Category — Features

Embrace Rampancy – How PermaDynamics changed my life

“If you’re holding a sapling in your hand when the Messiah arrives, first plant the sapling and then go out and greet the Messiah.”

The Overstory. Richard Powers

Are any of you familiar with the feeling of your whole worldview being turned upside down? An epiphany that a craft you feel competent at, and have dedicated years of practice to (and most of this volume of Stone Soup), may in fact be almost entirely misguided.

“Embrace rampancy!” These are the two words declared by Klaus Lotz early in our Syntropic Food Forest Course that had my synapses reaching for new connections like mycelium beneath a forest floor. It doesn’t really sound like a radical proposition, except they were spoken in celebration of gorse. GORSE?! You don’t have to look far to find a farmer who is at war with gorse, and the only farmer in our midst experienced with fighting this invasive species was visibly dumbfounded – ‘Are they seriously suggesting it would be better to purchase land with gorse than with pasture?’ But we were surrounded by the undeniable evidence that Klaus was not as crazy as he seemed.

It sounds melodramatic, but there was life before PermaDynamics and life after. Some of the amazing growers I know might take offence, but I’m going to say it: the rampant abundance created by Klaus Lotz, Vanessa Keegan and their children Frida and Josh — from their verdant perennial paradise in the middle of the burnt earth of a Northland drought — eclipses anything I’ve ever witnessed.

syntropy

[ sĭn′trə-pē ] n.

The psychological state of wholesome association with others.

A number of similar structures inclined in one general direction.

I’ve been growing vegetables for almost twenty years, as and where I could: inspired by my mother and her mother, and out of necessity when confronted by a second child on a photographer’s assistant income. In the spring of 2012, energised by a desire for food sovereignty in the wake of the GFC, I progressed from a small garden bed at the front step of our recently purchased home, to digging up every available inch of the 360m2 site and turning it into an edible landscape that we refer to as Arch Hill Farm. I felt pretty proud of my little urban oasis: an emblem of urban agrarianism, hoping to provide inspiration to passers by in the middle of the city. But apart from half a dozen disjointed fruit trees, Arch Hill Farm has been dedicated to annual crops. You know, those plants that make up the bulk of our diet — whether staples like wheat, rice or legumes; or favourites like tomatoes and eggplant — but require that we replant them every year. That’s how you grow food though… right? Make compost in autumn, sow seed in spring, nurture with water and fertility, enjoy abundance through summer and autumn, repeat, repeat, repeat, ad infinitum.

Perhaps syntropy and I were destined to meet. There were a few early signposts to my turning away from annual plants along the way: the pleasure I’ve taken from planting many trees over the years, on mine and the council’s land; the avocado trees I’ve planted in a nearby reserve; the olives I’m the only person to harvest from our street; the walnuts I beg to be sent north by a family friend; a favourite parable, The Man Who Planted Trees by Jean Giono, bought as a gift by my wife almost twenty years ago – an illustration from which inspired a tattoo to celebrate gardening and sharing.

A couple of years ago a short documentary called Life in Syntropy (available on Youtube and Vimeo) popped into my algorithms, illustrating a dynamic visionary Ernst Götsch rehabilitating thousands of acres of the Amazon while producing an abundance of food, including the most sought after cacao on the planet. The prospect of a life climbing trees and eating bananas, I was pretty inspired and shared the video with everybody I knew. Food production in harmony with rewilding: he seemed to have a roadmap to rehabilitate our agricultural relationship with the earth in addition to his piece of land. It wasn’t long before I got wind (through a Radio NZ interview) of one of his disciples climbing trees and growing bananas in Northland, which I filed away in my list of things to learn more about later.

In hindsight, I was already walking down this path without fully understanding where I was headed. Through my involvement with OMG Organic Market Garden in Auckland I’d heard Sarah Smuts-Kennedy tell the story of photosynthesis and soil life many times (which you can read at the beginning of this issue). I’d been watching it put into practice with the biointensive companion planting of annual crops by Levi at OMG, and had started applying the principles at Arch Hill Farm, which resulted in much greater abundance.

This journey led me back to my list, to finding PermaDynamics on Instagram and pondering their Permaculture Design Course. When I eventually tried to sign up, it was full: a good sign, maybe next year, but how about something to feed the interest in the meantime? I gathered a small crew of my Stone Soup family and signed up for their two day Syntropic Food Forest course.

