Category — Travel

Kumamoto

Saturday

7:10am, Haneda Airport. Outside is a thick vichyssoise grey fog that bleeds seamlessly into the sea.

We take off into the soupy air, shadows of freighters and fishing boats hanging in the murk below. The plane banks sharp to the left and we pass over the square edges of the Boso Peninsula, an industrial mirage of smokestacks fading in and out of cloud. We’re climbing fast: already a plane coming into land is tiny and swift beneath us.

We’re going to Kumamoto.

———

9:00am, in the sky over the island of Kyushu, Japan’s fourth-largest and southernmost major island.

A wild land, refuge of religious exiles and the last vestiges of the samurai, and yet, due to its proximity to mainland Asia, also one of Japan’s main points of trade with the Chinese, the Koreans, the Portuguese, the Dutch, before the shogunate closed off Japan’s borders to the outside world.

It’s a stretch to say Kyushu is shaped like a belly, or even any part of a human torso, but somewhere I’ve heard Kumamoto described as “the belly button of Kyushu” and picturing the curves and folds of peninsula and bay that form a layer of protection between Kumamoto and the East China Sea; the description sticks.

We descend over rugged forested mountaintops, tiny terraced hamlets nestled between steep slopes. An impossibly jagged peak piercing the wispy cloud. A river widening across a flat, alluvial plain. A cluster of volcanic hills jutting out to sea. A river snaking through the central city, flanked by high rises, and in the midst of it all, the landmark, Kumamoto Castle, heavily damaged in last year’s 7.0 earthquake, cloaked in scaffolding.

———

4:00pm, in one of the many covered shopping arcades that crisscross the city.

We’re here ostensibly for the purpose of tracking a bear. The kanji for the kuma in Kumamoto means “bear” in Japanese, and Kumamoto Prefecture’s world-famous mascot is a rotund black bear with rosy red cheeks and a penchant for mischief and antics, and the real reason for this trip.

But I’m more interested in a red shoebox-sized light hanging outside a dark stairwell on one side of the street; it reads, simply, “Wine Bar”. I had a hunch before that this might be a city with a good natural wine scene, vaguely recollecting glimmers of interest passing through my Instagram feed some months or years before. I have no expectations: for now, we’re on a bear hunt.

———

9:30pm, at a tiny bistro with a killer playlist.

The owner-chef can’t be any older than I am, I think, though that’s not saying much these days. He has mostly French bottles open that day, so we drink a minerally-sweet chardonnay and something else, something red, I try to write down but I’m distracted by the menu: handwritten in tight, angular script on a notepad with most of its pages ripped off, it’s a list of Kyushu’s greatest unknown hits. Fritters made with Oita whitebait, from the other side of Kyushu. Marinated Nagasaki squid. From Kumamoto: flash-sauteed Spanish mackerel from Tanoura to the south, a cheese platter from Tamana Farm in the north. And from the Amakusa islands that jut out from Kumamoto to the sea, a thick, tender cut of sea bream, braised with a walnut-miso sauce. None of it feels put on; none of this smugness you can often get in farm-to-table dining in the big cities; here it just feels like a shrug, an afterthought so obvious it’s not even worth pointing out. Of course everything is local. Why wouldn’t it be?

We eat a salad and I try to write down the songs that keep coming, one after another, a jaw-dropping procession of obscure bangers but I’m too overwhelmed by the wine and the food and in the end I’ve only managed to scrawl the name of what, upon later Googling, turns out to be a Korean psychedelic singer from the 1970s.

After the meal, everything blurred by now, I ask the chef for something sweet and he pauses for a moment, comes back with a bottle in hand. It’s a clear bottle, unadorned except for a small golden gourd-shaped sticker that says, simply, in timid handwriting: Super Dela-x. A cloudy yellowish white, bursting with the sweet frustration of bruised fruit, beguilingly thick and heady, bubbly and deep. I’ve never thought of myself as someone who’d describe a wine as exhilarating. It’s exhilarating.

He tells us the grapes are Delaware, from Yamanashi, but it’s a limited collaboration between a local wine shop owner and the local producer, Kumamoto Wine. Only a handful of bottles were made. I want to ask for another glass but it’s late, he’s closing up, I don’t want to be greedy.

———

11:00pm, upstairs in an unmarked bar on the third floor of a plain concrete building.

Our man at the bistro has drawn us a map of the neighbourhood on a piece of notepad and it’s led us up a suspiciously tranquil stairwell to a plain wooden door with a tiny peephole. I peer through. To our Tokyo eyes there’s an inordinate amount of space. We sit at the bar overlooking the window and watch the people (very few) and cars (even fewer) and drink whiskey very slowly. The quiet is delicious. Before leaving we’re given a couple glasses of water and I notice that even the tap water in this city tastes like a dream.

Sunday

5:15pm, on a slow, clattery train taking us back up the coast from Amakusa to Kumamoto City.

