Category — Features

Home, land and sea

I recently interviewed an inspiring group of food thinkers – chefs, critics, farmers and eaters* – and asked them whether we could define New Zealand’s food culture, whether we had a distinct cuisine and whether it mattered.

Individually they sung in harmony, including those visiting from abroad: it didn’t matter, it’s an evolution, we’re multi-ethnic, young, full of opportunity. But they also all agreed that what will ultimately define a distinct New Zealand cuisine and help bring it to fruition is us learning to become fluent in this place. To draw inspiration from our environment, our endemic species and most importantly, our indigenous culture and its knowledge of the ingredients and techniques that are unique to this land. Looking less to mimic Tuscany or Copenhagen or Los Angeles and falling in love with where we are, Aotearoa.

This quest is quickly becoming much more evident in more of our restaurants and even in some of our home kitchens, and paradoxically has been led mainly by recent immigrants. But from where I’m standing, one of the people digging the deepest, decolonising her psyche as well as her kitchen, is Monique Fiso. Of Māori and Samoan descent, trained in fine restaurants in Wellington and New York, Monique has returned home with a renewed fervour (inspired by others’ interest in a culture she had been detached from), on a hunt for a foundation from which to speak our culinary language. She is delving into Aotearoa’s history in pursuit of a relearning of pre-colonial Māori knowledge, currently expressed through her Hiakai pop-up, but reverberating well beyond.

I asked Monique for her thoughts on why we should be excited by our indigenous ingredients, where the knowledge went, and whether she could share with us some of what she’s learned.

Why do you believe we should be using indigenous ingredients in our everyday cooking?

Well, why not? It’s a great way to experience our culture in your own home. Also, using something that grows locally is surely better than using something that has to be sent from the other side of the world. With climate change hot on our heels, it makes sense to try to reduce our food miles to give the planet a break.

Why is it so uncommon to use foods indigenous to Aotearoa when we cook?

Lack of knowledge and accessibility. Most people don’t know what our indigenous herbs look like, let alone how to use them in cooking.

Kawakawa leaves and berries – Piper excelsum or kawakawa is one of the more commonly used endemic species. The leaves can be infused for teas or marinades and the berries used for their peppery flavour. Kawakawa is a traditional medicinal plant for Māori and is also commonly used to welcome people onto the marae, and at tangi wreaths of kawakawa are worn as a sign of mourning. The leaves can even be burned as an insect repellent.

How was this knowledge lost?

Māori history and knowledge was almost always passed down orally, so not having written texts to refer back to makes it difficult. I would say the Tohunga Suppression Act of 1907 played a big role in losing our knowledge, but I think urban drift was the main contributor to the disconnect. Before World War II, most Māori lived in rural communities and had close relationships with kaumātua and their respective maraes. During WWII, many Māori moved into cities for job opportunities in industries that were assisting the war effort. This saw 26 per cent of Māori move out of their historic communities, and by 1986 this number had increased to 80 per cent. You’ve got to remember that the options for communication were very limited compared to today – it’s not like they could’ve kept in touch with everyone back home via Facebook.

How have you attempted to rebuild this knowledge?

I’ve attempted to rebuild it by putting together pieces from what has been recorded by early European settlers and the knowledge that has survived in Māoridom. Elsdon Best documented life among Tūhoe extensively in the late 1800s to early 1900s and his books have a wealth of knowledge regarding day-to-day Māori life during this time. William B. Otorohanga published a book in 1904 called Where the White Man Treads, which I frequently reference for information. There is a fantastic chapter in there that goes into great detail about hāngī and recounts watching a Māori woman (yes, a woman!) put one down for everyone to eat in the evening.

Horopito – Pseudowintera or horopito is often referred to as pepperwood as its leaves have a hot, peppery flavour. Horopito leaves are usually dried and ground to a powder to use in marinades or sauces. It also has a number of traditional medicinal uses and contains a substance called sesquiterpene dialdehyde polygodiali, which is antifungal, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and antiallergic.

Tī kōuka shoots – Cordyline australis or tī kōuka, also known as cabbage tree, gets its English name for a reason. When you harvest the new shoots growing at the top of the tree and peel away the tough outer leaves, you reveal a tender white heart, both bitter and sweet, which looks like leek. It can be sliced and eaten raw or cooked.