Literally the week before attending the PermaDynamics course, I stumbled across an article called What If We’re Thinking About Agriculture All Wrong?, which called into question our annual agriculture with stories of two farmers, in Greece and the United States, who grew in polycultural systems abundant in perennial staples like acorns and chestnuts in addition to a multitude of other fruits, nuts, berries and animals. That’s how I discovered Mark Shepard and his Restoration Agriculture. Mark only eats food from perennial crops, stating that “our planet looks like it does because of how we get our food”. He challenges any of us who proclaim to have a local-non-industrial-diet to attempt to do the same, and if we can’t, then it’s Industrial Ag providing most of our calories. To paraphrase his logic (available in his book Restoration Agriculture, one of Klaus’s suggested readings): why work endlessly in a never ending battle to maintain fertility; making compost, sowing and nurturing plants that are essentially weeds looking to cover bare soil. “Where are the annuals in nature?” asks Kalaus, “in places of disruption”. Annuals are pioneers that are the first succession in earth’s desire to become a forest. Does it make sense to work so hard to maintain a disruption with this first succession, when instead we could create a forest that in Klaus’s words is “so abundant that it throws food at you”; that creates its own fertility by feeding the soil through photosynthesis, and compost with a little help from pruning (chop and drop); and never needs planting again. Have we in fact — for the last ten thousand or so years — been thinking about agriculture all wrong?

It’s amazing to see in PermaDynamics a modern example of an abundant diverse agricultural system in this country which — in common with indigenous wisdom — seeks to embrace and collaborate with the generosity of nature. A system that takes no inspiration from the European lens and its accompanying enlightenment desire to control and dominate. It opens a whole new realm of possibility from which to transcend our recent relationship of attempted authority over the land. A realm in which we give more than we take, to the soil, the surrounding ecology and each other; while massively increasing the diversity and nutrient density of foods we produce and eat locally.

You don’t need a lot of land to start this journey, you can do so in an urban backyard, around just one or two fruit trees, one guild at a time, thanks to the advice which follows from Frida.

Me personally? Klaus told us, “life is a dynamic which runs against entropy”. So I’m running for the hills in search of a piece of land upon which to be a peasant, where I can dedicate the rest of my life to syntropy. Although unlike Mark Shepard, I’m likely to cede a sunny little corner to tomatoes, chillies, eggplants… and my favourite: sunflowers.

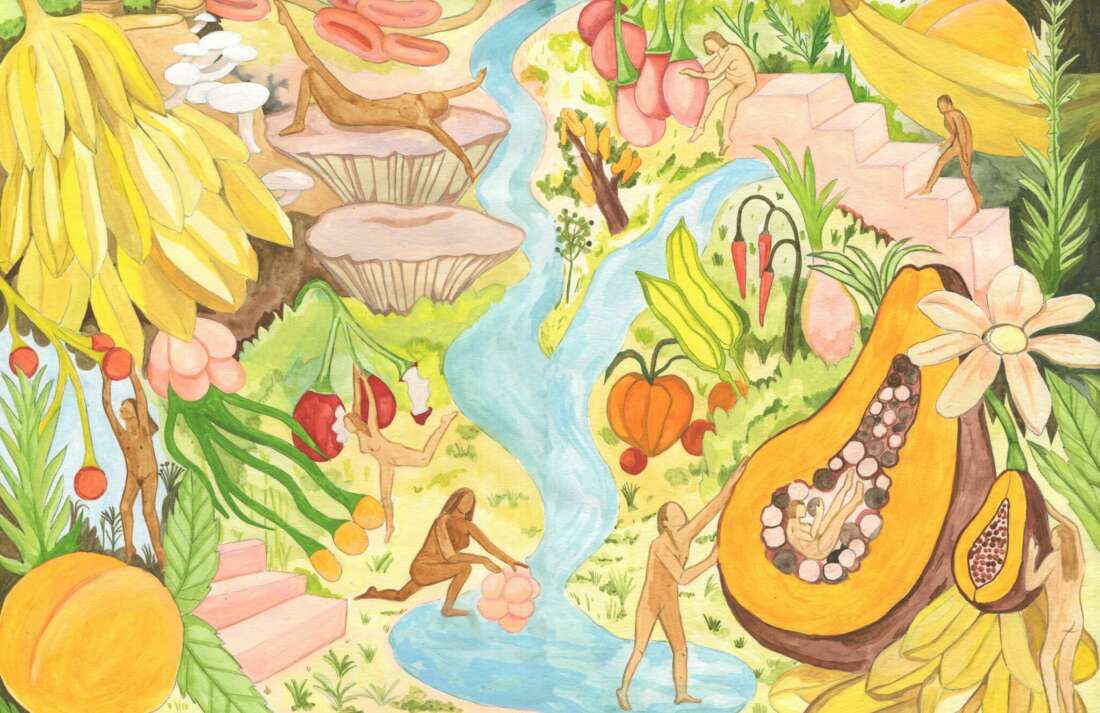

Illustration: Lilly Paris West