Category — Features

I once had an office in a flour mill.

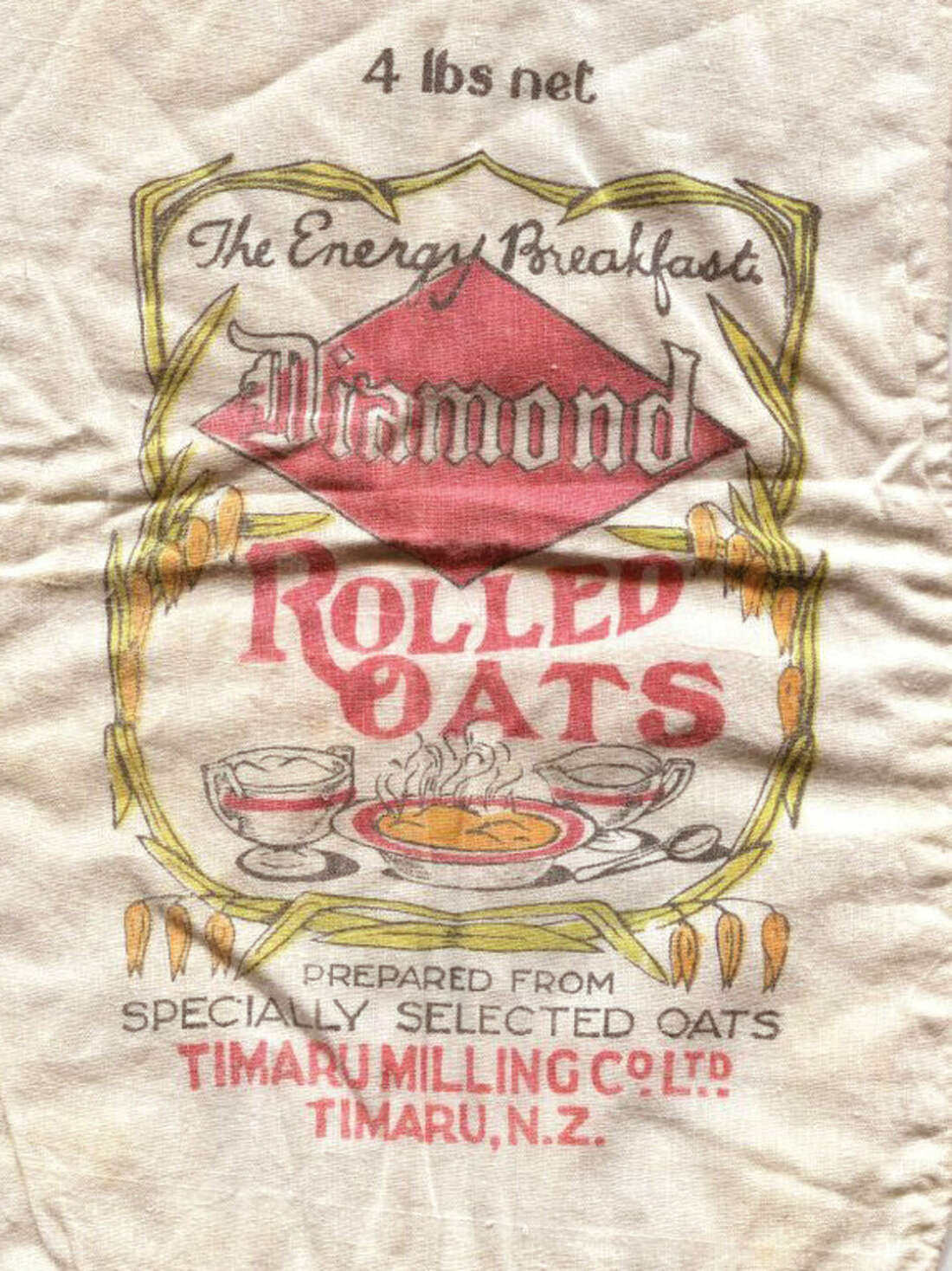

My flour journey began at Timaru Milling Company nearly thirty years ago, during a year-long secondment in a technical support role for factories using flours from wheat, barley, corn and oats. Built in 1882, Timaru Milling was the first in the country to be equipped with roller mills, and it was later the site for the manufacture of Diamond Pasta. The other factory, Flemings Creamoata Mill in Gore, began as an oat mill in 1893.

The learning curve was steep, across activities on both sides: growing and processing the grain and then transforming it into locally made pasta, porridge oats and snacks; agronomy trials for new varieties that were being run in conjunction with Crop & Food (now Plant & Food Research); the nutritional profile of the edible product; and the assessment of the land and plant species which were best suited to the local climatic conditions across North Canterbury, North Otago and Southland. But more than that, it was a brief taste of the vagaries of farming and the commercial and consumer pulls towards not only sustainable practices but higher nutritional value. I can only now appreciate how hard it was to meet the exacting standards of consistent quality for which farmers were paid against.

A bit of history: New Zealand’s first flour mill, in Waimate North, began operation in 1834. Built out of timber and powered by a water wheel that was set in a small stream on the farm established by the Church Missionary Society. Auckland’s first flour mills were built in 1844 and by 1845, there were also three mills in Wellington, Nelson and Akaroa. Māori owned mills were established by the mid-1840’s in Waikato, Wellington, Taranaki and Whanganui to process the wheat they were growing. Between 1846 and 1860, there were 37 flour mills built for Māori owners in the Auckland province alone.

