot the bill. It wasn’t that I would have been disqualified because of my color, at least not in any overt way. But it was clear from almost any restaurant that diversity wasn’t a priority. Here, I’m talking not only about the people in dining rooms, but the people in kitchens. There aren’t large numbers of black or Hispanic chefs in charge of the country’s best restaurants. The same low-representation problem affects female chefs as well. The further I got into this book, the more I wanted to make sure that I handled the issue. But I wanted to handle it in a specific way. I knew from fairly early on that I didn’t want to artificially inflate the numbers of minority and female chefs I was talking to. That would have been a kind of tokenism, a gesture that would have sidestepped the problem. Instead, I wanted to talk to chefs and ask them, whenever possible, why they thought that the food world was so white and male dominated. Their answers were interesting, opinions coming from different parts of the country. Donald Link, in New Orleans, pointed to the fact that few young black men (or women) seem to work in restaurant jobs, wondering if the reason was related to the historical stigma associated with kitchen work in the African-American community. Daniel Patterson, in San Francisco, saw minority representation in the fine-dining kitchen—along with related problems regarding the eating habits of inner-city Americans— as a stubborn problem, but one that couldn’t be solved in food conferences or on Op-Ed pages. It was one of the driving forces behind his decision to create Loco’l, an affordable, real-food fast-food chain that would open its franchises in poor American neighborhoods. After I spoke to Donald, Daniel, and the rest, I started to read around on the topic. One of the best pieces I found was “Coding and Decoding Dinner,” an essay in the Oxford American by the Washington, D.C.–based food writer Todd Kliman. Kliman’s piece, which ran in May 2015, is about how restaurants are often careful not to become “black” establishments—and, specifically, how they are reluctant to cross the “60-40 line,” where more than 40 percent of diners are black. Many of the people Kliman interviewed wouldn’t go on the record. I didn’t have that problem. No one that I talked to shied away from the question. Most discussed it forthrightly, with a mix of frustration, optimism, clarity, and confusion. And yet, I still feel a little tug of responsibility that I wasn’t able to present a more diverse food world. The facts just don’t bear it out at the moment.

What the facts do bear out is that all of the chefs in this book are artists facing forward. This book, hopefully, both looks at things from their point of view and faces them directly. This is not your typical food book. It’s more about the ideas behind the food. Think of it as a tour through different food studios. It’s getting inside the minds of the artists. It’s the creative process of these chefs illustrated through photography: both in still lifes and action shots taken by a photographer whose work I greatly admire, Kyoko Hamada, and through my own Instagram. I’m a documentarian of all things, and this is no exception. It’s food I’ve eaten, chefs I want to understand, it’s somethingtofoodabout.

Reproduced with permission from Something To Food About: Exploring Creativity with Innovative Chef by Questlove. Published Random House (US). RRP $65.00. Text copyright ©Questlove, New York City, 2016.