Category — Travel

Ghost Soup

A tale of fermented fish brine.

A hot day, a deserted ferry terminal. Beneath the beating sun on the concrete dock, a man swings a pickup truck around to the front of the waiting area, gestures at us to hop in the back.

The man is Eisaku Fujii, the president of the Niijima Fisheries Processing Industry Cooperative, and he’s here to take us to the kusaya processing plant. We met Fujii-san earlier in the afternoon, at the ferry terminal gift shop where he talked us through a freezer full of butterflied, semi-dried fish ready for visitors to carry back to the mainland. Aomuro, tobiuo, muroaji: not the usual species of himono we’ve grown to love in Japan, but unfamiliar names, small shiny silver fish. Island fish.

They looked harmless enough, but then Fujii-san walked us to a refrigerator and unscrewed a small jar full of bite-size fish pieces to sample. Even from a few feet away the odour was overwhelming: somewhere between smelly feet and a pile of dirty nappies left festering for a few hours on a warm day.

Taking a bite only intensified the stench. It wafted up past our taste buds into our nasal cavities, up the back way. My throat threatened to close up. I tried to get it over with but it was stubbornly chewy, and the more you chewed the more odour it released, until the assault was overwhelming. Imagine gnawing on beef jerky cured in horse manure and you might get the idea. This was no ordinary fish.

–

The truck bounces inland, through a nondescript cluster of fading concrete buildings. Past roads leading to dead ends and overgrowth, deserted parks and beaches empty now that last century’s surfing boom has all but dried up.

If you were to describe it as an island paradise, well, you’d be stretching it. But we’re bathed in the light you only really get on islands, sunlight reflected and magnified millions of times off each wave, each ripple of the miles of sea all around. Tufts of low, incandescent cloud cling to steep, bush-clad hilltops looming above us a deep green. And we see the water: calm, blue, clear; the sand a dusty white. If you squint, you can almost see how it sometimes gets compared to Hawaii. There’s something raw, alive about this place.

–

Ask anyone to name the world’s smelliest foods and they might say durian, the rugby-ball sized, custard-like fruit, whose odour is so powerful it’s famously banned from public transport in Southeast Asia. Or natto, the slimy, fermented soybeans from Japan, often likened to the stench of stinky feet. They might name any number of kinds of pickled or fermented fish found in Scandinavian countries.

But durian smells rich and sweet. Natto? Chuck some shoyu and mustard on it and eat it with rice– child’s play. You wouldn’t be wrong with the Nordic fish, though– studies of stinky foods from around the world have crowned surströmming, the fermented Baltic herring found in Sweden, with the title of world’s most pungent-smelling food. Next up is hongeo-hoe from Korea, made with raw skate traditionally left to ferment in compost or under straw (or, more likely these days, in a carefully temperature-controlled refrigerator). And then there’s kusaya, the dried fish preserved in a fermented brine, produced on the islands south of Tokyo.

Its hallmark odour comes from ammonia and sulfuric compounds and broken-down amino acids with names like putrescine and cadaverine, the very chemicals that form when dead bodies and animal carcasses are left to rot. Unsurprisingly, kusaya is a divisive food outside its islands of origin. Though it’s unarguably healthy — rich in B vitamins and calcium and niacin, high in probiotic benefits from the fermentation process, and lower in sodium and higher in protein than other types of dried fish, the smell is overpowering, especially when the fish is grilled. There’s a restaurant in Tokyo that will serve kusaya to you only if you reserve a private, smell-proofed room to cook it in.

Kusaya is produced throughout the Izu shotō, a dozen-odd rocky, volcanic islands extending several hundred kilometres south of Tokyo. And while these days you can even find it on the mainland– especially around the Izu Peninsula southwest of Tokyo– there’s said to be none more intense in aroma than the kusaya produced on Niijima, the birthplace of the stinky fish.

We pull up to a squat concrete building dappled with sunlight. Inside the processing plant, Fujii-san shows us where the kusaya is made. It’s a hot day, easily in the mid-thirties, and the stench is overbearing. We’re suffocating. But Fujii-san just laughs: it’s the middle of the summer holidays, and production has been on hold for a week. “On a scale of 1 to 10? No one is here– this is a two.”

