Category — Features

Che Guevara, Chez Panisse

Why are the politics of the alternative food movement in wealthy countries so underwhelming?

By Adam Calo

Some of the most powerful anti-capitalist logics, imaginaries,

and social projects owe their origins in food. Nothing could be more

core to concerns over the means of production than produce

itself. Control over the basis for social reproduction offers a power of

self-determination that confronts the disciplinary force of the wage

relation. That is why concepts like food sovereignty, agroecology, and

re-peasantization have seized the imagination of post-capitalist

movements worldwide. Some, argue a transition out of capitalism necessitates an agriculture that is subsumed under the logics of ecology instead of the market.

At the same time, nothing could be more underwhelming than the politics of

“good food” in wealthy nations. In places like the US and Europe, the

radical promise of a post-capitalist food system tends to be watered

down into elite-to-elite production and consumption circuits. Such

production relations are embodied by a-political and technocratic

farming typologies like farm-to table restaurants, regenerative

agriculture, eco certifications, and nature based-solutions. Or, as

Julie Guthman calls it, “yuppie chow.” 1

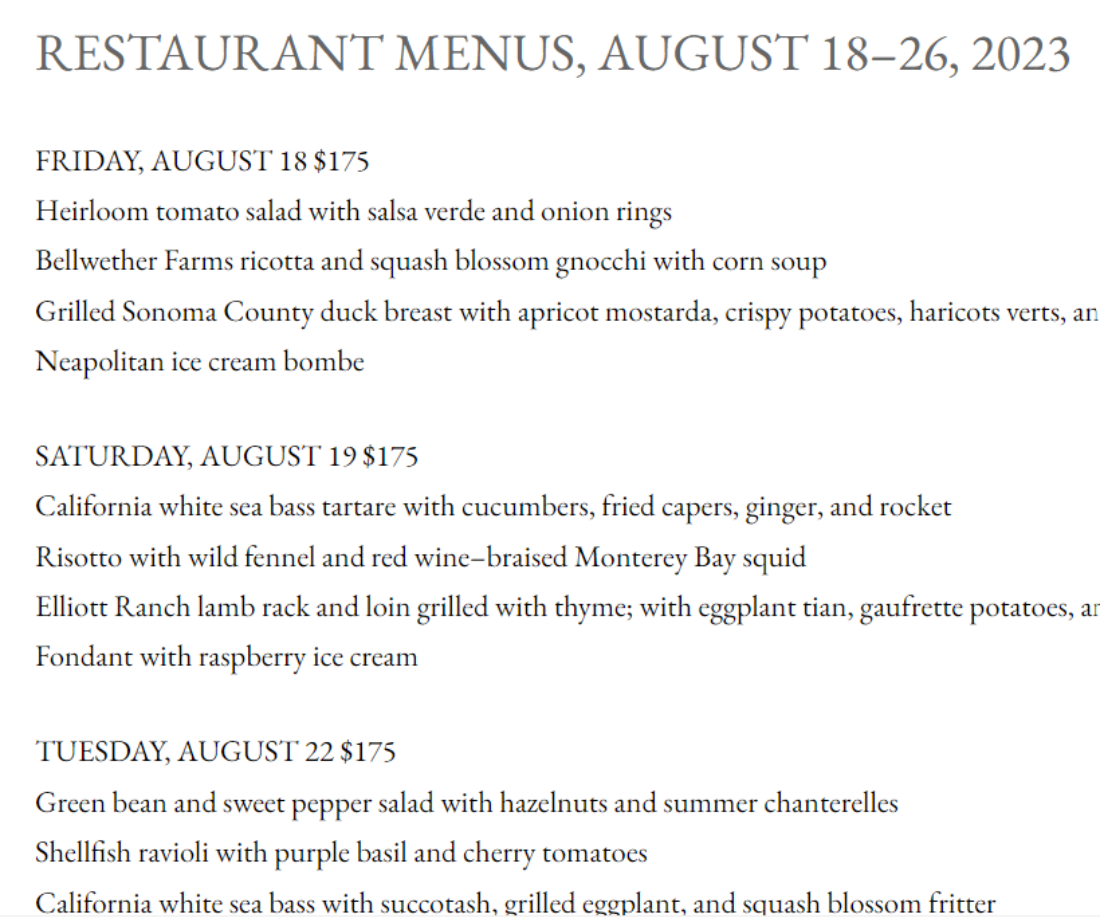

The flag bearer for this type phenomena of farm-to-table consumption as

social change might be Alice Waters, founder of the slow food and

restaurant Chez Panisse in Berkeley California.