My interest in flour for breadmaking began nearly two decades ago when I had a wood-fired oven built and had been gifted a San Francisco starter from chef Dean Betts, along with numerous phone calls to Richard Tollenaar one of the former owners of Pandoro Panetteria, one of the first artisan bakeries to be established in Auckland, if not NZ. To be frank, I totally lacked the knowledge and skills back then to successfully bake bread other than pizza in the wood-fired oven. Fast forward to the winter of 2017, when it seemed like the whole world was learning to bake sourdough at home using the Dutch oven method, I took a sourdough class offered by Jerome Ožić, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Since then, I’ve become slightly obsessed with flour, particularly single origin flours from local farmers based in North Canterbury. The fear of running out of flour has me ordering ahead of depleting supplies. All this to fuel my sourdough baking. As a dietitian, I’ve been particularly interested in the nutritional value of these flours and am only just wrapping my head around some of the science behind long, slow cold fermentation and what this does to the wheat proteins, in particular gluten. Anecdotally, people with a wheat or gluten intolerance find that slowly fermented sourdough breads can be eaten without the same effects of loaves made with more refined flours, which do not undergo the same process. It is understood that this slow fermentation of up to 48 hours allows lactobacillus to modify and breakdown the indigestible amino acids proline and glutamine in the gluten. Sourdough however, is not gluten free and those with allergies and intolerances need to first check with their healthcare professional before trialing. I’d like to also make it clear that I am not a commercial baker so my experience is based on home-made sourdough using a method that closely approximates the Tartine method developed by Chad Robertson. I am in my fourth year of trial and error and still a novice.

In researching this article I have discovered that I am not alone in geeking out about flour. A growing number of chefs and bakers are looking for a closer connection to farmers who care about grains with provenance and sustainable growing practices which maintain the soil for future generations. Some bakers have taken this one step further by choosing to mill their own flour on a daily basis to ensure freshness and nutritive value. The onus is on losing less of the bran and germ which results in a flour of higher nutritional quality, flavour and a deeper colour in the resulting bread. In modern, larger roller-milling operations, these outer bran layers of the grain and the nutrient dense germ are removed and separated to become products of their own.

When selecting flour, Jerome Ožić considers whether it’s organic or biodynamic and adds, “a healthy soil with a diverse flora of nutrients and enzymes, gives the plant vigor and health. By not using toxic pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides, the plant has an opportunity to adapt to its surroundings. The plant has an intelligence somewhat. Very adaptable. When this is served, through rotation of crops, companion planting, and farming to nature’s laws, the plant has a harmonious life, able to withstand certain changes and grow to its capacity. This growing to capacity without the use of artificial additives gives the plant health. A healthy plant is a nutritious plant.”

The age-old technique of producing stone ground flour enables the bran, germ and endosperm to be milled finely together resulting in a flour which can be more than double the fibre content compared with normal retail flour; and predominantly omega-6 and polyunsaturated fatty acids, although the fat content is still low (around 2%). Key micronutrients are B vitamins (B2, B3, B5, B6 and B12), and vitamin E as well as calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, sodium, potassium, zinc and selenium. Both protein content and protein quality are of great interest to farmers and bakers. Both are affected by the nitrogen and sulphur levels and must be available to plants at the right rate and time during the growing cycle to benefit. Balancing nutrition and yield is the realm of farmers. According to Yara, “When managing the protein quality, the main aim is to get the plant to produce protein that contains the high molecular weight, long chain gluten proteins. Gluten proteins, e.g. gliadin, glutenin, albumin and globulin give wheat products unique extensibility and processing properties.”

Much of the wheat grown in NZ is to supply wholesale distributors and large scale bread companies. Of the 225 thousand tonnes of flour produced in NZ annually, only about 10% goes into retail flour sold in supermarkets for home baking.

When the country went into lockdown in late-March, and cafes, lunch bars and neighbourhood bakeries closed, home-based baking increased the demand for retail flour by 500% (source: Champion Flour Mills). There was never a shortage of flour itself, merely the demand for 1.5kg packs increased over and above what was a normal supply. Supermarkets were being supplied with pallets of 20kg bags of flour.

Most of our domestic flour in New Zealand is currently grown and milled by Champion Flour Mills. Established 160 years ago, it is now part of Japanese owned Nisshin Seifun Group of which flour milling is one its business units. Champion Flour Mills was split from the Goodman Fielder stable in 2013. It’s website states that, “Champion produces over fifty percent of New Zealand’s cereal based products, and exports to Australia and Europe. Champion has a deep involvement in a wide range of grain research and industry bodies. These organisations are committed to developing new types of nutritional grains, natural alternatives to chemicals, better yields, and championing and recognising industry and individual excellence.”

To date, Champion still supplies flour to Goodman Fielder, who retained the baking powder brand Edmonds, and it is the brand that has extended its range of baking ingredients to include retail flours previously held under the Champion brand. The current packs are printed with “Proudly NZ grown wheat” incorporated into the stylised map of NZ logo made up of sheaves of wheat. Milled from premium quality NZ wheat that is unbleached and “triple sifted to create a finer flour with a smooth, silky texture to ensure your best baking results”.

