Category — Travel

Compassion, coffee and community

One family’s journey into the heart of Mexico to help grow the world’s most delicious, disability-inclusive coffee.

“For us the biggest thing was building relationships, and it’s true that old saying, no one cares how much you know until they know how much you care”

In 2016 Jessica Pantoja-Sanders was called home: home to a country that ran through her veins but never under her feet. Having a Mexican father, Jess had always had a yearning to connect with her roots, the land, the people and the food. After years of making coffee in New Zealand, hosting Mexican cooking classes and dreams of perfecting a good Molé, the chance to live in Mexico arrived in the form of social enterprise — The Lucy Foundation.

The Lucy foundation was brought to life in 2014 by Dr Robbie Francis-Watene, a proud disabled woman pioneering disability rights across the world. The vision of the foundation is to empower people with disabilities and their communities, through ethical, economic and environmentally sustainable business. The opportunity arose to work with the coffee growing community of Pluma Hildago in Oaxaca, Mexico. With a growing market for ethical coffee in New Zealand, the coffee would be exported to Aotearoa with the entire value chain being disability inclusive, even the roasting. The Pluma project required field directors, so Jess, husband Ryan and children Lorenzo and Ebony moved to the small mountainous village known as the coffee Mecca of Mexico. It was the perfect recipe for Jess whose love of cooking, food and coffee were key ingredients in the transformative power of community.

Pluma coffee is a 200 year old heirloom variety cultivated by generations of coffee growing families on small farms. “In recent years, this highly valued varietal has come under threat from leaf rust and poor soil health,”explains Jess.Being a cloud forest region, the soil had been super rich in nutrients. However, following a hurricane and deforestation, to make room for coffee, the structure of the soil changed. Previously maintained by tree roots, the topsoil washed away. Families who in the past produced 100 sacks of coffee were now producing less than six per harvest. In an already fragile economic landscape, the threat to coffee was a threat to the Pluma way of life. This combined with a high prevalence of disability within the community, the plan was to work with coffee farming families living with disability to restore their coffee crops, add value with organic status, and offer employment opportunities in the process.

However, as important as the project vision was, the couple always knew it was going to be different when they got on the ground. “You can always have these ambitious dreams and goals but what was important to us was that we weren’t going to go in there with a saviour mentality,” stresses Jess. It was for this reason The Lucy Foundation was set up as a social enterprise. The organisation would work alongside the community initially and empower the community to eventually take full ownership of the project.

After arriving in Mexico, the family spent three weeks in a nearby town an hour and a half away from the village. It became obvious that they had to find a home in Pluma. “We needed to be there 100 per cent. To be seen driving out of the town you could feel the locals thinking, ‘oh they’re not really here for us.’ We wanted to have a relationship where we lived with the people we were working with on a day-to-day basis, that they got to see us, our good, our bad and all of the in between. It was important we shared those experiences with them as well,” explains Jess.

The first few months were difficult. Other than the families they worked with, it felt like the community kept their distance. “There have been so many projects there that have done more harm than good, for a long-time it was just staring and, ‘why are you here?’ questions.” But once the family started working with five coffee growing families, all with at least one disabled member, the community saw they were there for good. “Our neighbours became like family, they spread the word that we were the good guys,” Ryan chuckles. Having locals that were well respected in the community vouch for them was their initiation. “It’s the way it works there, and you can see why, after generations of heart aches, there’s a lot of history there. It can be a very hard life, and in the past a lot of foreigners had come in to do their best to help but did more damage than good,” laments Ryan. “I think some cultures deal with that differently, and I think this was a culture that had toughened their outer shell, and understandably,” Jess adds.

Moving the whole family over was important for Jess and Ryan, to show their children love in action and establishing a connection to their heritage. “For us the biggest thing was building relationships, and it’s true that old saying, no one cares how much you know until they know how much you care,” says Ryan. “Just the fact that we lived there and had our kids there was huge. The kids were amazing for networking and breaking down walls. Kids don’t care, they just want to play. Our son’s name, Lorenzo, is such a Mexican name even though he’s mostly a ‘whero’,” laughs Jess.

