Category — Features

Turning Gold to Lead

“All we want is our fucking fish back.”

Nate Smith, of Gravity Fishing, a third-generation fisherman from Bluff, tells it like it is.

In the wake of a global crisis, he’s emphasising how things that were typical before, look absurd now. He’s real, raw, and it’s getting him indoors. People are listening.

“The current fishing model is outdated. It doesn’t work and doesn’t give back – it’s extraction, we’re depleting fish stocks.” Nate blames the disconnect and disillusionment of the fishing industry on its current giants.

“Every day they operate, they make it less sustainable. When small-scale fishing operations are more endangered than the Māui dolphin, and the only option is to funnel into mass production, there’s clearly a disconnect between hook and plate. That’s why it’s so hard to get fish in NZ. My goal is to secure Kiwis the right to the seafood around them. Nobody should have the right to own a wild seafood resource. Quota management is complicated and hard to comprehend, but in simple language, it allows a company the right to own a wild food resource. Doesn’t that sound funny to you? What gives you the right to own blue cod? New Zealand fisheries have been given an epic resource and they’re turning it into a second-grade product. You just accept it. But that’s not good enough. It seems criminal when I recite it.”

Gravity Fishing was having a moment right before COVID-19. Nate says the whole hospitality industry was. He has the records to back it up. Over 25 species of whole fish were being delivered to creative chefs across the country – chefs who treat the whole fish like it’s just another protein, cook every part of it, and understand the importance of taking pressure off the fish stocks.

“People like Lucas Parkinson, of Ode, Sam Gasson at Moiety, and Giulio Sturla ex. Roots. They’re blitzing and dehydrating the fish for texture and flavour. Offal is used in sauces, fish heads in broth. Crispy eyes are made into crackers. They’ll serve you an 80ml cup of deliciousness made from our product. People look up to these chefs. They have the platforms to amplify the story and educate people how to use the whole fish: nose to fin. Most people have little understanding of the anatomy. It weighs me down. I see all these people, many with rural backgrounds who have no idea about breaking down a fish. It comes down to the convenience of throwing a fillet in a frying pan. Convenience is crushing education.

For every thousand kilograms you’re catching for fillets – you’re throwing 1600kg of fish over the side. And that, for me, is a big thing that needs to change pretty much overnight. You’re paying for the whole fish anyway; you should use the whole product. A whole fish comes with its own quality assurance, too. It’s easy to mask the smell of old fish in a frozen fillet. You can’t do that with a full fish.

When restaurants closed across the country in March, I lost my customer base, but the demand for nutrient-rich protein was still there. In the first 72 hours, 350kg fish was ordered by locals. These new customers had a different kind of connection with Gravity than the chefs. They knew me and what I stood for, but I didn’t yet know who they were. They were full of empathy and looked to me – the fisher – for help. They had so much trust. We were feeding their families, and providing consistency, and quality.”

Networking between small food producers happened almost overnight. We swapped fish for lamb and mushrooms and wine to feed our communities.

I didn’t understand the importance of small scale until those first few days in lockdown. I felt a sudden heaviness from others, having lost everything – their livelihoods, their dreams – and they’re coming to me. I’m just the dude that catches fish at the bottom of the South Island. That was the moment I knew that the future was small.

Innovation needs to happen. And help needs to happen. But that means fucking with the big guys.” Nate’s future of the fishing industry looks like many small independent fleets, of local fishers across the country modelled like Gravity – promoting sustainable, ethical fishing. It’s a shift, changing local fishermen from passive observers, agreeing to the absurd terms and conditions of corporates, to instigators transforming their own backyard. “And we’re getting there. We’re showing what can be managed from the grassroots. It’s pretty simple. If you look after the fish stocks, there’s no need for fishing quota at all. Fishing management should be managed by fishers.

Those doing the mahi, those on independent boats, the people most connected to the fishing industry – those are the folk we need to be listening to. They understand the importance of connection to our wild food resources. I need to know the system inside and out if I’m going to make a change. I find out where the door keeps shutting and go back to that door over and over and over, but I know we’re going down the right avenues because I keep finding people who do want to help.

A Gravity model means fishing closer to home, and in turn, fewer logistics and freight, while providing more accessibility and affordable kaimoana for locals. You could drive down to the wharf and get it and create a connection with the fishers. There are wins all the way through. The fisher makes more, the chef gets a little extra margin, and the customer is engaged and connected with the wild resource on their plate, the people who fished it, and the place from where it came. When you start to add lots of little, you start to have a price range that helps. It would look like a green light for infrastructure and working to obtain quota for specific management areas. That way a certain percentage of fish would stay in the region. It’s about feeding and nourishing the community first. This new future offers job opportunities on a mass scale, not just for a single company in a single concreted floor factory, but across the board. Communities will spawn new ideas: smokers, butchers, people transforming the byproducts of byproducts. Think of it as big scale smallness.”