Waters, more than a talented chef, expounds extensively on issues of

food system politics. Through these writings, the self-satisfied

politics of good food comes to the fore. In a recent book, We are What we Eat, A Slow Food Manifesto Waters writes:

"The ultimate stewardship we can practice in the restaurant is feeding people delicious food that’s good for them, and that has been grown in a way that considers the environment. I couldn’t imagine running a restaurant where you’re not thinking about that as your primary motivation, especially in the face of climate change. When you’re feeding people in the right way, I think they digest stewardship almost subliminally. I’ve seen it happen again and again. They feel cared for, they feel connected, and because it tastes so good, they feel inspired to cook that way in their own homes."

For Waters and her many imitators (Blue Hill comes to mind), a politics of stewardship

suggests that the problem of the food system is one of weak morality. Weakness of vision amongst farmers and of eaters is preventing better

land management and nutrition decisions from being made. On the

contrary, those who have clear vision of regenerative practices, possess

the legitimacy to govern the land.

Feeding people “the right way" ( $175 a meal?), or rather educating them through food is central to the Chez Panisse theory of change. Here, highly mobile and entrepreneurial farm owners sell at premium prices to highly mobile and entrepreneurial business

owners who sell to the most niche of the niche. The “we” in We Are What We Eat is highly problematic.

It’s no doubt that some of the farms that supply the restaurants of the good food establishment

are strongholds of diversified farming practices. It’s also true that

Water’s has explored possibilities of expanding a model of elevated

gastronomy to public schools.

But to think that this model can serve broad ecological regeneration

for the land and quality nutrition for all kinds of eaters is naïve at

best and mendacious at worst.

This is an argument that says through a revolution of taste, individual households will cook better

in their lives, assert their power of consumers and ostensibly challenge

the industrial food system’s force-feeding of cheap flavorless

calories. May a thousand tasting menus bloom, I guess.

Thankfully, decades of scholarly attention has laboriously critiqued this theory of change and found it lacking 2345. After such critical appraisal of the so-called “good food movement,” it’s clear that something rotten at the core of most alternative food projects inhibits their post-capitalist potential. What scholars don’t agree on is why these politics persist, if the good food crowd can ever become more politically engaged, and what it might take to spur this change.

It all comes back to land

I argue that the hidden force that dilutes the transformative capacity of radical food projects is the land beneath them. Entrenched exclusionary land relations discipline life in liberal

sovereign states. These norms emit an obscured force that molds agriculture to the logics of a narrow, yet powerful conception of

property. Trying to practice radical food without a politics of reimagined land relations places alternative food production at the mercy of the property regime.

Unable to reimagine or contest hegemonic land relations, alternative food

imaginaries in the capitalist heartlands have taken a pernicious form of

neo-Chayanovian escapism. In this version of alternative food, the

nature of property is not a problem. What’s wrong is that property isn’t

evenly distributed to smallholders that would otherwise be able to use

their productive forces to produce food sustainably. This idea leverages

the power of private property as the main tool to gain the required

agency to produce food without the hooks of the unregulated market. Stewardship and exclusion go hand in hand.

Thus, the bastions of agroecological production and solidarity economies in

the global North are found to be practiced on private property of

exclusionary value. This is the story of The Biggest Little Farm, Barbara Kingsolver’s Animal Vegetable Miracle, and Joel Salatin’s Polyface Farms—all cases of devoted land managers whose story of agroecological triumph only begins after securing

or inheriting multi-million dollar properties. Absent a radical

politics of transformation, advocates of this agrarian populist vision

see the only feasible path forward as a retreat to the countryside and

self-sufficiency.