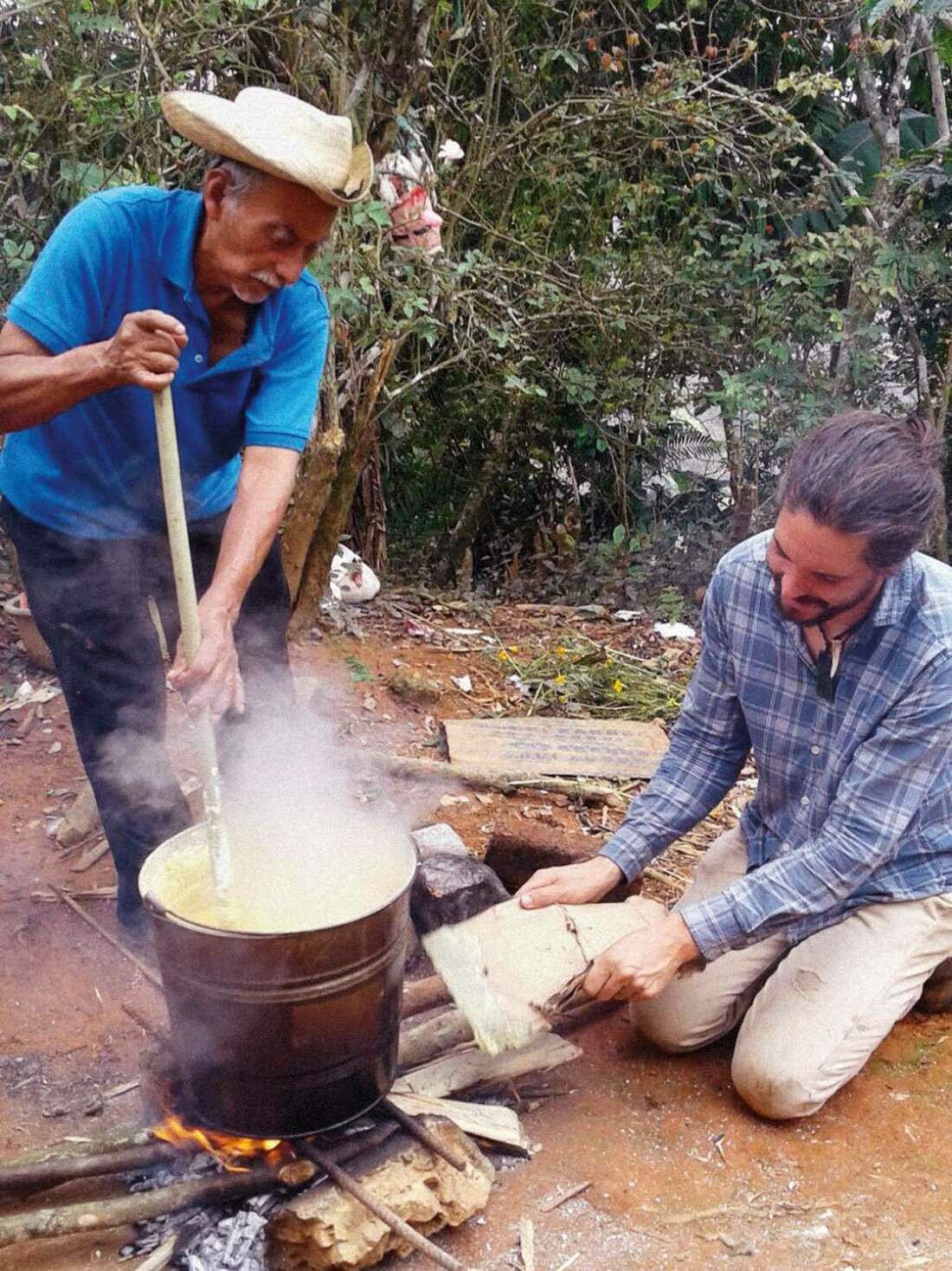

As the family settled into their new way of life, community needs were identified. Accessible agricultural workshops as well as disability-specific workshops around wellbeing were set up. These were opportunities for both abled and disabled people to interact in a meaningful way, while contributing to a shared community goal. Workshops, held by Mexican organic farming experts, included: making bio-fertiliser, harvesting microorganisms, cultivating them and reintroducing them into the soil, and making big ‘soups’ made with local soil fungus, milk and cow manure. This rich brew was diluted down and added to the soil and sold to surrounding farms. Key to these regenerative practices was helping the families understand the value of farming better and organically and with a rare varietal getting a higher price and yield. The foundation then purchases the coffee off the farmers with members of the community, including those with disabilities, processing the beans. Hand selection ensures higher quality, a premium product and employment. Last season the community exported 60 kilograms of coffee: this year it’s over 400.

