Category — Features

Stone Soup Volume 7

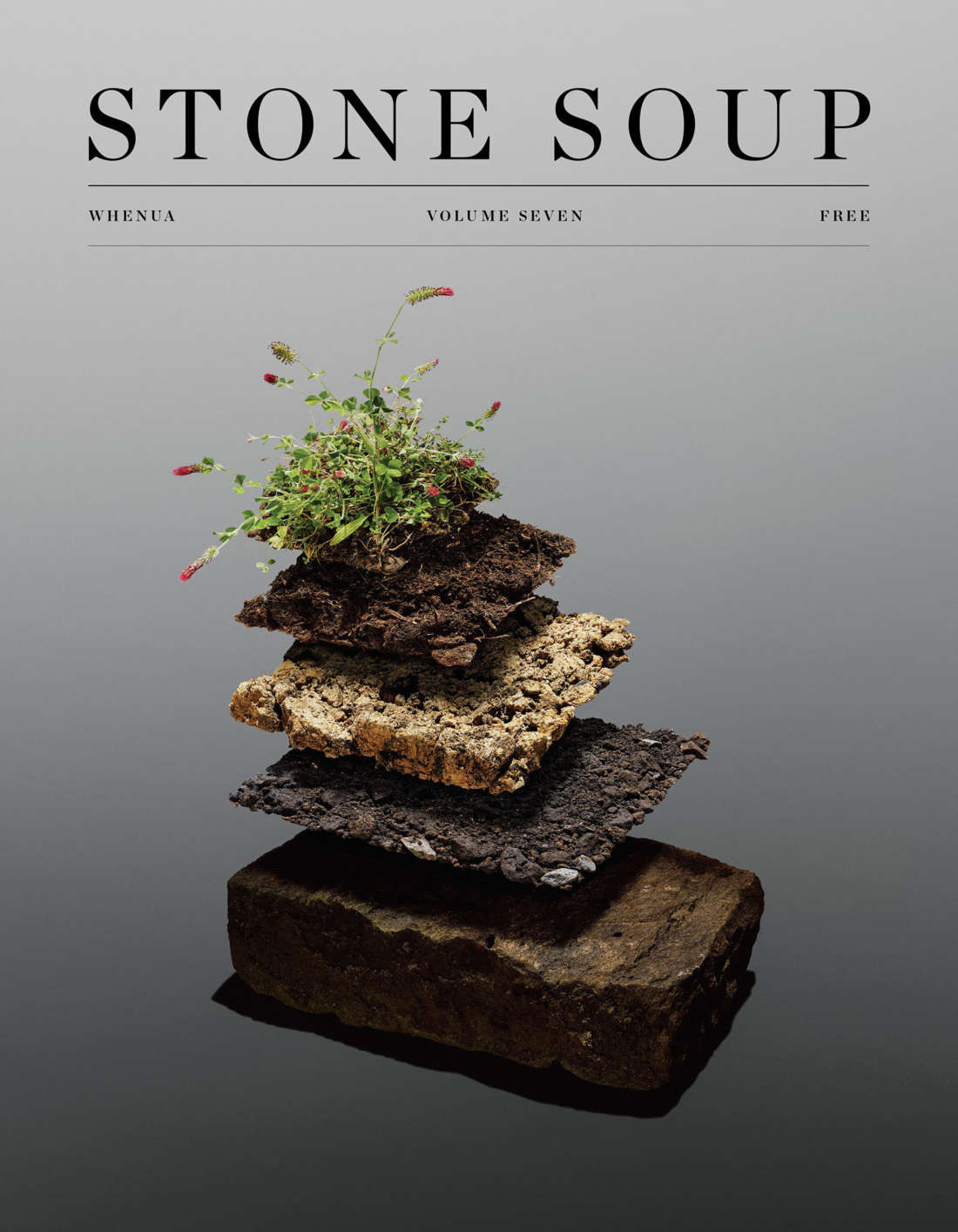

Ko au te whenua, ko te whenua ko au – I am the land, and the land is me.

