Category — Features

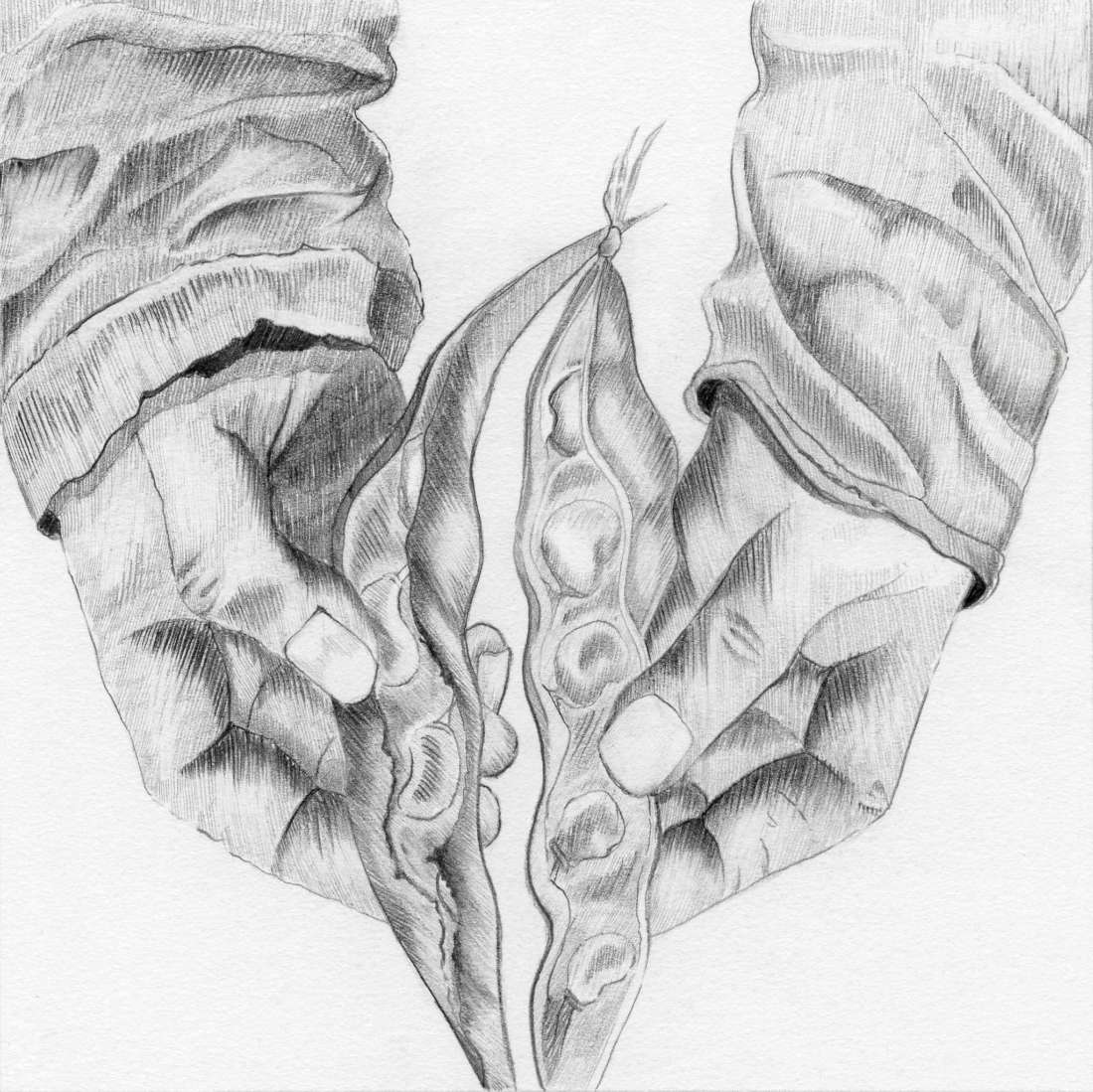

Saving Seed

“They tried to bury us. They didn’t know we were seeds.”

— Mexican Proverb

To love to eat but not cherish the seed is a tragic unintentional forgetting. A seed is a giver of endless bounty, a tiny perfect boundless package, a time capsule, a blueprint of life. Perhaps nature’s greatest technology. Without seeds we have no food and without food we have no life.