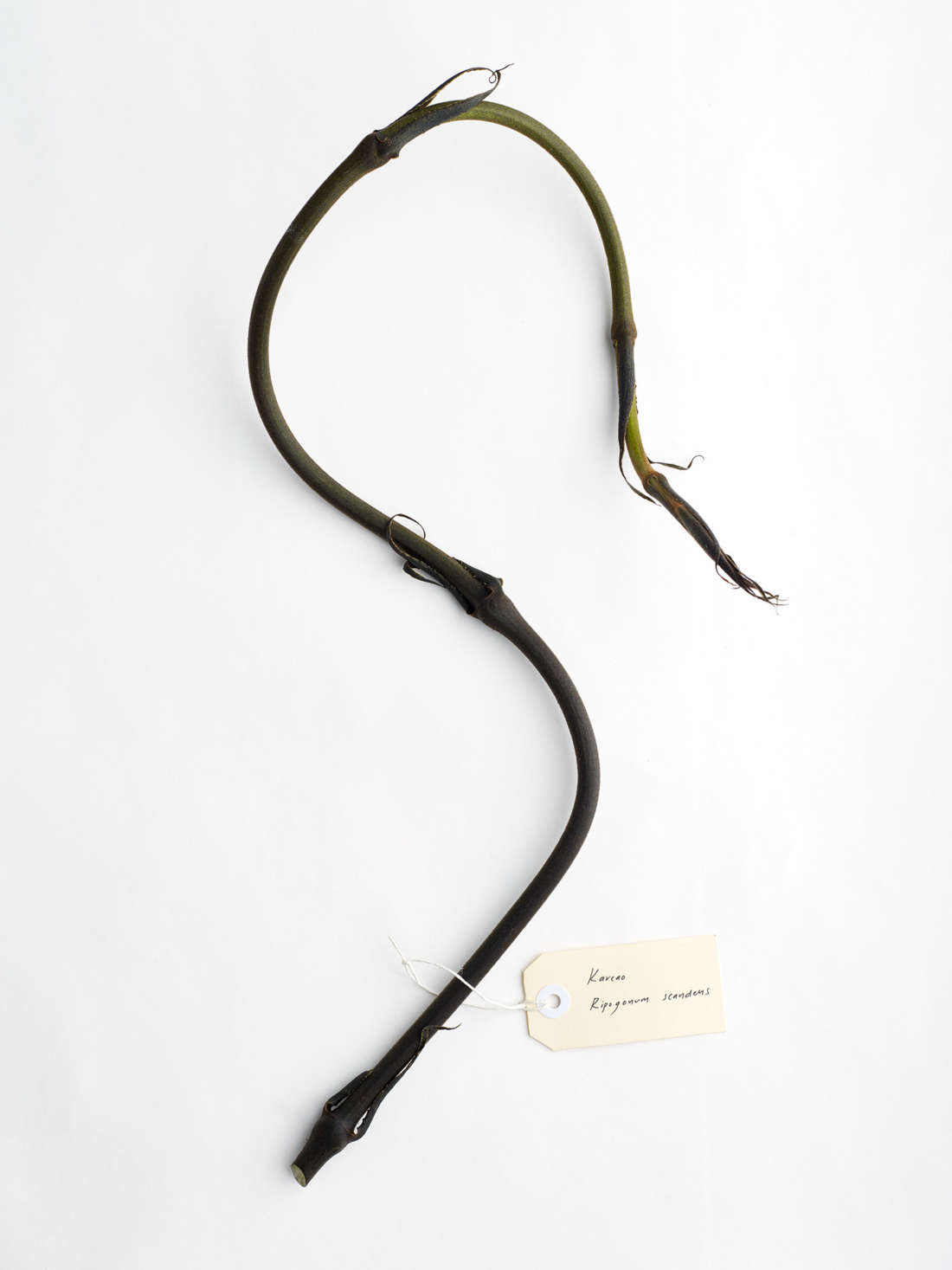

Kareao – Ripogonum scandens, commonly known as kareao or supplejack, is a common rainforest vine native to New Zealand. Often referred to as bush asparagus, the new growth at the tip of the vine can be eaten raw or cooked. Kareao was also used medicinally for a variety of conditions.