On October 8th the International Panel on Climate Change reported that in order to avoid climate breakdown by limiting warming to 1.5°C, we would require a “rapid and far-reaching” reordering of society within the next twelve years, which Jim Skea, Co-Chair of IPCC Working Group III said is possible “within the laws of chemistry and physics but doing so would require unprecedented changes.”

Science tells us that global industrial civilisation is in conflict with physics and the natural world which sustains us. We urgently need to update to our 400-year-old operating system in order to avoid a very unpleasant adaptation to a heating world, as California has recently illustrated. And twelve years is not many ticks at the ballot box.

This information mostly instills despair and a death of hope in people, which risks rendering us collectively inactive – ‘caught in the headlights’. Gustavo Esteva proclaims however that “recovering hope as a social force is the fundamental key to the survival of the human race, planet earth, and popular movements. Hope is not a conviction that something will happen in a certain way. We have to nurture it and protect it, but it is not about sitting and waiting for something to happen – it is about a hope that converts to action.”

What does this have to do with a food magazine? Stone Soup has a mission to shun despair and shine a light on those people and actions which nurture hope. American farmer, poet and essayist Wendell Berry says “eating is an agricultural act”, and that “to be interested in food but not in food production is clearly absurd”, so this volume is a love letter to our land and a window to the magnitude of change which is not only possible but already in action, and in contrast to our agricultural history.

In Berry’s essay The Unsettling of America he poses a question we would benefit from asking ourselves in New Zealand – “how deeply rooted in our past is the mentality of exploitation?” Our nation was born at almost exactly the same moment and partly as a consequence of industrial agriculture. The founding economic principle of the pākehā state was to exploit, extract and export; and many who subsequently emigrated here had been unsettled by the fences which enclosed common land in the British Isles.

Raj Patel – interviewed in the following pages – suggests in his recent book A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things that we can find the roots of this mentality in the invention of ‘Nature’ in Western thought, and thus our separation from the living planet – neatly encapsulated in René Descartes “I think, therefore I am.” The individual human in Cartesian rationalism had risen above the earth, and men were proclaimed “the masters and possessors of nature”. Wendell Berry and the IPCC report suggest this is “a mentality whose triumph is its catastrophe.”

We don’t have a European peasant history which precedes this separation on this land, but we do have indigenous foundations we’ve neglected to hear. And so it is fitting that we start this volume with stories about Māori foodways, within which Hua Parakore (Māori organics) practitioner Dr. Jessica Hutchings offers an alternative to this Cartesian vision by proclaiming “I am nature, I feel myself as nature.”

Biodynamic winemaker James Milton shares this connection and suggests “we are not standing on dirt, but the rooftop of another kingdom” imploring us to “tread carefully”. Sadly half of the topsoil on the planet has been lost in the last 150 years, mostly through our agricultural practices. But we now know that photosynthesis can transfer energy into ecosystems by drawing carbon from the atmosphere and storing it in living soil – carbon sequestration through soil building is an existing (underutilized) climate mitigation technology. A UC Santa Barbara report states that “for every kilogram of vegetables you grow yourself, you’re reducing greenhouse gas emissions by two kilograms, compared to buying from the store.” Your backyard and the farms you buy your food from can be carbon sponges – if you so choose.

This volume tells a variety of intersecting stories which attempt to answer the question of what a careful contemporary regenerative ‘agri-culture’ could look like: small, diversified, biological, hands-on, hyper-local, urban, suburban, rural, abundant, generous. One which practices ‘artisanal small-batch soil-making’, has no concept of waste, consumes fewer and better cared for animals, embraces digital connectivity, acknowledges indigenous values and wisdom and the work of women in our landscape, cultivates community and seeks sovereignty in our relationship with food.

Berry concludes his essay by suggesting that “the care of the earth is our most ancient and most worthy and, after all, our most pleasing responsibility. To cherish what remains of it, and to foster its renewal, is our only legitimate hope.” Our food system, currently the biggest villain in many of the troubles we face, viewed through a different lens and with our active participation, could be our biggest and most delicious solution.

‘I eat, therefore I farm.’

By Aaron McLean.