I’d read in a brochure earlier that the Amakusa region is famed for its wine-coloured sunsets and I’d brushed it off as a bad translation job by an overzealous local tourism board. The train has lulled us to sleep but we wake up just long enough to see the sun dipping below the Ariake Sea; and it’s true, the sky is an impossibly moody hue, orange fading into a deep wine-red maroon. I think about that sign. Wine Bar. I think about rose and orange wine and temperamentally bubbly reds. I drift back out of it.

———

9:45pm, at an izakaya upstairs in a rustic wooden building with a grandfather clock.

The place doesn’t feel like a natural wine bar but we’re here on a tip from a friend and sure enough, next to the towering sake and shochu bottles there it is: a fridge full of wine, mostly local, mostly natural.

But that’s not the surprise: it’s that here, too, we’re eating exclusively locally, without any fanfare. Seared slices of kabosu-buri sashimi from Oita, where they raise the yellowtail on feed mixed with the green peel of the kabosu citrus for which the prefecture is renowned. We’re given salt and kabosu chilli paste and a couple of halves of the compact green fruit itself for seasoning the buttery-soft, sweet fish. Amakusa octopus and mikan oranges marinated with tomatoes grown locally. Amakusa bainiku pork, meat from pigs raised on plums, ribs charred and sticky and melting from the fat and the heat and the miso marinade. Even the oyakodon we have to close off the meal is made with local jidori, one of sixty-four heritage breeds of free-ranging chicken that are raised to strict regional standards; the rice underneath is from the Aso volcanic plain east of here.

I find myself thinking the menu is disproportionately skewed towards local food but that can’t be right, this is backwards city thinking. Because isn’t it the way it should be? If you’re blessed with abundant water and fertile volcanic soil and rich marine life why would you look anywhere else for your food?

———

12:15am, across the street from the now-glowing Wine Bar sign.

I love a good late-night bookstore. I’m out of cash or I would have bought the beautifully illustrated book explaining the seventy-two seasons of Japan. I regret that I’m too tired for Wine Bar.

———

1:00am, in the hot spring at the hotel.

Out of the bath, I notice a sign next to a drinking fountain that proclaims Kumamoto has been named by the United Nations as a best-practice city for groundwater management; all of the water for Kumamoto City comes from underground aquifers formed by pyroclastic flows from ancient eruptions of nearby Mt Aso and continues to supply the 730,000 residents of the city with clean, natural mineral water. Of course everything tastes so good here. Of course.

I drink a metal cupful before bed. It’s ice cold and softly sweet and I wonder what crap I’ve been drinking in bottles all this time.

Monday

8:30am, at the buffet breakfast in our hotel.

Cured ham made from local basashi (horse sashimi). Octopus carpaccio, from Amakusa, again. Sweet, heavy Aso milk. Of course, the usual suspects are here – rice, miso soup, pickles, salad bar, eggs. But Kumamoto is surprising me, even here, in this chain business hotel.

———

4:55pm, back in the shopping arcade.

We’ve caught the tail end of some sort of market. We gulp down some more creamy jersey Aso milk sold in little bottles from a farm stall. I wonder if this is what milk used to taste like? It’s rich and heady, reminiscent of vague, deep memories of a farm.

———

10:30pm, on the street outside the teishoku-ya the quiet-genius chef from the first night recommended us.

We’ve spent too long drinking beers and eating confit chicken giblets served up by the long-haired manager of a hushed craft beer bar tucked away in an office building and now we’ve walked up the stairwell here to find it’s too late – he’s closing up.

I have no cash. We head to look for an ATM. I tipsily promise to book myself flights back to Kumamoto so we can come eat here one day. I don’t even know anything about the place.

———

11:15pm, down another lane nearby.

We’ve found somewhere to eat. It’s an okonomiyaki place, it’s still open, we’re hungry. Okonomiyaki isn’t a traditional Kyushu food so I’m not expecting anything like the previous two nights, but we order a vegetable platter on the side and the chef starts carefully placing a halved red onion, sliced carrot, a bit of sweet potato, on the hot teppan in front of the counter. All from Aso, he gestures as he gradually adds shiitake, radish, edamame, capsicum, endive, shishito peppers to the sizzling surface.

We’re drinking something sparkly and chatting with the chefs, just a bunch of really nice guys, and while one of them carefully cooks our okonomiyaki the other comes around the counter to our seats, he’s grinning, holding out a bottle of a Côtes du Jura Savagnin: are you after a second glass of wine? I’ve been wanting to open this one.

It’s a deep, viscous yellow, with a hint of oxidation and a smooth pull of something that eludes me to the point of happy, wine-soaked tears.

I’m getting emotional. But the story’s not over yet.

———

12:30am. Wine Bar.

We’re fast approaching one in the morning and we have an appointment at the Kumamoto Prefectural Government offices in a few hours but it’s our last night here and I’m in the surprise grip of an immense love and respect for this city I hardly know but that feels like the kind of instant friendship that happens when you meet someone who doesn’t try to be anything but themselves.