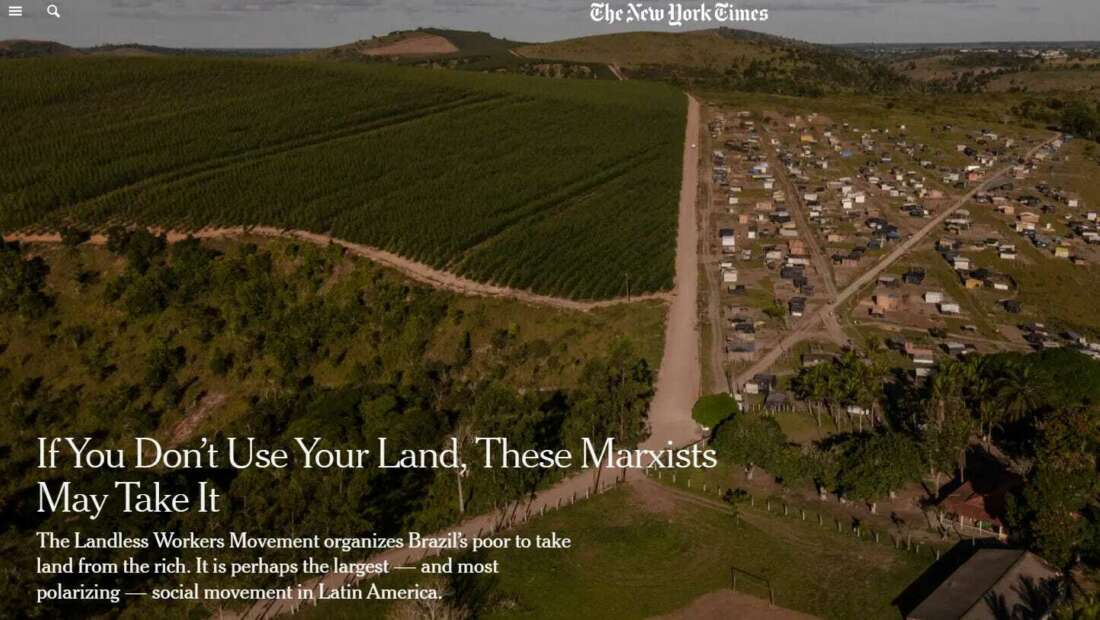

Compared to the use of agroecology as a method in struggles of liberation amongst social movements like La Via Campesina and the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST — Landless

Workers Movement), the permaculture farms, and holistic grazing

exemplars succumb, I think, to the critique of hobby farming. The MST,

with their legal sophistication, distribution to the hungry, and

politics of occupation strikes fear into the New York Times world

politics section.

In contrast, the second career heroes of The Biggest Little Farm ruffle no feathers and draws a praising monochromatic review in the film section.

The food movements of the Global South strike class conscious notes of Che

Guevara, while their counterparts in the Global North harmonize with Chez Panisse.

