Category — Features

Te Mahi Oneone Hua Parakore: A Maori Soil Sovereignty and Wellbeing Handbook.

What would Māori health and wellbeing look like from the viewpoint of soil?

Taking the indivisible relationship between tāngata and whenua as our starting point – and, by extension, oneone (soil) – this book shines light on the whakapapa relations between Māori and soil, the many different names Māori use to describe this elemental wonder, and its deeply connective relationship to the everyday needs of tangata whenua, at individual, whānau, hapū and iwi levels.

Soil is, and always has been, a very desired and contested taonga both in colonial times and under more contemporary globalised conditions. Existing scholarship tells us much about the environmental and economic challenges facing this treasured resource. This volume turns the tables on understanding soil as an economic resource to understanding soil as part of the interconnected universe that makes up Indigenous realities in Aotearoa. This book champions soil as a taonga that we must look after to ensure the wellbeing of our whānau, communities and Aotearoa. We argue that enhancing soil wellbeing contributes to the wellbeing of whānau and communities in general. Subsequently, the book also contains practical steps that can be taken to contribute to greater wellbeing for soils and peoples.

This book also builds upon the themes explored in Te Mahi Māra Hua Parakore: A Māori Food Sovereignty Handbook and the hua parakore framework itself, which is a Māori food sovereignty approach and a kaupapa Māori verification scheme for Māori organic growers. It was developed by Te Waka Kai Ora (National Māori Organics Authority) through a three-year kaupapa Māori research project that engaged with Māori organic growers, farmers, whānau and rongoa practitioners. Hua parakore is a kaupapa Māori framework and, like all frameworks, it can be applied in multiple ways. At the heart of it, as the first book explains, are the six kaupapa: whakapapa, wairua, mana, māramatanga, te ao tūroa and mauri. These kaupapa are interconnected and are drawn from mātauranga Māori and serve as pillars to guide Māori food-growing practices and food politics. Te Mahi Māra Hua Parakore is an introduction to the politics of Māori food sovereignty as well as a practical guide to growing hua parakore kai. This current book follows on and applies the hua parakore or Māori organics framework to soil and soil sovereignty. It is a continuation of Indigenous thinking in relation to hua parakore, soil and wellbeing.

Accordingly, Te Mahi Oneone Hua Parakore gathers kōrero from a range of Māori experts in order to elevate the mana of soil by understanding it as fundamentally linked to whakapapa, tūpuna (ancestors), rangatiratanga (sovereignty) and hauora (wellbeing). We ask: how might a soil-based viewpoint shine light on how to practise, enjoy and struggle for more connected, resilient and healthy lives? What skills can we, as whānau, hapū, iwi, Māori, and national and global citizens, practise and share to offset the negative impacts of industrialised agriculture, climate change, globalisation and increased urban living? How might deepening and diversifying understandings of soil help to clarify its role as a connective tissue to wider systems of exchange, including financial, cultural, political and economic systems? How can soil, as a kaupapa Māori narrative, generate, sustain and nurture the multiple life worlds of Māori who depend on this relationship? This book seeks to explore these questions and is organised in two parts: frameworks for understanding and a showcase of soil heroes. We also include a series of recipe cards in the back sleeve of the book.

Part One:

Frameworks for Understanding te Mahi Oneone Hua Parakore

In Part One, we offer intellectual and cultural frameworks for understanding the relationship between soils and peoples. Jessica Hutchings and Jo Smith begin this section with some reflections on how the kaupapa Māori organics framework can provide a guide for living beyond the fractured, industrialised food systems that surround us. Connecting with our divine senses and the wisdom of our tūpuna, including the knowledge found in soil, the chapter draws on some of the mātauranga from the Māori organic community, Te Waka Kai Ora. The chapter also draws from Jessica Hutchings’ longstanding Hua Parakore growing experiences to offer six values and principles for developing a kōrero of Māori soil health and wellbeing.

Senior Māori environmental scientist Garth Harmsworth’s chapter explains how health and wellbeing (hauora, whaiora, oranga tonutanga) is based on whakapapa connections to soil through the maintenance of key values such as mana, mauri, tapu and wairua. He argues that, to understand these origins and links between soil health and human wellbeing, we must start with the beginning, with Ranginui and Papatūānuku, and the stories of progression

and creation.