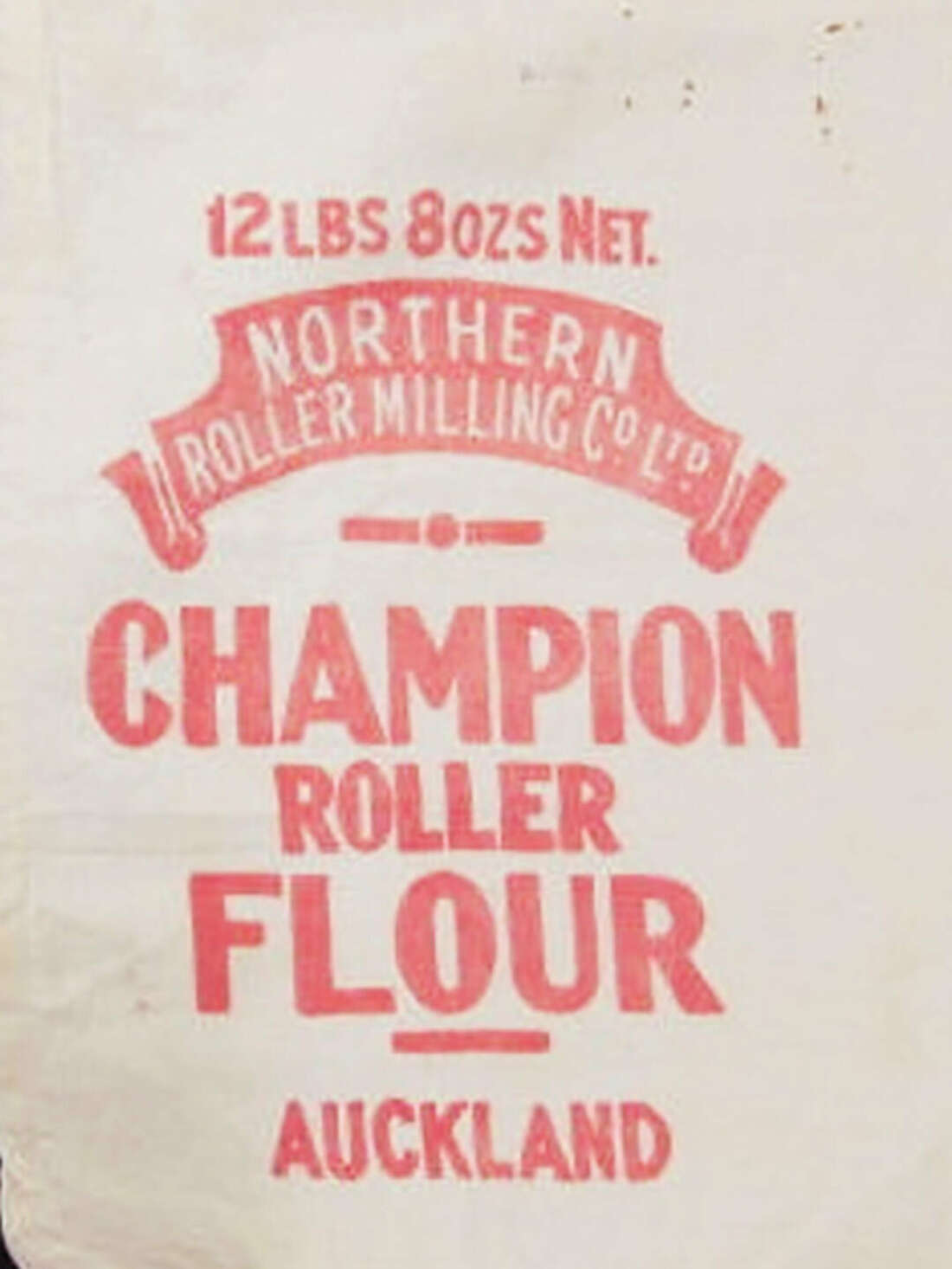

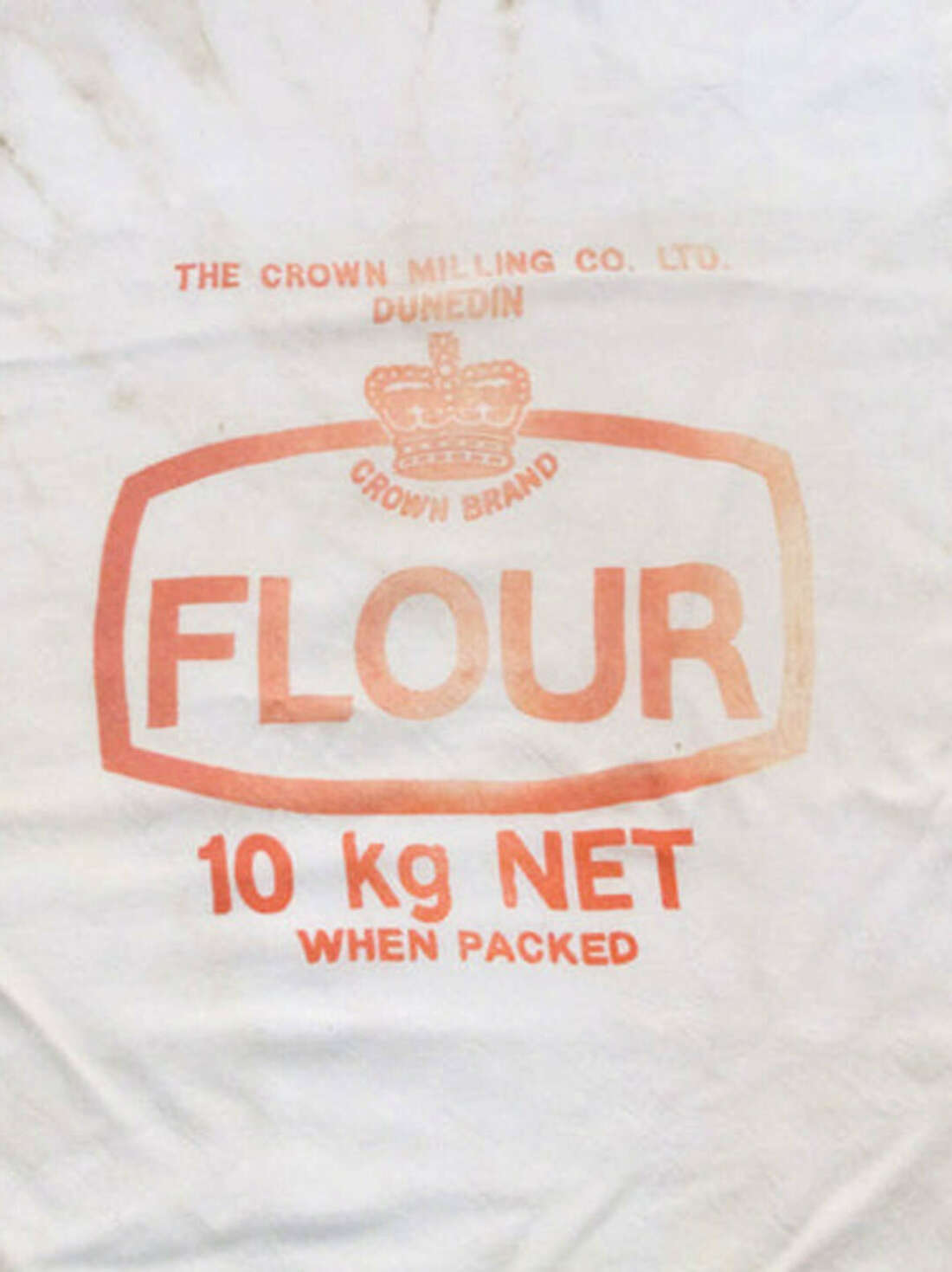

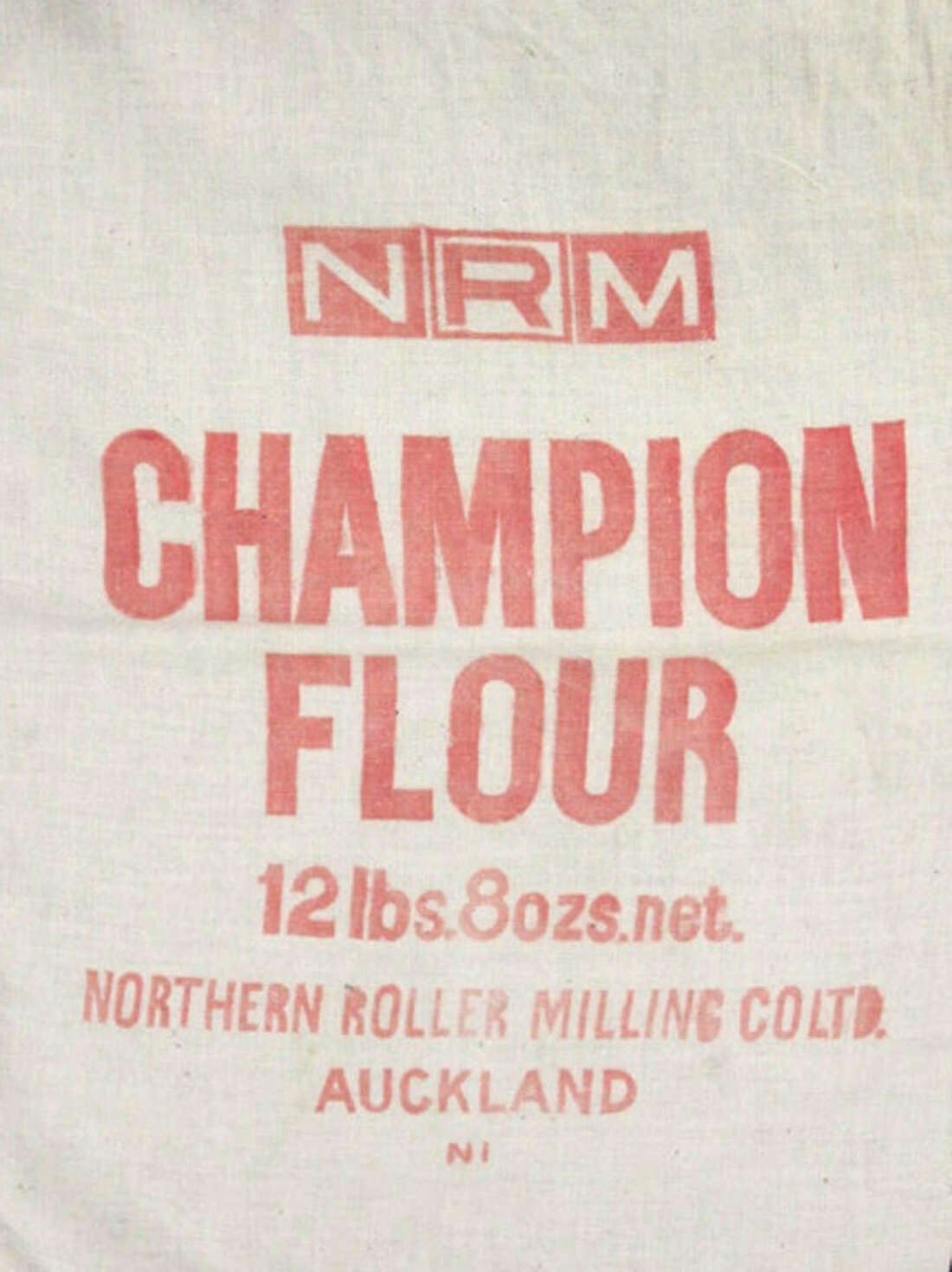

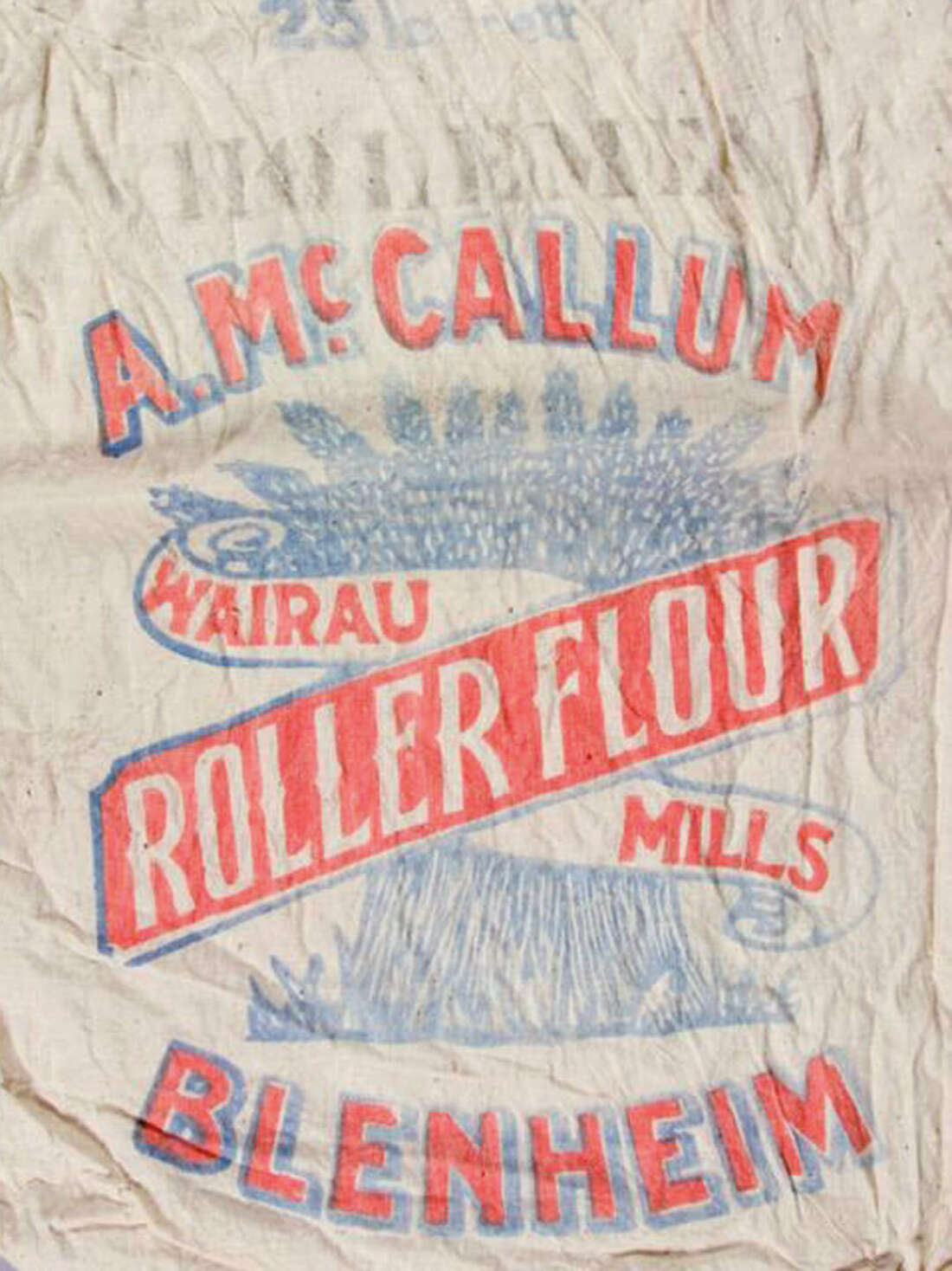

When I spoke to Paul Fahy, a miller of 43 years, technical and project manager at Champion Flour Mills, and current chair of the NZ Flour Millers Association (NZFMA) industry group, he recalled his years at Northern Roller Mill in Fort Street, Auckland; Crown Milling in Dunedin; Moorhouse Avenue in Christchurch; and South Flour in Invercargill. The NZFMA membership is made up of the four major flour millers in the country: Champion Flour Mills (Mt. Maunganui, Christchurch), Farmers Mill (Washdyke, South Canterbury), Mauri (Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch) and privately owned NZ Flour Mills (Tirau, Waikato). The flour produced is milled entirely from NZ grown wheat with the addition of specialty cereal grains for popular multi-grain breads such as Vogel’s and Molenberg; and for the most part destined for large commercial bakeries around the country. The flour is neither spray free or organic, however Paul is confident that growers maintain high standards of farming practices for arable wheat and cereals production, with good traceability.

Fungicide and herbicide application is undertaken sensitively. The Canterbury plains provide for almost perfect conditions for growing wheat – a record being set by an Ashburton grower achieving the highest yield in the world in July this year. Paul says, “Arable farming is very efficient on a rotational basis. Organic cereal production is challenging and requires proper crop rotation. Wheat is a huge depleter of nitrogen in the soil and unless managed well for example growing peas to nitrogen fix, prior to rotation with a cereal crop. About 1% protein is lost in the conversion of wheat to flour. High levels of protein between 13 -14% can certainly be achieved in the South Island. If there are 6 to 8 weeks of cool and moist conditions, the protein quality will be strong.”.