Seeds are abundant, or at least they should be. Each plant will produce a generous bounty with which to reproduce, each seed a repository of energy and information — the legacy of billions of years of evolution, and more than 10,000 years of human selection for agriculture — with which to grow the energy and nutrients that nourish our growth and enable us to thrive. Nature needs little intervention in order to be generous. If I let one lettuce go to seed, not only do the bees in my neighbourhood get nectar from the flowers, everybody I know can eat lettuce for free – forever.

Yet rather than holding the seed in reverence, cherishing it as a sacred gift, we take it for granted. And this neglect has put our seed, and therefore our future ability to feed and nourish ourselves, at risk.

Since humans have been agricultural beings we have saved seed, but in only the last 60 or so years — as we moved off the land and into cities, outsourcing our sustenance to the market, perceiving ourselves to have progressed by reducing the percentage of farmers in the population from a historic norm of 60 to 75% to less than 5% — we have been taking our seed for granted. The ‘developed world’ has lost 94% of the genetic diversity in our vegetable seed in the 20th century (75% lost worldwide) as fewer and fewer farmers have abandoned multiple local varieties for commercial, genetically uniform, high-yielding seed.

Diversity is not only resilient and nutritious, it’s delicious and interesting as well. Variety is the spice of life they say, but most of humanity now subsists on a diminishing array of foods; beans, corn, rice, barley; with a smattering of vegetables; potato, carrot, onion, garlic, celery; uniform and polished, available all year and shipped around the globe. The medley on our plate severely diminished and the resilience of our food system — especially confronted with the spectre of storms and drought in our changing climate — at serious risk.

Is the loss of sovereignty and security progress? The loss of flavour, nutrients and genetic information accumulated over millennia? Once they’re gone, they’re gone. We can’t regenerate this genetic information. In a recent PBS documentary, SEED: The Untold Story, seed saver Will Bonsall proclaims that, “Genetic diversity is the hedge between us and global famine”.

Kay Baxter is a hero of diversity preservation in New Zealand, having dedicated her life, through the Koanga Institute, to preserving and making available quality organic heirloom seeds, a gift of immeasurable value. But I heard Kay warn us last year at the ConversatioNZ symposium that she and her partner Bob Corker could no longer be the sole security against the loss of diversity of New Zealand’s seed legacy. The plethora of seeds they maintain, bred here, by our ancestors, to be resilient and abundant in our landscape and climates are at risk. Diversity is resilient, but the problem, as Gabriel Howearth is quoted explaining in Kay’s booklet, Save Your Own Seeds, “is that the diversity is disappearing, and we can’t wait for the experts to take responsibility…all of us have to take responsibility for preserving what diversity we can.”

Seed diversity has suffered from market failure. Agricultural corporations whose sole remit is the highest yield – in the monocultural field as well as the balance sheet – have diminished our natural capital, nurtured over thousands of years by thousands of people. But we all, in our absence of awareness, have allowed this model to land us here. Caught in our mythology of progress, food production beneath our loftier pursuits, we have entrusted this once vast store of information to a powerful few.

If we want a resilient, diverse nourishing food basket, we need to participate and be active in its preservation. We — you and I — need to be a distributed network of seed savers. Only then, when seed lives as food in all of our gardens, are we immune from the generous few who have already gifted us more than 30 years of service losing the energy and resources to act on our behalf, or from the quarterly balance sheet deeming diversity inefficient. And we can’t rely on institutions maintaining seed banks in arctic vaults, where diversity is preserved, but static, not alive in the field continuing to evolve. As Will Bonsall says, “Life does not go on in an ark.”

So this is a call to arms, or garden forks. Plan to get your hands in the dirt this spring, buy organic heirloom seed from Koanga, or organic seed from a supplier or friend you trust. Grow robust organic vegetables, let the best of them flower and feed the bees and butterflies, and then learn to save your seed. Or let nature take its course and allow your garden to sow itself. And next year, with more seed than you’ll ever be able to plant, gift some to your friends and encourage them to do the same. Through a little effort, not only can we better nourish ourselves and our immediate ecology, we can turn around the aberration of the last 60 years, and progress to a place that honours the legacy of all those before us who understood the importance of cherishing biological diversity and the living treasure of seeds.