He explains the process. Freshly caught fish is gutted and cleaned before being soaked in a fermented brine called kusaya eki, then washed again and left to cure in the sun until it’s more or less shelf-stable.

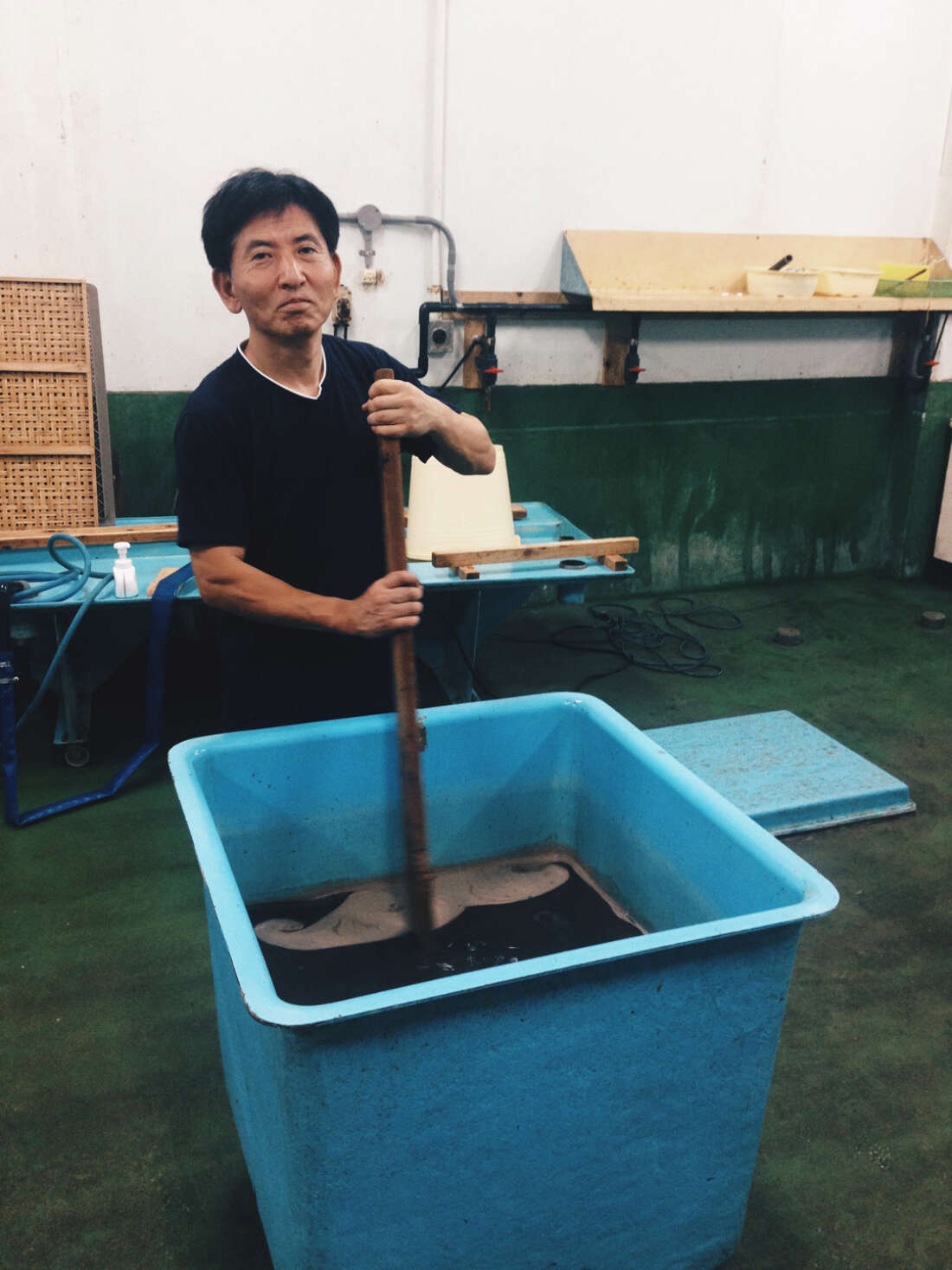

There’s a misconception that the powerful, rotten smell of kusaya comes from decomposing fish innards, that the fish is fermented without being gutted. But kusaya is actually very clean, Fujii-san says. The smell? That comes from the brine. He gestures to the row of industrial-size buckets in front of us. They’re filled with a deep brown, frothy liquid. Using a long wooden paddle, he stirs one of the vats; the liquid seems at once viscous but also watery, the aerated foam rising and dancing at the surface, almost irritated at being woken from some kind of murky slumber.