In Jessica Hutchings’ chapter on soil sovereignty, she advocates for the rights of soil and its fundamental connection to food sovereignty issues. Speaking up for soil, Hutchings offers a food sovereignty activist framework for understanding soil–people links. Horticulturist, ethnobotanist and Māori resource and environmental management expert Nick Roskruge provides additional insights on the whakapapa connections to whenua through the lens of horticulture and naming practices that contribute to a soil taxonomy. He argues that while there are fundamental whakapapa relationships to soil as an element of Papatūānuku, we can also liken soil to a supermarket, supplying all that we need, and that it is a crucial actor in our food system.

Part Two:

Oneone Ora, Tangata Ora: Māori Soil Heroes

The kōrero gathered in this section draws on interviews by kaupapa Māori researchers with a number of oneone ora, tangata ora heroes who work in Māori communities, kura and marae to elevate the mana of soil. Organics advocate Maanu Paul shares his long-term goal with Kiri Reihana Spraggs: to get our soil, being Papatūānuku, into an organic state, a Māori state, a natural state. If we want to grow a māra kai, he argues, we have to learn to read the land, the wind, the stars, the moon and the tides. Teina Boasa-Dean and Ruth Nesi Bryce discuss the Ngāhuia Lena gardens and the whānau organisation that has nurtured, tilled and harvested māra kai at Rūātoki North, Tāwhia and Waiōhau in the northern and western sections of Ngāi Tūhoe rohe (district). This chapter includes a karanga composed by Ngāhuia Lena Hare, which celebrates the microbial life forms in soil and the intertwined whakapapa of human and non-human life forms. Hōhepa Hei, kaiako at Te Wharekura o Maniapoto in Te Kūiti, talks to Yvonne Taura about the project-based learning techniques he uses to convey the responsibilities of kaitiakitanga to rangatahi. These projects include building and adorning a carved pātaka kai, establishing māra kai and a native nursery, and learning harvesting techniques. Through such projects, rangatahi learn about the importance of soil

health and the interconnected realities of having a kaitiaki relationship with te taiao (the environment).

The section continues with Antoine Coffin’s account of Ngāti Kahu hapū gardening traditions at Te Wairoa, where he demonstrates the positive relationship between growing and eating your own fruit and vegetables, as well as the long-term health and economic benefits it generates for households. Helen Potter shares the story of Rueben Taipari and Heeni Hoterene, who live with their whānau on ancestral whenua in Ahipara in one of three whare uku they’ve built there: homes not just built on ancestral whenua but of the whenua itself. Homeopath Renée Perkins talks to Jo Smith about how connecting to soil means connecting to te taiao, and the wellbeing that can flow from such exchanges. For Renée, homeopathy is a system of healthcare that flows from the law of similars where like meets like. Sharing her own experience of coming to homeopathy, Renee’s kōrero demonstrates the range of possibilities we have for thinking about healthcare, and the links between mātauranga Māori and healthcare movements from further afield. Hineamaru Ropati talks about her role in supporting the dreams and aspirations of the kaumātua who established the urban-based Papatūānuku Kōkiri marae in South Auckland, and the role soil plays in bringing communities together. Kiri Reihana Spraggs talks to Māori science scholar Hema Wihongi about her views on soil, which is a continuation of the kōrero that drove the Wai 262 flora and fauna claim lodged in the early 1990s. Finally, Gretta Carney explains how the Hapī Clean Kai Co-Op, based in Napier, works to produce healthy organic kai for diverse communities, with an intent to nourish and heal. Gretta’s homeopathic journey has taught her that disease thrives in complexity and that hauora is always about simplicity. Hapī aims to keep kai simple – the collective is also focused on sharing knowledge to enable the flourishing of hauora for all. Hapī believes that kai is transformative and that the prevailing and detrimental norms of chemical preservation and fertilisation in food production must be combatted by hauora-generating foods that connect with communities. Gretta’s recipes can be found in the back sleeve of the book. The recipes underscore the link between oneone ora, tangata ora in our every day.

