Category — Features

Return to Parihaka.

Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua: I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past.

I’d never been to this part of the world before, I’d never sat under the gaze of the omnipresent Mt Taranaki. He is truly magnificent, in the most breathtaking way. It’s hard to understand how he could have lost a love battle against Tongariro for the beautiful Pihanga. He has my heart immediately. I couldn’t stop staring at him as we travelled down Surf Highway 45 towards Parihaka.

Enveloped in green paddocks, the road winds its way through some of the strangest-shaped landscape. The large mounds and hillocks were made when the mountain, in a sort of wicked cherry-spitting competition, spat house-sized boulders around him during the eruption. Some were clumped together, others, closest to the coast, were obviously the prize-winners.

And now they’re covered in pasture as Papatūānuku slowly reclaims them, perhaps to regurgitate again one day.

The green grass and cows seem endless here, as if it was just easier to choose the large brush than a finer tip of diversity to go around all the lumps and bumps.

The singularity of the landscape sits with me as we head down a dirt road right to the coast.

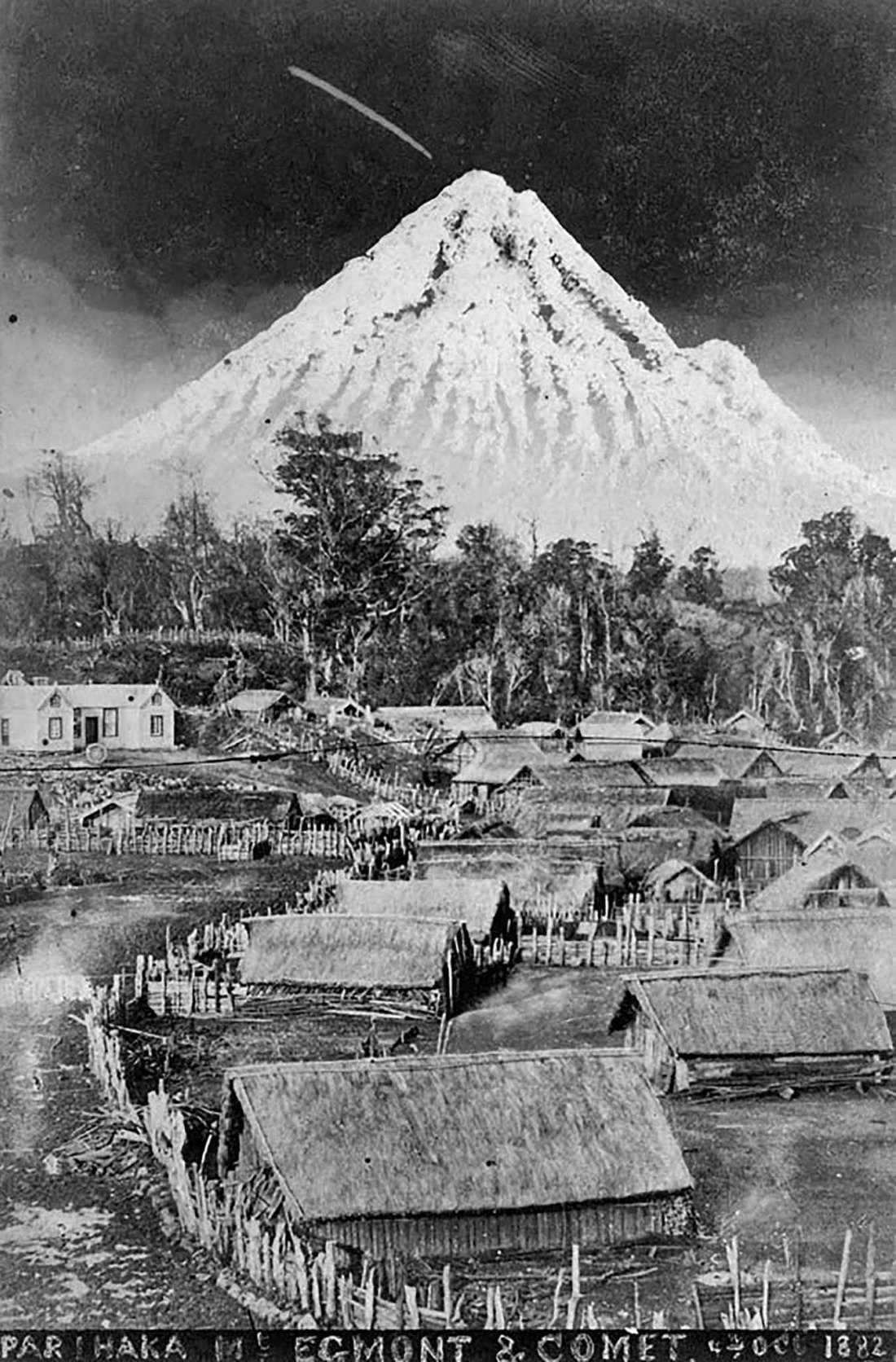

The story of the Māori settlement of Parihaka exists somewhere in the consciousness and conscience of most of us, or at least it should. On November 5th 1881 government troops invaded this place that had come to represent peaceful resistance. The sense of self-governance was surely the threat and much of this must have been because of their ability to be self-sufficient. In many ways it is one of our most important examples of food sovereignty.