–

There’s evidence that people have lived on Niijima since the Jomon period, thousands of years ago. But aside from the odd bits and pieces of pottery we know little of what the islanders were doing here for all that time. I guess fishing and surviving.

By the Edo era the island was home to several fishing villages and a handful of exiles, mostly political prisoners from the mainland– monks and artists and poets who had been banished for some perceived slight against the ruling samurai classes– who were often welcomed by the villagers and were said to have made valuable contributions to the community.

And I suppose the community needed whatever extra help it could get, because this was a place with a unique tax problem. The ruling shogunate taxed most of Japan in rice, but Niijima, with its steep, plunging hillsides and rocky outcrops, had a severe lack of arable land for the creation and irrigation of rice paddies.

So the islanders paid their annual tax in the form of salt. You would think there’d be an abundance of salt to go around, Niijima being surrounded by the sea and all, but the demands from the shogunate were so high, the salt harvest so labour intensive, that gathering salt was an all-hands effort. Any salt left over was used sparingly. (To give you an idea of how serious the island took this endeavour, there’s anecdotal evidence that during the Edo period, anyone caught taking salt for unauthorized personal use would be cast off from the island along with their whole family.)

As a fishing community, of course, the islanders’ main source of protein came from the sea. But unlike the rest of Japan, where fish was traditionally preserved in salt before being dried, the Niijima islanders took an unconventional approach. In order to waste as little salt as possible, raw, cleaned fish were brined in a liquid originally made from seawater and then reused over and over again, until the liquid gradually grew richer and murkier and more pungent as it reached peak fermentation.

Kusaya brine was as essential to a Niijima household as the nuka (fermented rice bran) used to make pickles was for mainland Japanese families. It would be carefully maintained and passed on over the years, over decades and generations, until no one could even remember who made the original batch, or exactly how old it was. If someone moved to a neighbouring island, their grandmother or aunt might send them on their way with a carefully-packed portion of the family brine, to cultivate and keep alive for the next generation.

Over time, younger generations left the remote island shores for jobs in Tokyo and other cities on the mainland. Electricity and refrigeration reduced the need for traditional preservation methods. The number of kusaya producers on the island dwindled to a handful of families, most of whom relocated their operations to the plant we’re visiting today.

As Fujii-san stirs the brine, the smell in the room grows stronger. This substance is quite clearly alive. “This vat here?” he says. “It’s over three hundred years old. Want to taste it?”

I’ve forgotten that I was close to gagging only moments before. The urge to run out of the stifling funk and back into the hot ocean breeze has disappeared. Something in the room has shifted.

It occurs to me that this liquid I’m standing in front of is the last surviving remnant of a time no one alive today can remember. It’s seen hardship and famine, the lives and deaths of generations of islanders. Impoverished fishermen, samurai-era traders, political exiles, artists and poets, the arrival of electricity, war, even an improbable boom of tens of thousands of surfers who descended on the island during the late twentieth century. This broth has outlived all of them. It’s still fizzing away.

What was initially a clever workaround to ensure a steady supply of protein for the islanders while they toiled at collecting salt, on a remote mass of rhyolite somewhere in the Pacific, has produced this foul-smelling soup carrying the ghosts of all who came before us.

I hold out my hand. Fujii-san holds up the paddle. The rich, brown liquid runs down the side of the wood and drips onto my finger. I pause. I lick it.

Nothing miraculous happens. No samurai spirits whisk me away to some foregone era, nor does some fisherman’s grandmotherly ghost visit me with a kind smile. In fact, in that moment it hardly even smells.

–

This story was written in conjunction with Fun Radio From Japan, an independently produced documentary podcast exploring the lesser-known sights, smells, and sounds of Japan. Episodes 1 and 2 take a deep and irreverent dive into the history and culture of the island of Niijima and its stinky fish. To hear the rest of our conversion into kusaya connoisseurs, tune into funradiopodcast.com

Illustration by Tom Ryan