So we head up the stairs past the red-lit sign. Brush past a group of salarymen – somehow more relaxed, jovial than their Tokyo counterparts – on their way out. The bar is dark, moody, something out of an imagined eighties whiskey scene. There’s a massive flower arrangement in one corner, a tangled mess of branches and blooms. A couple of miniature grey tetrapods – those geometric concrete breakwater structures found all over the coasts of Japan – on the counter next to a row of empty wine bottles.

And there it is. A clear bottle plastered with a dozen-odd of those gourd-shaped Super Dela-x stickers. My heart rate picks up. I lean forward.

Sorry, the owner laughs. We had our third anniversary party here the other night, the whole case is gone. But if you really want to try it before you go – what time’s your flight tomorrow?

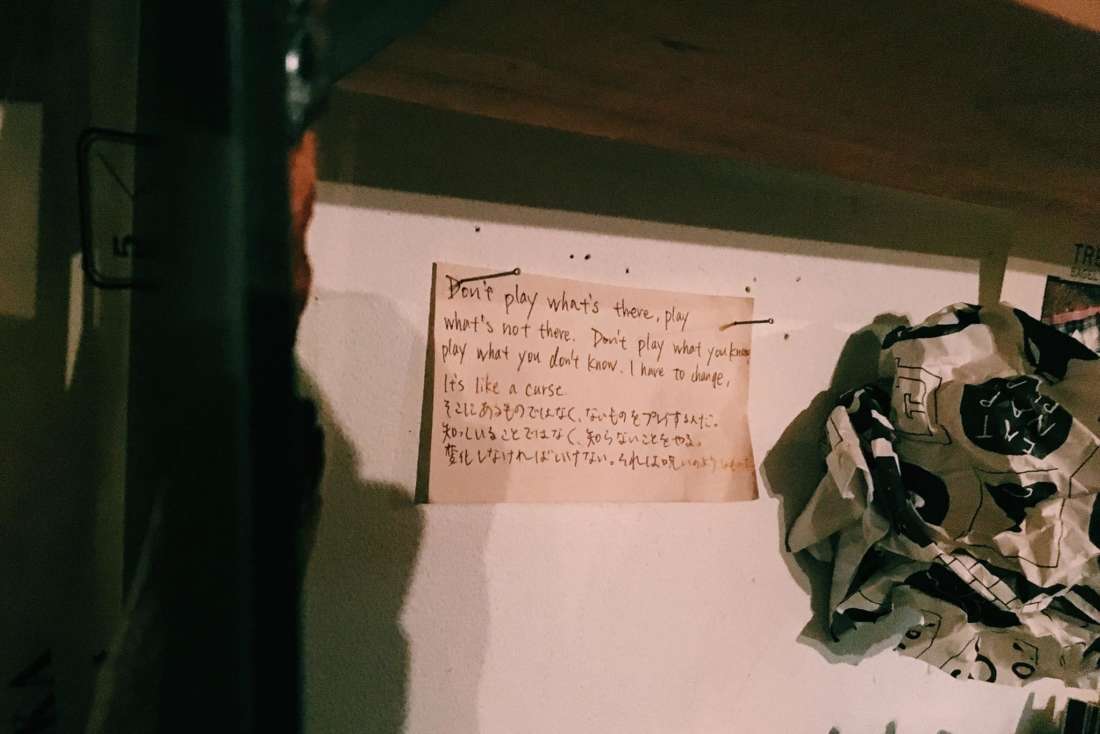

I’m sheepish: I had a glass my first night here, I’ve been looking for it ever since. He laughs again, shakes his head at me: this kind of thing is only meant to be a one-off.

He pours us Kumamoto chardonnay and a juicy French Pineau d’Aunis and glass after glass of tap water as he tells us stories about his hometown, ten minutes south on the Shinkansen, where every November for four hundred years they’ve marched a 200-kilogram half-snake, half-turtle float down a shallow riverbed. We promise to return.

We exchange Instagrams and I gulp down one last glass of water.

———

2:30am, walking back to the hotel.

Somehow we’ve ended up here, in Kumamoto, in the belly button of Kyushu.

At first glance Kumamoto is just another web of endless covered shopping arcades, clusters of ageing concrete buildings that are the hallmarks of the mid-sized Japanese city. Pleasant enough, but nondescript. A more callous person might say forgettable.

But there’s plenty to admire about the place: the rich samurai history, the fierce local pride in its trademark cuisine – strong, assertive dishes like horsemeat and eyewatering karashi-renkon, lotus root deep-fried with Japanese mustard, the intensely garlicky, creamy tonkotsu ramen.

After three days in the city, though, I’ve forgotten about all that. I’ve even forgotten all the statistics I’d researched on earthquake recovery, the countless videos I’d watched of a fat, costumed bear-mascot sliding down stair rails and falling off Shinkansen. All the bowls of Kumamoto-style ramen I wanted to eat. Instead I’m just buzzing on good wine and honest local produce and the certainty that sometimes that’s all you really need from a place.

———

3:00am, at the hotel.

I’ve made the mistake of almost falling asleep in the sauna upstairs. I’m lightheaded. Tomorrow’s a big day. I drink three metal cupfuls of cold, sweet Kumamoto tap water and crumple into crisp hotel sheets.