What inspired you to try?

I’ve always had three passions in my life – cooking, history and art. If I wasn’t a chef, I would have probably become a historian. Combining two passions (cooking and history) to create the third (art), feels like a natural path for me to take. I also wanted to challenge the public perception of Māori cuisine, and prove that it could be just as sophisticated as other cuisines that are more revered.

Would you like to see some of these ingredients on our supermarket shelves? If so, could they be foraged or is it an opportunity for some rewilding of our land?

I would like to see horopito, kawakawa, urenika, kamokamo and more shellfish available in our restaurants and supermarkets, but before that can happen there needs to be a much more streamlined supply line. I find it rather depressing that nine times out of 10 you can’t even buy pipis at the supermarkets, and more often than not there are only two varieties of New Zealand fish. There is an opportunity for some rewilding of our indigenous produce and there are companies in NZ who are working on this right now, which is really exciting, but there’s also nothing to stop us from planting these ingredients in our own gardens. Good for food, medicine and our ecology.

Is it cool for people to head into the bush and forage for this stuff? Is there etiquette we should understand before we do?

It is cool, BUT there is some etiquette that should be observed before taking from the bush. The first would be to check what the Māori lunar calender says about harvesting on the day that you are planning to go out. For example, if it’s a rest day according to the calendar, don’t go out, and if it’s raining, don’t forage. Breaking these is considered incredibly disrespectful.

If you’re in the clear, then say a small karakia before taking anything from the bush or sea. It doesn’t have to be complex or in Māori, just give thanks to Tangaroa and/or Papatūānuku for what you’re about to take. Lastly, and I think this one should be obvious, don’t be greedy! Take only what you need and do it in a way that doesn’t damage the environment.

What are your favourite discoveries and can you share some tips on how to use them in our everyday cookery? We all know we can make kawakawa tea, but how can we use it this summer at a barbecue?

Favourite discoveries have been our native berries. For example, karamu berries grow all over the country – they have a bittersweet flavour. They can be used in desserts or as the base of vinaigrettes. Kawakawa and horopito are great bases for spice rubs that you can use to marinate meat in for barbecues over the summer.

Mamaku – Cyathea medullaris, or mamaku, is often called the black tree fern and the young unfurling fronds/koru can be eaten. It has been likened to sago due to its slimy texture, and once you peel its outer skin it can be eaten raw, cooked in the hāngī, boiled, pickled or used as an ingredient in soups. The gum can be used to treat cuts or burns and you can steam and mash the pith to use as a poultice.

KAWAKAWA PORK SHOULDER

For the brine

5kg pork shoulder, bone in and skin on

2 litres water

25g iodised salt

10g sugar

1 white onion, sliced

3 garlic cloves, smashed with the back of a knife

5g black peppercorns

10 kawakawa leaves

Cross hatch the skin of the pork shoulder. Bring 1/4 of the water (500ml) to the boil with the salt, sugar, vegetables, peppercorns and kawakawa. When the mixture has come to a boil and the salt and sugar have dissolved, remove the pot from the heat and add the remaining water. Leave to cool completely then add the pork shoulder and allow to brine for a 12-24 hours in the fridge.

For the rub

200g soft brown sugar

30g iodised salt

40g dry mustard powder

20g onion powder

30g dried kawakawa**

5g ground black pepper

Combine all the ingredients in a bowl. Remove the pork shoulder from the brine and leave to sit at room temperature for at least 30 minutes before rubbing with the mixture and roasting in an oven preheated to 165°C for 2-3 hours or until the internal temperature reaches 85°C. Remove from the oven and leave to rest for at least 30 minutes before slicing.

Serve with fresh greens and a potato salad.

* I interviewed these people at this year’s Eat New Zealand symposium in Wellington. To see the video head to our website: Eat New Zealand, Now we're talking.

** To dry kawakawa leaves, remove the stem, lie flat across trays in a dehydrator and leave at 70°C overnight. Alternatively, leave overnight in a really low oven (50°C-70°C).

Photos: Aaron McLean.