In the past, artisan bakers would struggle with the consistency of NZ grown wheat for producing European-style breads but with a growing interest in sourdough bread from retail artisan bakeries, chefs and home bakers, there has been an increasing demand for nutrient dense, high-quality flour sourced from small, local farms and mills such as Milmore Downs, Minchins Milling, Terrace Downs, Ngamara and Willowmere. What is appealing to me as a baker is discovering the nuances between flours and grains grown in different parts of the country. But would I be able to taste the difference?

Patrick Welzenbach, head baker at Daily Bread recently did a blind tasting of the same bread recipe made using flours sourced from different mills. The tasting revealed an ideal flavour profile for their signature bread made with flour from a specific varietal and origin. This type of benchmarking is essential to their growing business and potentially a very viable model for farmers to dedicate resources to growing for flavour and nutrition. The flour of our future would become less commodity driven and more artisanal, benefiting a wider community of arable farmers. What if this was the way the big mills operated, adding further value to our flour in terms of nutrition and much like during the pandemic lockdowns of this year, eaters were driven back to baking not only for enjoyment and necessity, but knowing that all our flour was as nutritious as it could be. Then the story being delivered would be one of true resilience, not only about securing our future for New Zealand grown flour but also for better health.

Patrick reiterates, “Daily Bread feels strongly about supporting NZ farmers who use organic, spray free and biodynamic farming techniques. Where possible, we source our wheat and rye from growers in the Canterbury Plains, which has an incredible climate for growing arable grains. When working with farmers, we mostly look for heritage grains and varieties that haven’t been manipulated.”

The flour I’m currently using is from Minchins Milling. I’d seen the name crop up and mentioned by other sourdough bakers in Instagram posts (@danthebakerdownunder; @thistable_moonlibby) so I was keen to do some research particularly into the nutritional qualities of the flour. Just after the first lockdown back in June, I started talking to Minchins Milling owner Martin Skurr whose family has been growing wheat on their Sheffield farm in North Canterbury for four generations. Riverview farm was established as a mixed cropping farm back in 1922 by Marty’s great grandfather Edward Skurr. Located on the south banks of the Waimakiriri River, “our climate and soil are perfectly suited to grain production. Cool winters combined with dry NW winds reduce the need for excess input to manage pests and disease.” This is Marty’s seventh year farming full-time. My order of the high grade stone-milled flour duly arrived and this is where I began experimenting and instantly noticed a difference in the elasticity of the dough due to the higher protein levels and quality. Standard NZ high grade flour is approximately 11.6% protein whereas the Minchin’s was up around 14%. Minchin’s main high grade variety is Conquest which has been generally regarded for many years as the best high grade wheat variety grown in New Zealand. “It has been in commercial production for 15 years, and to be honest is coming to the end of its life as a commercial variety,” reckons Marty. This is because it is becoming more susceptible to disease and lower yielding compared to newer varieties. “Our spray free variety is Sensas which originates from France”.