Book excerpt courtesy of Freerange Press

You can purchase Te Mahi Oneone Hua Parakore: A Maori Soil Sovereignty and Wellbeing Handbook online at:

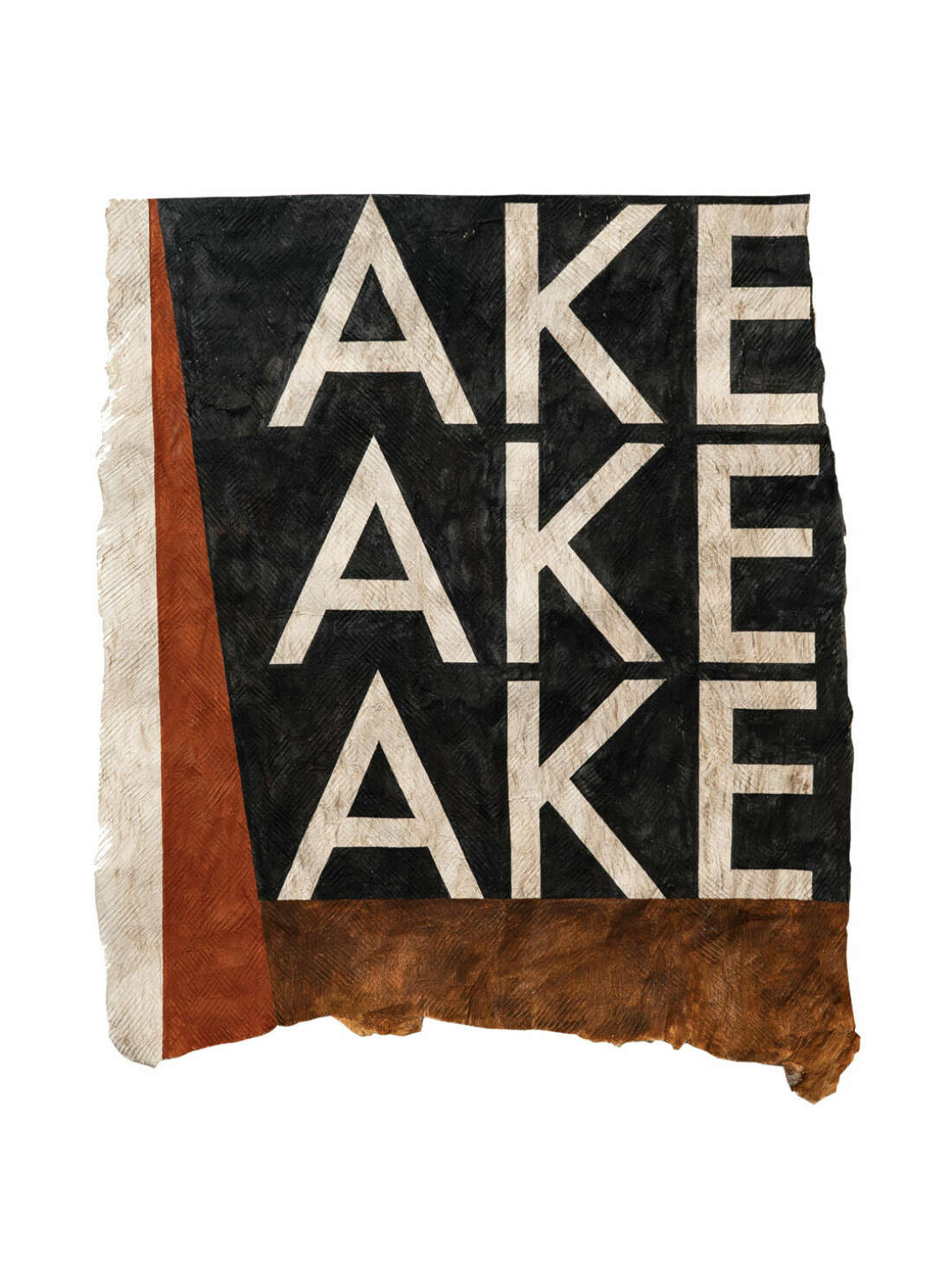

By Jessica Hutchings and Jo Smith. Artworks: Nikau Hindin