Centering the land question within food movements

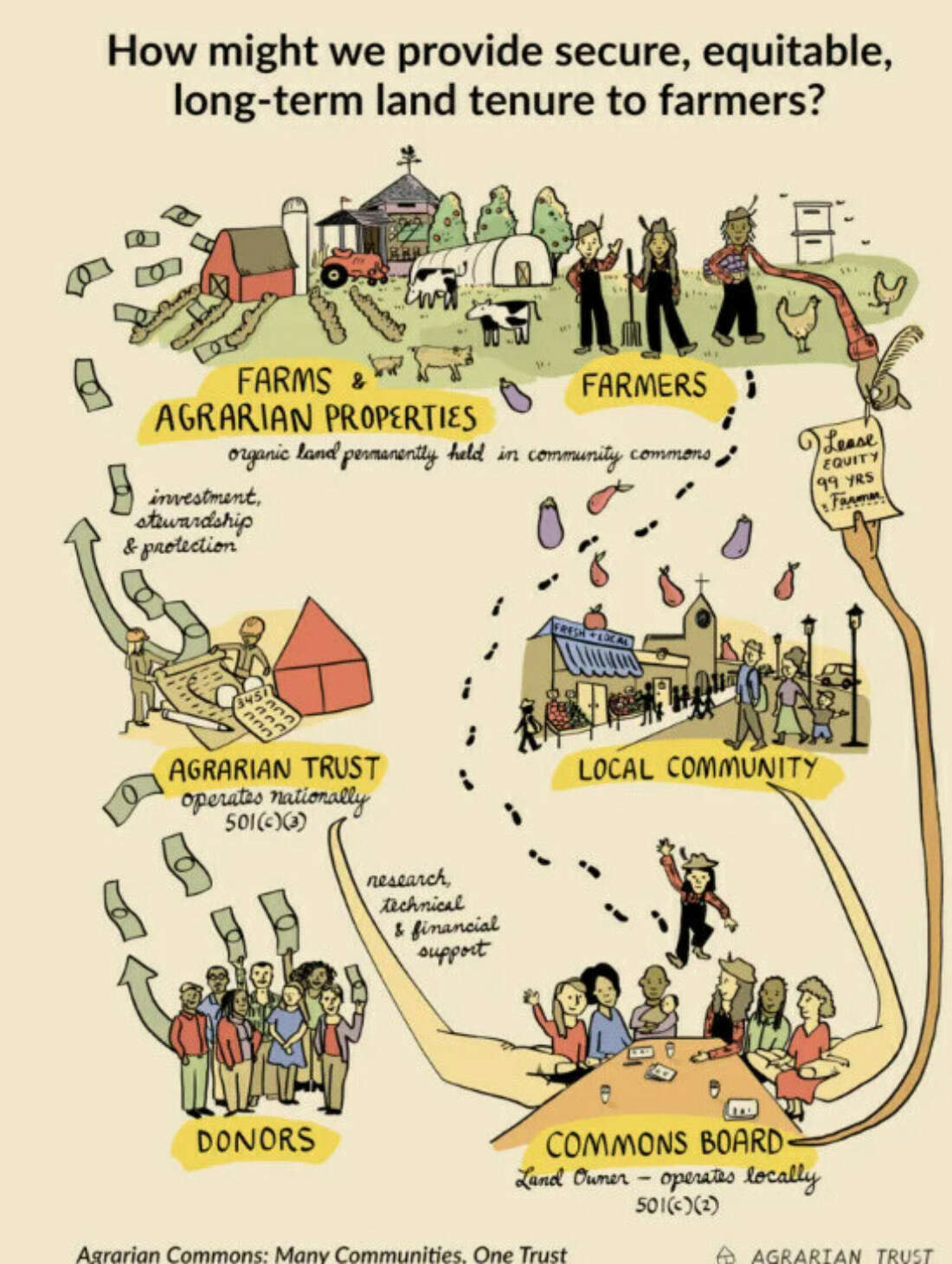

Recently, however, some actors traditionally associated with the neo-Chayanovian model have become perhaps reluctantly engaged with new innovations around land access, use, and control. A small wave of ‘food commons’ projects have launched farmland acquisition and redistribution efforts that force renewed thinking about the limits to projects of ‘good food’ in the Global North. These projects aim to acquire control of food production and distribution via collective land and asset ownership and then implement experimental governance and tenure systems. These experiments may offer distinct logics of production, ownership, and meaning of landscape. Such a combination of “peasant economy” logics mixed with pursuit of legal remedy to prevent capitalist penetration may begin to realize the deeper promise of the Chayanovian non-capitalist form of production.

Groups like Minnow focus on legal remedies for land rematriation in part through renegotiating unsettled tribal disputes. Kapitaloceen raises funds to purchase land, then attempts to decommodify it forever. Terre de Liens,

perhaps the original model, purchases land with public investment, then

installs agroecological farmers with secure leases. The Agrarian Commons creates new legal structures of food governance, after having purchased the land with a mix of public and private capital.

All of these experiments show an attempt at threading the needle between

strong property entitlements and the demands of agroecological

production. Compared to the farm-to-table/ farmers market model which

entrenches current patterns of unequal land ownership, these food

projects are evidence that a new way of thinking about land is required

to deliver a more transformative food politics. It is unclear if these

models will only serve as islands of production insulated from

capitalist logics or if absent a greater transformation to the legal

entitlements of property, they may ultimately be warped by forces of

“impersonal domination”. These types of legal experimentations and

loophole seeking may be a far cry from land occupations that form the

basis of many social movements. But they may offer a replicable

intermediate strategy for geographies hostile to going beyond deeply

held notions of property.