Larger farm owners saw the work the project was doing and asked for workshops on their farms. Ryan would bring the team along and those with disabilities would assist Ryan with the workshops. “People started seeing them involved with The Lucy Foundation, coming to farms and being a part of what we do, we started noticing a huge shift. Brothers Erminio and Juan were no longer being bullied, rather included,” smiles Jess.

Life can be hard in Pluma even as an able-bodied family member. “Just having enough to survive can be a challenge. When not everyone is contributing there can be underlying resentment, they get pushed aside and neglected. For these guys to bring value to their family, to be able to contribute, it brought a huge sense of self-worth and their families started seeing them as a valued part of the family,” says Ryan.

Soon Jess was learning how to make everything from salsa de chicatana (salsa made with ants) to pozole with her neighbour, Gabriela Hernandez or ‘Mama Gaby’. Mama Gaby and husband ‘Papa’ Pablo became like parents for Jess and Ryan. Their daughters, Marisol, Yazz and Luli became like sisters and their son Pepé like a brother. Alongside the project the couple saw other ways to help their Pluma family. “We had the project stuff there but we had people in New Zealand who wanted to help in other ways. When there was a need we would put a shout out to our Kiwi community and people would put their hands up.” One such need arose with Pepé. Deprived of oxygen when he was born, he went to school until second grade before being told not to come back and that he would never be able to read or write. A community café back in New Zealand used their profits to purchase reading curriculum in Spanish which was sent down from America for Pepé. Leslie — a local organic farmer, friend of the foundation and a doctorate in reading recovery — then taught Pepé how to read and write. Now every morning at 8:30, Pepé meets with her to continue learning. “He has flourished in so many ways, he’s excited, and now it’s always, ‘can I read to you? I need to practice!’ ”says Jess.

Or there’s Erminio who never spoke. After two years of doing woodwork classes with Ryan he asked how Ryan’s day was. “He started smiling, his physical appearance changed, his head was high, there were handshakes, eye contact and helping with cooking. He loves using the drill, hammers and skill-saw now,” Ryan explains with joy. “It’s a beautiful thing to see people who were once invisible see their worth, their inherent value and witness the physical, social and emotional changes. Even those few words were wonderful to hear,” remarks Jess.

Jess also perfected her Molé dish with the expert help of Mama Gaby. “You read about how Mole takes 18 hours to cook, but really, half of it is walking to find the ingredients! The chillies need roasting and soaking, and then you meet people while you’re foraging and walking down to the mill to grind them all up,” grins Jess. “When you cook in Mexico you are 100 percent involved in your cooking, you don’t chuck it in the oven and leave, your oven is used to store Tupperware and your stove top is used to do everything else.”

Jess is passionate about people truly knowing what’s on their plate. “In the West, people can be so disconnected from their food, the farmer, the process, the way things really taste and smell,” she laments. “Today, life is full, and you have to have things that work for you, but we are missing this fundamental part of cooking and eating together.”

The conditioning of individualisation in the West became a stark contrast to the Mexican way of life for the family. “It’s not the way it worked there, and it changed us, it was beautiful,” says Jess. “People don’t hold time like they do here, it’s actually a good thing,” explains Ryan. “If someone comes to your house that becomes your priority, it doesn’t matter if you were on your way out and locking the door instead you say, ‘come in, let me make you a drink, let me feed you, what’s new?’ You make time for people, it’s a blessing one way or another.”

“You always had hot chocolate ready to offer, always had bread to give. Realising you don’t have to be presentable for people to want to enter your world, the way you are is enough. So many nights, knock, knock, knock, and we would open our door,” Jess reminisces.

“Food was it. Coffee and food. That’s the way to build relationships. The culture is one of the most passionate and hospitable in the world and I feel like we learnt a lot more from them than we were ever able to impart to them.”

After two and a half years in Pluma, the Sanders family returned to New Zealand with more than their hearts full. The project had lift off and their work, for now, was done. “It doesn’t matter how integrated you are into a community, it’s never going to be as successful until locals take ownership. As amazing as it was for us to be there, it didn’t take off until locals took it over. It’s exciting for us to see that they realised their agency and that we wanted to continue to help people in New Zealand with disabilities too. They saw their place within the whole value chain, and realised how important it was to keep going.”

“Un ideal, hacer qué algo hermoso qué no existía por mi”

Our ideal should be to create something beautiful that did not exist before us.

-Zapotec proverb