All the flour at Minchins is currently milled by the traditional stone milling method using an Osttiroller flour mill from Austria. Marty says, “This traditional method produces flour quite different to modern commercial roller mills. This is due to the grain being ground down to flour in one, sometimes two passes. In doing so it brings other parts of the grain not usually seen in modern flour into our flour. The result is a flour with more character, colour, flavour and possibly more nutritious.” This is the exciting part for me as a nutritionist. “What is the protein content? How much fibre is retained?”, I fired back in my email.

The fibre content of Minchins stone ground flour is more than double that of your typical high grade flour. Typical analysis puts it at 7.7% versus roller-milled flour at 3.5%. This tells me that a lot more of the bran is retained in the flour. The protein content of the spray-free flour is also higher at 12.6% vs roller-milled high grade flour at 11.5%. The stone ground high grade white flour I have been using has a protein content of 15.3% which accounts for its noticeably higher level of elasticity and extensibility even in my novice hands. I have also used their High Extraction high grade flour and am waiting on more nutritional information. The character of the flour, its colour and flavour, interests me as much as how the wheat is grown.

The story on Minchins Milling website is worth a read. The philosophy is simple: “we find the most sensible ways to use our land to yield the highest quality crops, whilst looking after the soil. Having a diverse crop rotation involving cereals, grasses, legumes and livestock are key to keeping the soil nourished and balanced. Nature working with us. Our aim is to reduce our carbon footprint whilst producing premium quality food.” Farming practices and technology that help to improve efficiency, resilience and biodiversity are the foundations that have been laid for the future. The farm includes 2ha of native wetlands which the successive generations of the Skurr family continue to care for.

Former Amano baker and now owner-operator or The Bread Project in Helensville, Dan Cruden is also a huge fan of Marty’s grain, knowing exactly where it’s sourced, down to the paddock that it was grown in. In Dan’s Instagram post he said, “With the partnership, we at The Real Bread Project not only support locals, but also help the farmer decide what wheat to grow that we then want to use to make our bread. Not only does Marty grow the grain, he also cleans and bags it. From there we can mill all our flour that is used in the bakery the day we make our bread. You can’t get fresher than that!”

It was this provenance story and discernment around the methods of farming and the relationship with the land that was becoming a common theme when I asked a series of questions of commercial bakers, small batch artisan bakers, chefs and sourdough enthusiasts: What are key considerations when choosing flour? Do you have a preference for using locally grown NZ wheat and why? Why do you care about sustainable farming practices, where there is also minimal use of herbicides and fungicides? Why are you interested in producing bread that’s more nutritious, easier to digest and perhaps overall better for gut health? Some of these questions are still to be answered but I was reassured that there was an emerging interest and strong shift amongst artisan and home bakers with a preference for local NZ grain, milling it themselves where possible to ensure freshness and the best organoleptic qualities in the bread they produced; and in nutrition.

Fraser McCarthy, chef and owner of Lillius is a fan of local flour, “I use Milmore Downs rye as it is consistent and organic, also because it’s from New Zealand. I make my own bread as it is a very therapeutic job and consisting of flour, salt and water only. There is nothing to hide when using naturally leavened bread. Getting it right all the time is a challenge! Health benefits are great from long fermented breads as the microbes process all the indigestible gluten that our body can’t. Making your own bread also cuts down on waste as you bake each day and can turn the leftovers into loads of other delicious things.” And that he does, into crumbs for coating the next day’s sourdough after the final shape, and bread soy and miso with incredible umami to brush over fish or pork collar.

Sam Forbes, head baker at Shelly Bay Baker, Wellington, has just changed the recipe for Shelly Bay Baker’s most popular sourdough loaf ‘the country rye’ to use 100% NZ organic stoneground flour. He is on a quest for the “tastiest, healthiest bread on the planet”. Having outgrown his earlier bakery, his new premises on Miramar includes a flour mill, a bakery and retail store. The grains that go through their milling operation Capital Millers is sourced from two NZ farms, Terrace Farm, Biogro and organic certified property near Methven; and the Conquest wheat from Ngamara organic farm in Rangitikei just two hours north of Wellington, belonging to Bruce and Suzy Rea.

Libby Moon, sourdough alchemist and baker, chooses the best local flour from farms with a strong ethos behind how they farm and maintain the health of the land. With a preference for organic, biodynamic flours for her beautiful crafted loaves. Flour with good protein levels, flavour and richness. Libby recommends sticking with the same flour for a while so that you can become familiar with the flour – how it feels, it’s texture, water absorption, the crust. Try it in all sorts of loaves to see how it responds.

At the recent Eat New Zealand Food Hui 2020, one of the panel sessions titled, “Local Grain Economy” spoke to “establishing a resilient and connected future for our grain growers, millers, bakers, chefs and eaters”. If you want to get into the technicalities of grain production there is plenty of reading on the Foundation for Arable Research NZ website. You can certainly geek out here. I did digress and had to stop myself going down another rabbit hole reading about nitrogen application for wheat and barley. Goes to show you can’t shake the scientist out of me.

The day immediately after the 2020 election, breadpolitics.com posted a piece titled The case for a regenerative organic farming network. The author, Isabel Pasch, is a science journalist and owner of the successful Bread & Butter Bakery. The call to action is clear: “By focussing on soil health, farmers can make more profit, grow healthier food, reverse environmental damage, mitigate climate change, strengthen communities and improve their own mental well-being.” It’s worth a read.

The case for a Regenerative Organic farming framework

Where you can purchase NZ grown and milled wheat flour:

minchinsmilling.co.nz North Canterbury

milmoredowns.co.nz North Canterbury

capitalmillers.co.nz freshly milled flour from Terrace Farm mid-Canterbury and Ngamara organic farm in Rangitikei

leftbankloaves.com – for Welly based readers, Wellington Sourdough online store for breads and organic stone ground flour.