1.5 million acres of Taranaki land was confiscated in a war started by the government on March 17 1860 in Waitara. These wars soon spread to Waikato, Bay of Plenty and the East Coast. Much of the North Island was impacted by the social ills of land loss and poverty by both the war and then the Native Land Court. Parihaka provided refuge and sustenance of wairua and tinana. It’s hard to imagine the frame of mind of the people as they were forced from their land. Te Whiti was a leader and prophet. The resistance movement based at Parihaka was led by him and Tohu Kākahi. I’ve often wondered how these men convinced retreating warriors to give up their weapons and pick up a plough.

He kai kei aku ringa

There is food at the end of my hands

We almost go past the driveway, and reverse quickly enough to see a man planting a seedling in his garden. Tihikura Hohaia welcomes us in a way that is truly who we are; part challenge, part warmth, all welcome. I love this about my country. I see it replayed over and over again, no matter what our ancestry. Forceful thrust of the handshake, eye contact, measuring of the visitor, and then acceptance and openness. Tihikura gives us his mihi and we’re left without doubt that Parihaka is his place to stand, his turangawaewae. Aroha, his partner, steps forward and we’re totally captured. Somehow she seems to slow the world beyond this place and we’re bought completely into the moment.

I’m here with Nadine who’s helping me understand the food story of Taranaki. We’re here to listen to some pūrākau; story-telling about Parihaka, to understand its narrative and why we’ve all found ourselves here together.

The confiscated land around Parihaka was essentially abandoned as the troops moved on, so the people of Parihaka replanted them with kumara, large scale gardens and sustainable farming while waiting for the promised government reserves. Then in 1878 with no sign of reserves being allocated the government sent the Armed Constabulary disguised as road builders and surveyors across the Waingongoro river and the southern boundary of Parihaka to begin establishing European farms. This was when Te Whiti and Tohu responded with the fencing and ploughing campaigns leading to the large scale arrests and imprisonments of Parihaka men.

This must be the ultimate act of defiance, because what is the value of land if it’s not to sustain you and your community. Who truly owns a piece of land if they don’t farm or gather from it?

Ehara taku toa i te toa takitahi engari he toa takitini.

I come not with my own strengths but bring with me the gifts, talents and strengths of my family, tribe and ancestors.

Tihikura & Aroha’s whānau papakāinga sits precariously on the western coastline. They’ve noticed changes lately as the salt-laden winds and the rising sea levels have encroached further inland stealing the life from their frontline shelter and affecting the story beneath it. Despite these obvious challenges, they’ve created a wonderfully abundant garden, filled with inherited knowledge including seaweed-laden taewa rows and harakeke strung together as mulch mats. Tihikura uses Maramataka (the Māori lunar calendar) and explains how the moving seasons played a huge part in the cycle of the Parihaka community. I’m reminded of the prevalence of European biodynamics in our pākehā growing and wonder how we missed this much stronger connection to our land.

But even as we marvel at the resilience of this food garden Tihikura helps us understand that this cultivated space is just a fraction of his environment. The real garden includes much more of the landscape. He talks about the traps designed in the surf to catch kahawai and the river’s abundance including īnanga and the highly revered piharau.

We move back to the verandah for kawakawa tea with honey from their hives and Aroha tells us about the Kai Oranga programme she is studying which seeks to re-find knowledge about sustainable food production and understand the connection between this and people’s wellbeing (rongoa). I have a moment of realisation about how much permaculture (something I’ve practiced for the longest time) originally drew from this indigenous knowledge. Again, this feels like we’ve missed something in Aotearoa permaculture conversations.

And as Tihikura continues to korero it’s not hard to imagine forest covering the grassy knolls beyond his boundary and the huge amounts of bird and plant life that must have delivered. We’re transported to another place, to a time of abundance, and self-sufficiency. The land here, with its volcanic soils is so fertile it feels like it could feed everyone forever.

Taranaki is second in New Zealand GDP per capita in food production by region. Over 50% of Taranaki’s manufacturing base is dedicated to food processing. Taranaki’s top three food production sectors are cheese & dairy production, meat processing and poultry. Buy a burger and it’s likely you’ll be eating cheese made in Taranaki. The region is cheese HQ for the quick service industry. Taranaki does not have a single small cheese producer.

Tihikura is doggedly and determinedly sitting on the literal and metaphorical edge of the industrial agriculture that surrounds him and he has noticed the changes in his awa (river). So much so, he’s started to document them on video. The algal blooms that sometimes sit just off the coastline reduce visibility and his ability to catch or find food.

And yet today lunch is completely satiating. Fresh salad and wild greens including kokihi. There’s creamed paua, a huge whitebait fritter, taewa and parāoa . It’s as if all the story-telling has manifested on the plate, and we sit down to enjoy it as Tihikura picks up the guitar.

So despite all these challenges; the climate disrupted winds, the small amount of fertile land left with his family, the huge environmental impact of industrial agriculture, Tihikura had a moment of recognition that day of exactly what we all see in him. A story-teller, a holder of an epic amount of knowledge and understanding of this place, a guardian, a kaitiaki, a truth-bearer, a watchman, a sentinel as much as the lighthouse to his south.

He’s an environmental warrior whose weapon is his plough.

Time passes in a heartbeat and I come away with an overwhelming sense that there are powerful values or kaupapa that are trying to make themselves known from this place.

Perhaps it’s time we all returned to Parihaka.

Puritia ngā taonga a ngā tūpuna mō ngā puāwai o te ora, ā mātou tamariki

Hold fast to the cultural treasures of our ancestors for the future benefit of our children.

For further reading Tihikura & Aroha recommend;

The Parihaka Album & Ko Taranaki Te Maunga – Rachel Buchanan

Ask that Mountain – Dick Scott

Days of Darkness – Hazel Riseborough