Seven parts make up the model Nate is proposing in each region:

A packing facility with a food safety plan and Licenced Fish Receiver Certificate.

Access to an existing target market which includes direct to both hospitality and end eaters in New Zealand.

An online ordering platform to receive orders and creates invoices.

A logistics team which understands fresh fish.

‘Know your Eater’ programme, including social media, other marketing, and general business management.

Mixed fin fish quota based on abundance in each regional sector.

Education about harvesting including techniques, preservation, packaging.

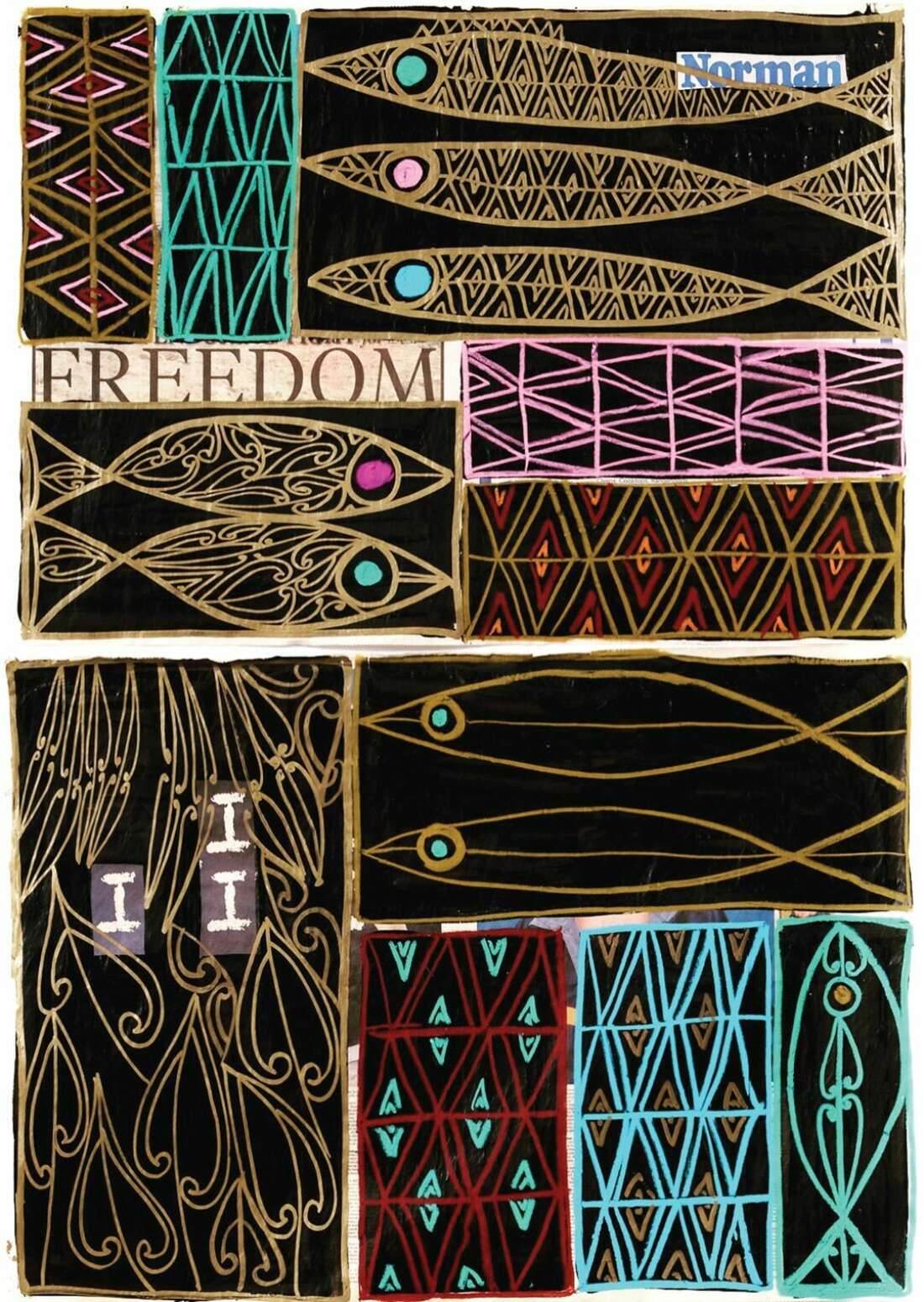

Words by Nate Smith as told to Louise Evans. Artwork: Norman Freedom III by Tracey Tawhiao