Freshly Milled Zentrofan Stoneground Whole Flour

biograins.co.nz

References:

yara.co.nz/crop-nutrition/wheat/how-to-increase-wheat-protein-content-and-quality

nzplaces.nz/place/timaru-milling-company-building

flourinfo.co.nz

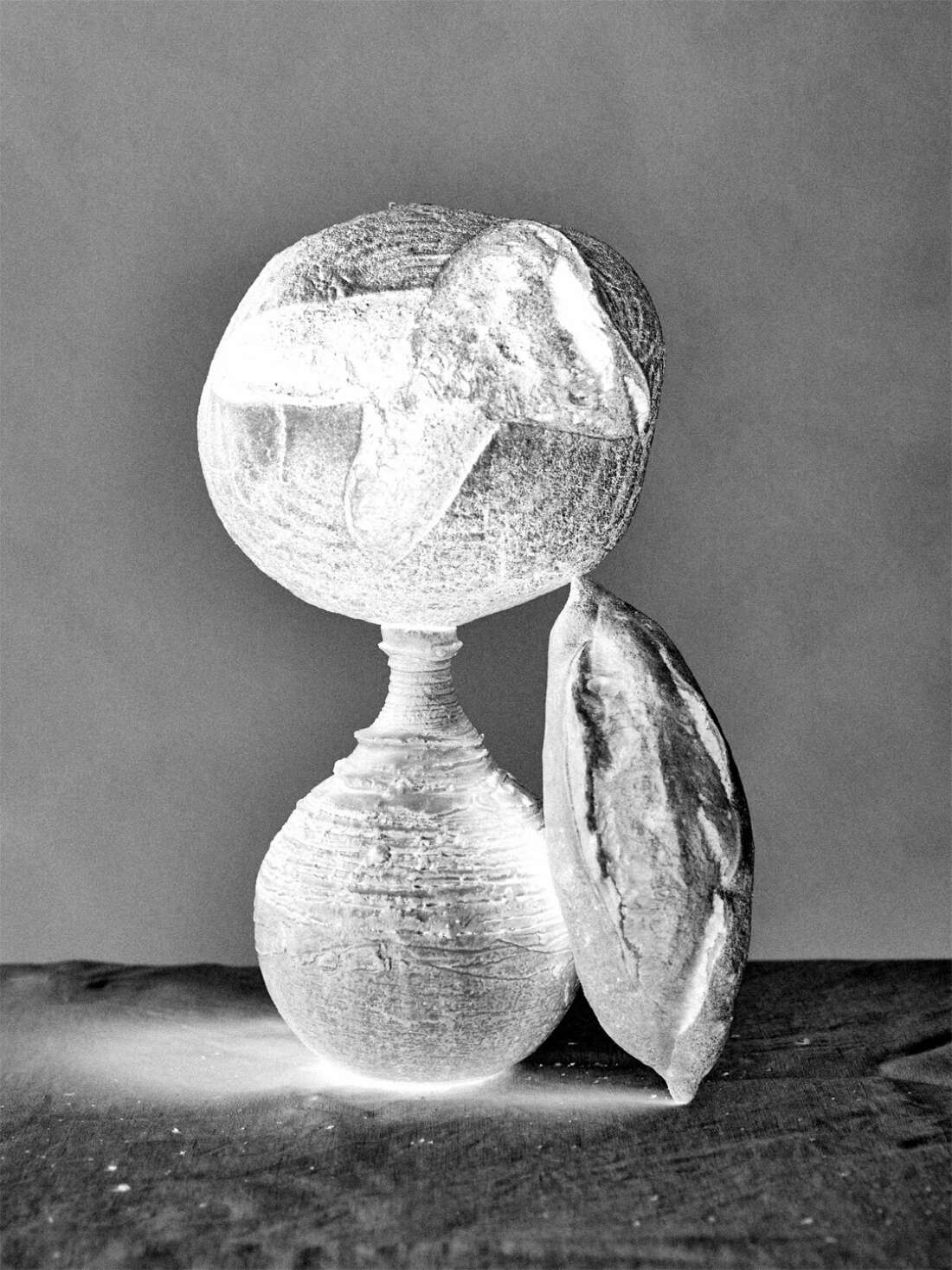

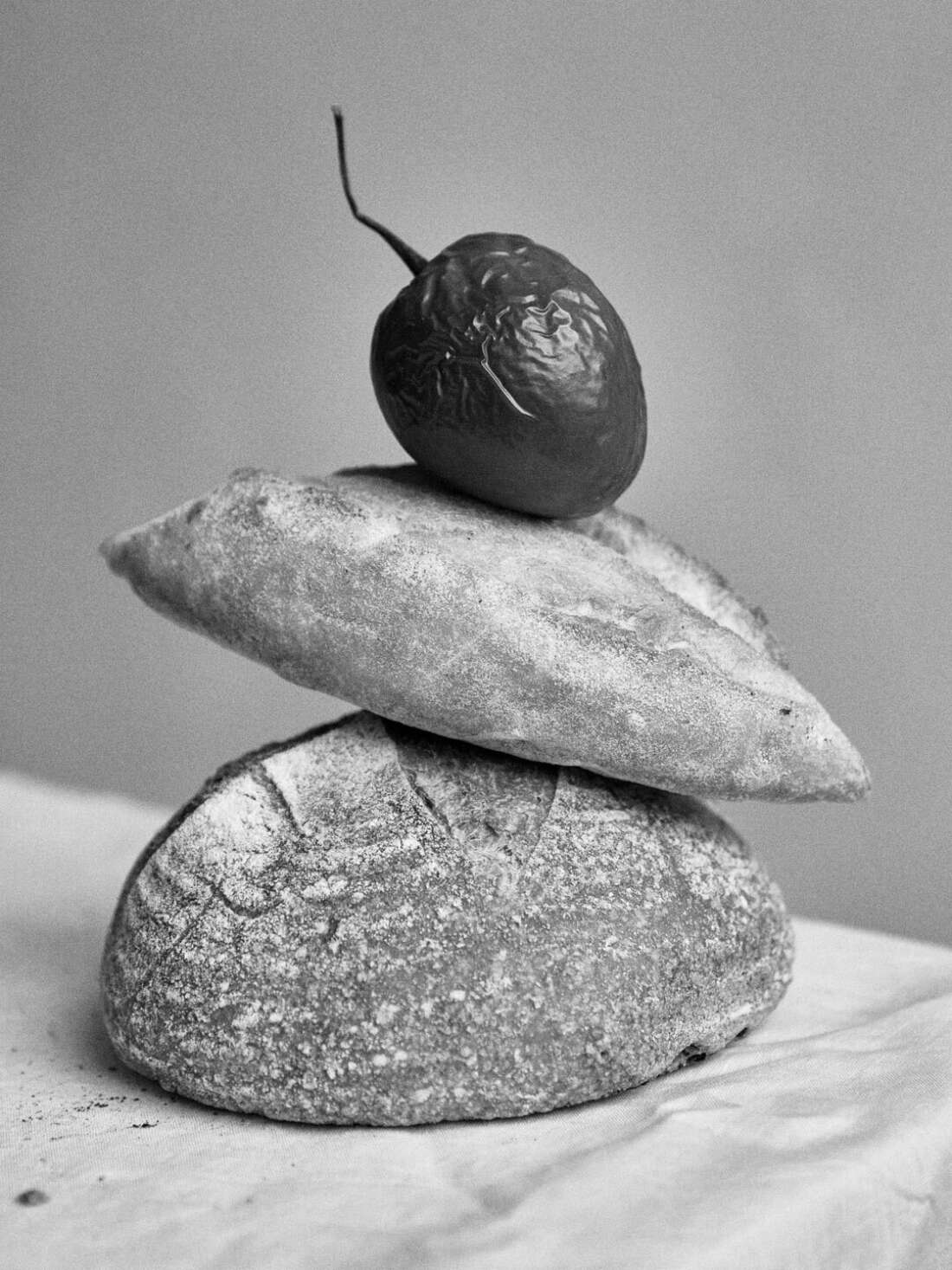

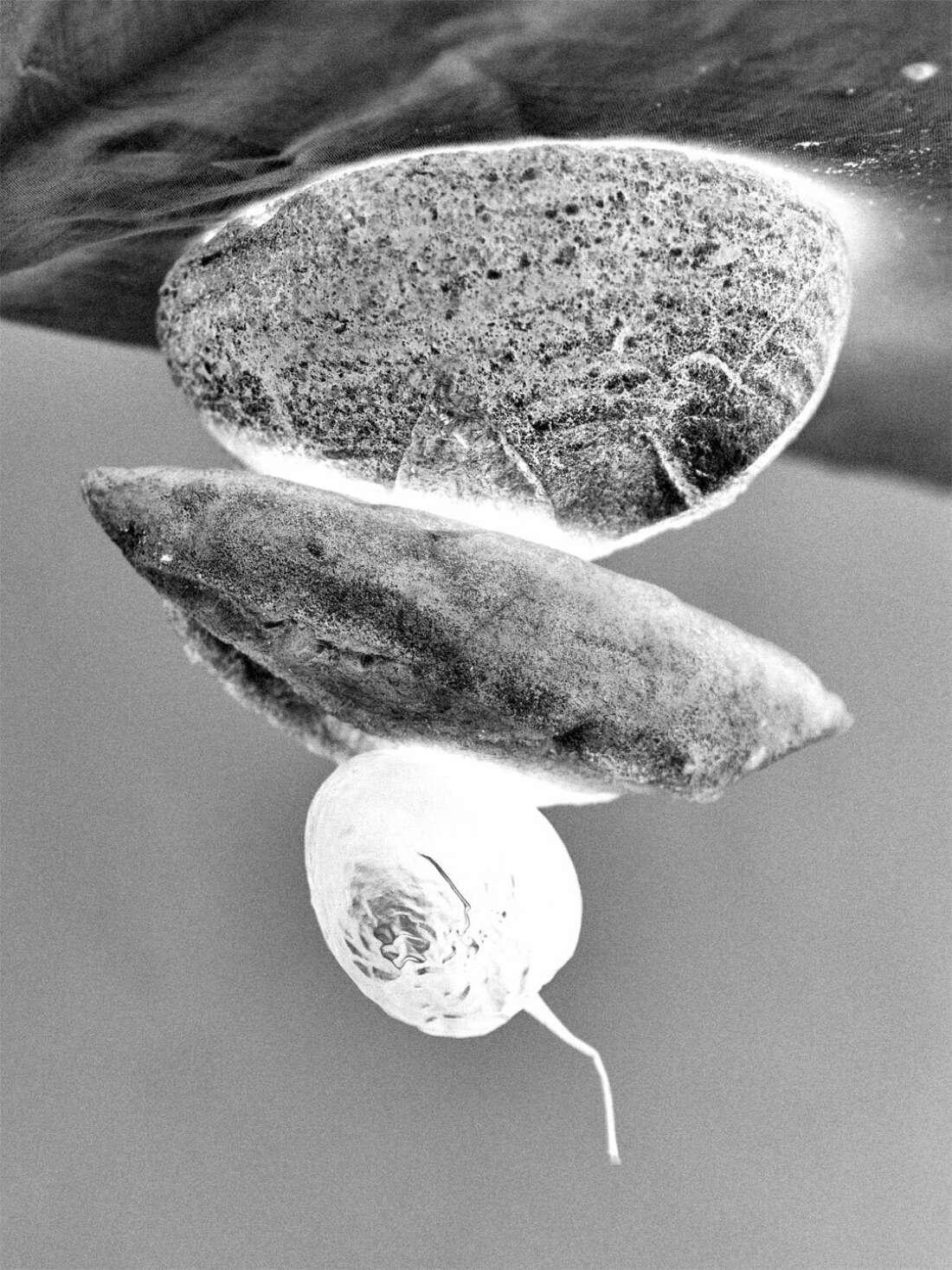

By Jennifer Yee Collinson. Photography: Charlie McKay. Set & Styling: Jess Murphy