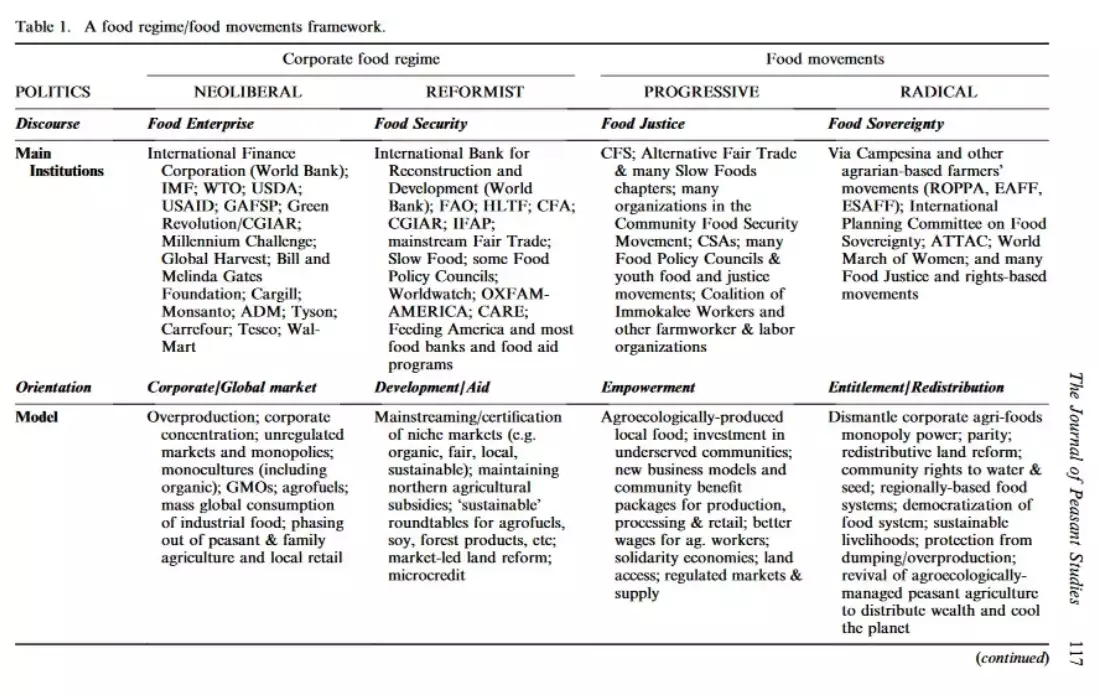

In Holt Giménez and Shattuck’s perennially useful framework for assessing food system interventions, they describe a typology of potential responses to ongoing food crises.

They suggest responses to the environmental and social problems

of the food system manifests as as a continuum consisting of

neoliberal, reformist, progressive and radical politics. They suggest

that the dominant responses to food crises has been a retrenchment of

neoliberal and reformist approaches like food aid, climate smart

agriculture, corporate responsibility, and new eco certifications. Using

this framework, the Chez Panisse politics of good

food and land stewardship straddles the progressive and reformist

tendencies and will not lead to transformation of the food system.

It was disheartening to read that Mark Bittman, a foodie who has dipped a

toe into more radical food politics—even calling for land reform in the

US—has announced his swansong: A new restaurant 6.

In Shattuck’s conclusion, the authors suggest that new coalitions between

progressive and radical actors are what might shake the foundations of

the food system towards something more socially just and ecologically

sensitive. Centering land in questions of food politics forces questions

of power, wealth, the law, and injustice to the fore. Here, the land

question may provoke a shift amongst actors in the progressive camp

towards a more transformative food politics.

Dr Adam Calo is Assistant Professor of Environmental Governance and Politics in the Geography, Planning and Environment group at Radboud University in the Netherlands. Building the bridge between land reform and food systems change.

This article is Published with his permission and first appeared on his substack, you can view his website here, and listen to his podcast Landscapes here.

1 Of course, there are radical elements of the food movement in wealthy

nations. Abolitionist food projects, land back and land re-matriation

projects and a smattering of land occupations for food production show

that radical politics are possible, but often not associated with the

mainstream of food politics. As DeLind puts it, we’ve hitched the food

movement wagon to the wrong stars.

2 Guthman, J. (2007). Can't stomach it: How Michael Pollan et al. made me want to eat Cheetos. Gastronomica, 7(3), 75-79.

3 DeLind, L. B. (2011). Are local food and the local food movement taking us

where we want to go? Or are we hitching our wagons to the wrong stars?. Agriculture and human values, 28, 273-283.

4 Alkon, A. H., & Agyeman, J. (Eds.). (2011). Cultivating food justice: Race, class, and sustainability. MIT press.

5 Guthman, J. (2008). Bringing good food to others: Investigating the subjects of alternative food practice. Cultural geographies, 15(4), 431-447.

6 It’s not to say that delicious restaurants can’t play a role in a

transformed food system. Perhaps that is what Bittman is trying to

prove. But a restaurant focused food system intervention demands scrutiny with regards to how it engages with the land question.